Enter the most secure building in Corning, N.Y., and there it is: the birthplace of a material you touch hundreds of times a day.

That’s because it’s where they design, tweak, and then casually beat the hell out of the glass that adorns today’s phones until it either breaks or proves itself worthy of gracing a flagship device. The video of engineers melting sand into optically flat sheets before putting them through industrial-scale punishment is a rare glimpse into why modern phones hold up under concrete, keys, and everyday chaos as well as they do.

- From 1,650°C to in‑air perfection in the Fusion process

- The science of toughness: compressive stress in glass

- Scratch tests that resemble real life device wear

- When scratches become cracks under localized pressure

- Drops On The Pavement Without Stepping Outside

- Why this lab matters for phones and materials science

Corning’s Gorilla Glass has become an invisible standard throughout the industry, found on billions of devices, according to the company.

But the R&D heart of that success is still famously closed. Inside, I witnessed the birth of glass in airborne perfection and the reason why the test racks look like a gym for materials — everything lifted, slammed, flexed, and scratched with clinical precision.

From 1,650°C to in‑air perfection in the Fusion process

The sequence starts in a furnace, at about 1,650°C — hot enough to be brighter than magma. Engineers feed a closely controlled recipe — silica plus proprietary modifiers — into the melt and steer it into a V-shaped channel known as an isopipe. The molten glass then flows over the sides and rejoins at the bottom to create a single ribbon, which cools as it hangs in open air.

It is this “Fusion” process that is the silent marvel of smartphone glass. Since the sheet hardens without contacting rolls or molds, its surfaces come out atomically smooth, with no mechanical abrasion to be polished away. That unblemished finish is the source of strength long before any chemical enhancement comes into play.

The science of toughness: compressive stress in glass

Once formed, the glass undergoes ion exchange — smaller ions on its surface are traded for larger ones in a hot salt bath. The resulting compressive layer clings to the surface like a tightening belt and halts cracks from spreading. Materials scientists have understood this for decades; it’s a textbook example of compressive stress overpowering the tensile forces that want to turn a scratch into a fracture, and it is reflected in work from institutions like NIST and ASM International.

Engineers here say less than you might suppose about buzzwords, and more so about flaw control. A stable, thick compression layer with ultra-smooth surfaces is what prevents micro-damage from spreading into a spiderweb of heartbreak. That’s the distinction between a scuff that you can overlook and a screen cracked beyond repair.

Scratch tests that resemble real life device wear

To quantify abrasion, the lab’s “Scratchbot” tows graded sandpapers across samples at known loads. In a demo of the test, one rival aluminosilicate panel acquired a visible scar at 1 kg. The rival panel cracked clean in two at the same weight, while a Gorilla Armor panel (the same drink-of-water blend on some premium phones today) still shrugged off 4 kg unscathed. Keys vs. plastic vs. glass demos are supposed to remind you: hardness and surface finish count.

Then there’s the purse-and-backpack simulator. For minutes, a glass coupon tumbles inside a sealed cylinder with coins, a nail file, and other pocket gremlins. It doesn’t sound exciting, but the randomized collisions mimic the continuing low-level abuse that destroys most surfaces over months. The point is not theater; it’s statistically representative harm.

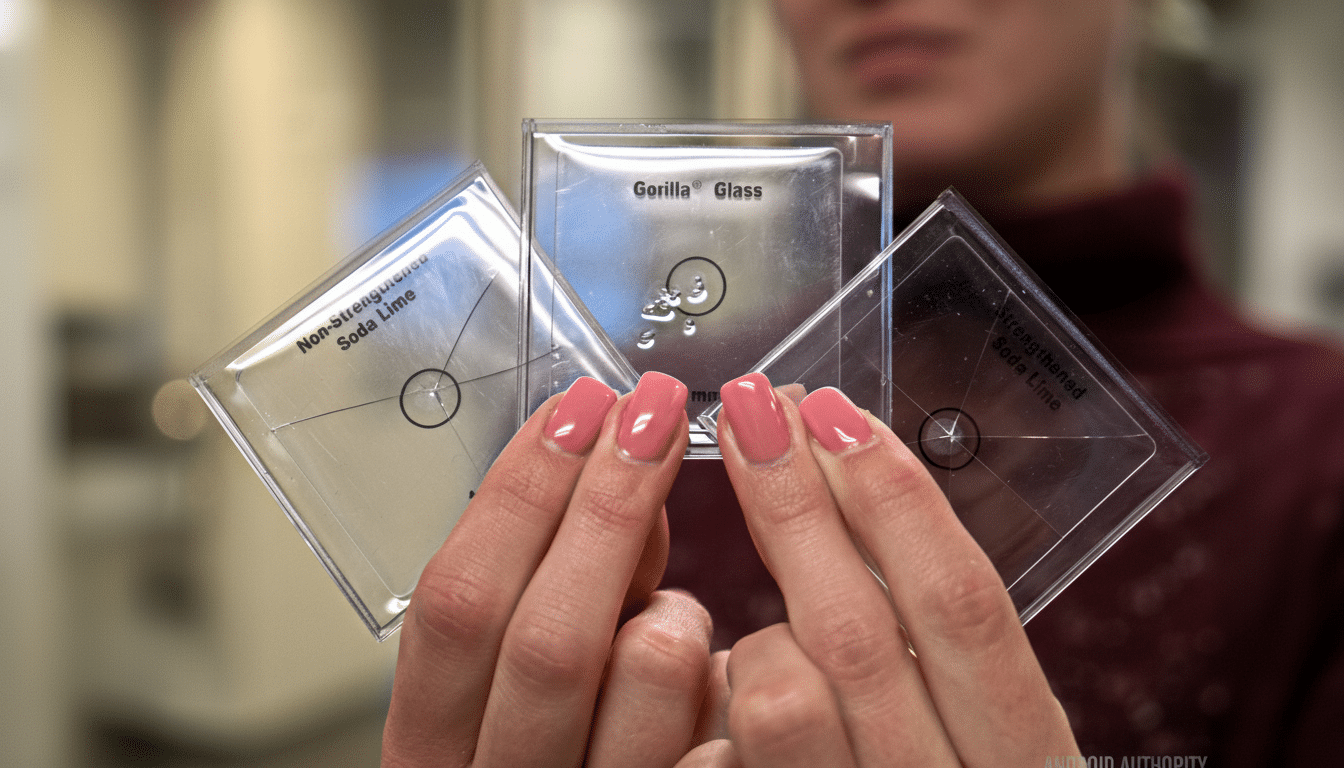

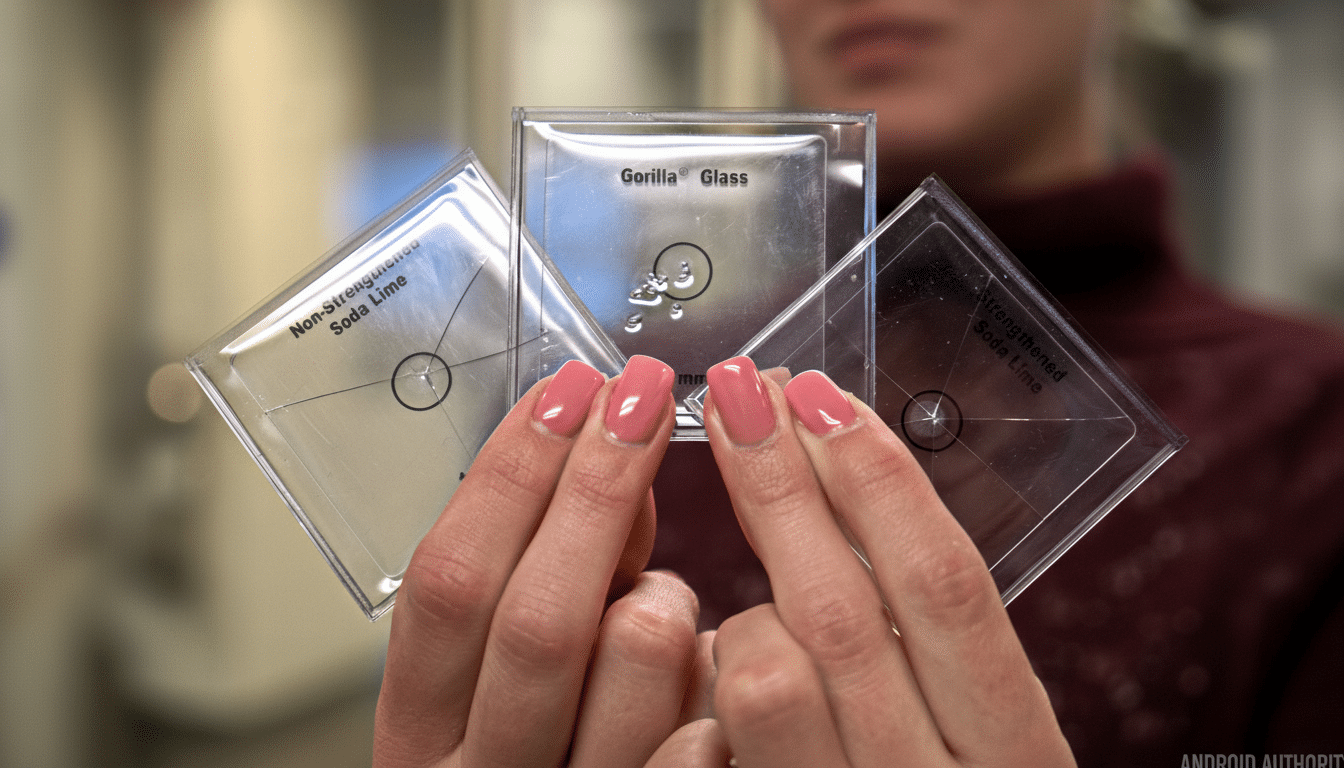

When scratches become cracks under localized pressure

The “pen push” test shows the brutal consequence of failures. An identical micro-defect is introduced by engineers into three equally thin samples: conventional soda-lime, chemically strengthened soda-lime, Gorilla Glass. Pressing with a blunt stylus, the first pops at not too great a pressure, then the second at increased load. For much longer — occasionally to the point where the operator strains with both hands — that Gorilla panel endures, for the reason that the compressive surface layer prevents the crack from opening.

This phenomenon is described in fracture mechanics textbooks as crack-tip shielding. In the lab, it seems almost magic until you start to sense all that force under your palms, with the pane still refusing to let go.

Drops On The Pavement Without Stepping Outside

Impact is a different beast. Corning’s “Slapper” is a more punky device, bending and snapping curved sheets hard against sandpaper-studded steel to simulate asphalt. A non-Gorilla control shatters on impact; the Gorilla one weathers blows from bigger fixtures, including a towering “mega slapper.” Repeatability of conditions is the point — speed, curvature, and surface roughness are all standardized.

With controlled device-level studies, a drop tower releases weighted phone “pucks” onto surfaces from granite and stainless steel to real street asphalt while high-speed cameras capture flex, rebound, and crack initiation. That footage informs design tweaks to thickness, curvature, and edge treatments that handset makers can actually use.

Why this lab matters for phones and materials science

The Corning campus is a spread-out place — thousands of employees, hundreds of labs, and a history that reaches from Edison bulbs to the fiber that carries the internet. Company archives and industry reports have credited Corning glass in early TV tubes, as well as Space Shuttle windows, and billions of kilometers of optical fiber laid out across the globe. That heritage is evident in the culture: every test serves a purpose that’s grounded in field data from real customers.

No glass is unbreakable. But when you stand in this lab and see materials getting pushed until they give out, it makes a little more sense how the odds of survival just keep going up. So the next time your phone bounces on a slab of concrete and comes away with just a scuff, it’s because somewhere in upstate New York, that same panel was tortured into being better.