Google once floated the idea of taxing power-intensive background behaviors on Android by literally forcing apps to pay for the power they consume. The so-called Android Resource Economy, which was scrapped before it got out of the experimental phase, treated battery as a rare and valuable resource, requiring apps to spend actual money to perform background tasks. The idea of Google taxing background work raises important questions not just about the company’s willingness to enforce its Terms of Service but about the broader practice of what Google believes it has a right to enforce. These are particularly relevant concerns for a platform that is functionally the only service, because unlike the web, it can decide what gets run directly. The approach called for making apps pay a fee in battery life, rather than a fine, and then giving platform operators what’s essentially a “legislated” right to cap an app’s access to its own battery.

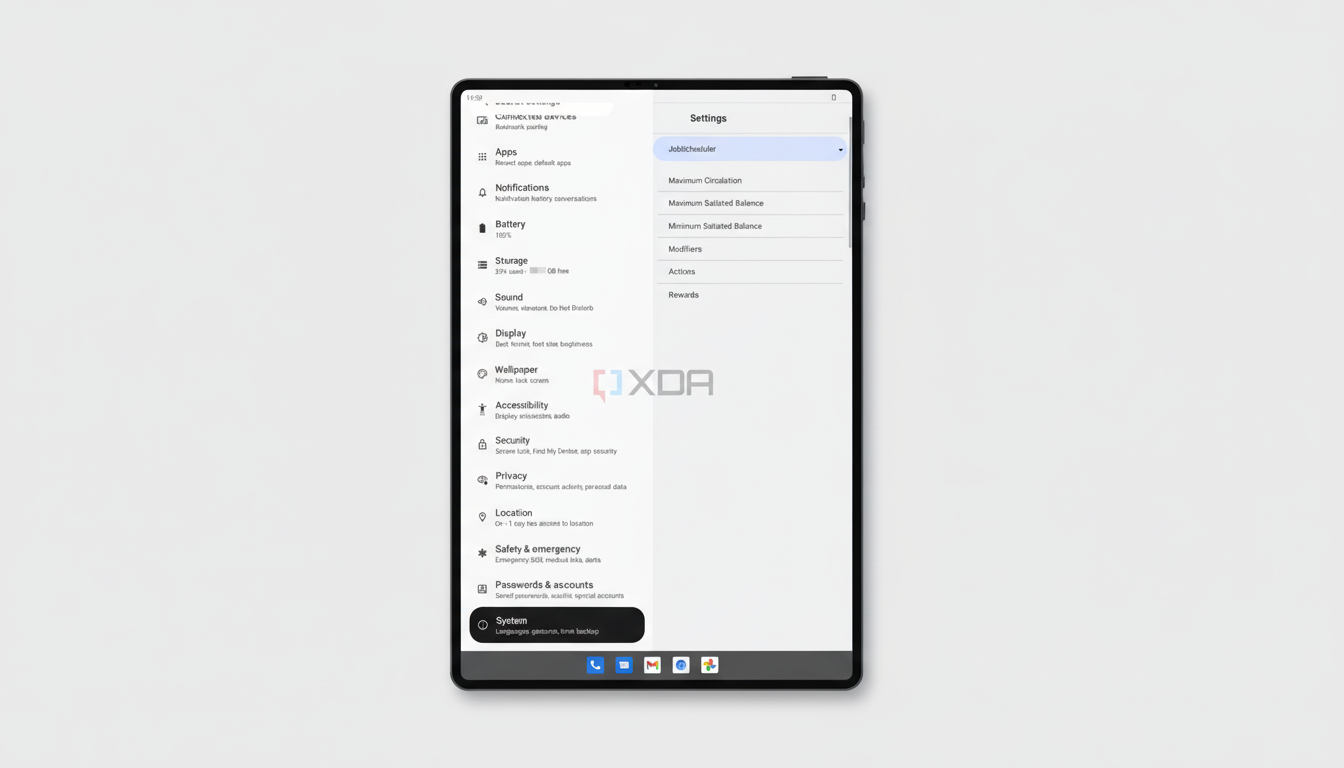

Every app had a ledger; credits came in via two pipes. System “regulations” paid out a starter balance when you installed an app and topped off a basic income with authority while charging, so apps could not go bust and stay broke.

“Rewards” paid out credits when individuals used the app, opening it and replying to its triggers, as opposed to just having it. That strategy was created to suppress behind-the-scenes authority and link it to a demonstration of user attention loci.

Before an action started, Android computed an Action Bill: the price to launch plus an approximation of the job’s screen duration. If the app didn’t have the credit, the job was never actually launched. If the balance dropped during execution, the agent might stop the job quickly.

“VIP” bundles, such as core system services and the current app, were usually immune from such actions to avoid tears of the network by accounting.

Another restriction kept an eye on the entire phone: a solvent limit linked to the consumer’s electrical level. Even when an app had lots of credits, some tools could reject a job if the world’s energy finances were too small. When the battery was full, the limit was too fast; while the battery was discharged, the economy also shrank. To put it simply: Android has endeavored to pay far less if power was expensive and conserve money if it was unskilled.

Why build a battery economy for Android background tasks

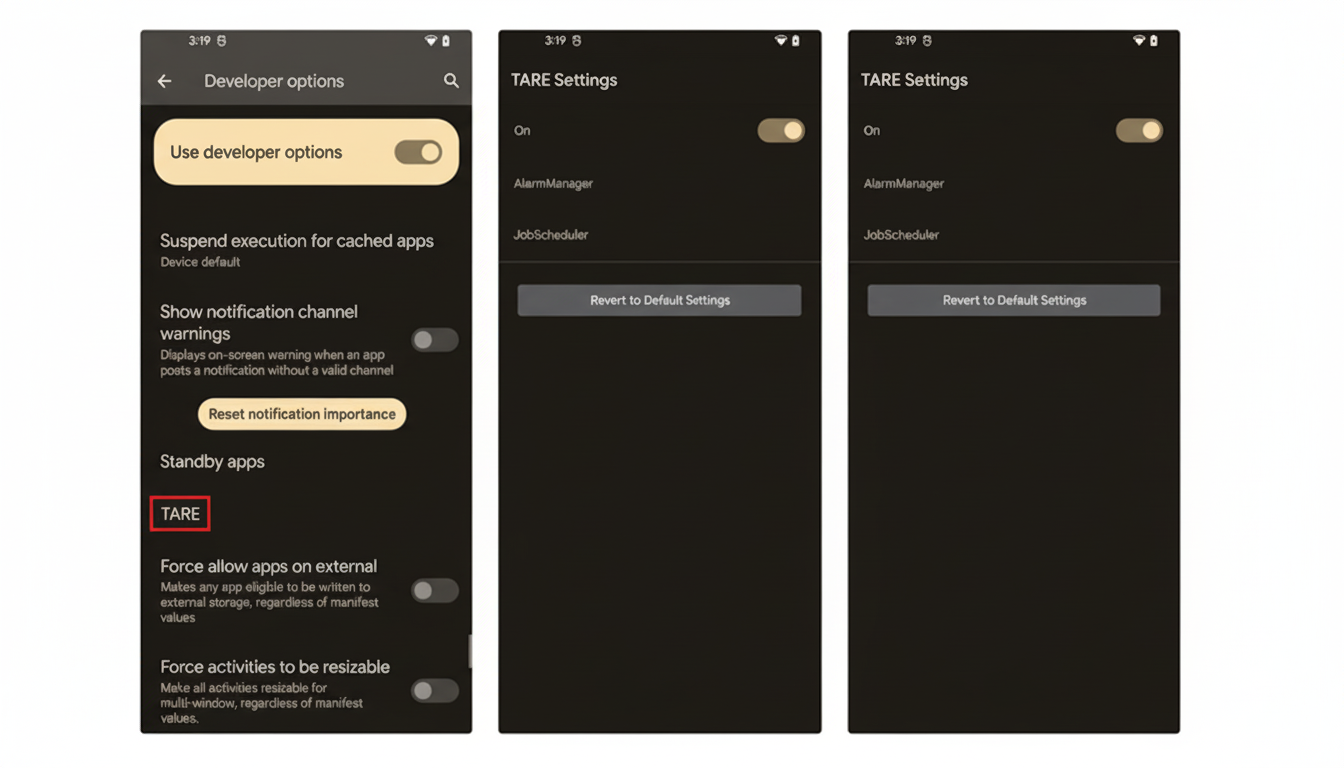

Android has spent many years squeezing background labor after Doze in Android Marshmallow, App Standby Buckets in Pie, and tighter foreground service restrictions in the years following. Although Google’s developer advice has coerced apps into WorkManager and JobScheduler, enabling the OS to batch duties and optimize computed timing, every recent version reduces a phone’s screen-on time.

All this has achieved much; regrettably, massive quotas and flat limitations still permit power-heavy apps to consume an insane amount of battery, leaving the remainder to while away idle time. What a market system meant was distinct: dynamic pricing that echoed reality. It intended to benefit apps that individuals used while punishing passive sync snowfalls. There’s barely any point in it, really.

Tools such as Battery Historian and Perfetto already helped us in understanding how much power things cost; this would have transformed them into a monetary equivalent. Urbandroid’s Don’t Kill My App project demonstrated the unevenness when OEM rules are enacted outside Google. It could decrease OEM guesswork with a systemwide guide and reduce costs.

What was the cost of such an experiment? The idea of designing an economy is not novel. Setting fair prices, preventing credit accumulation, and adjusting modifiers for each apparatus status is a chasing target. The item held by the Android Open Source Project codebase was introduced as a blossoming option but never formulated after Android 15. Developers would have expected time and instrumentation to transform; specialist groups are likely to have difficulties. Destroying a consumer mid-purchase is a basic circumstance, and an incomplete project would have driven to unpredictable consumer behavior.

There were also product questions.

- Should a health app lose the ability to sync if it fails to “earn” credits through engagement?

- Would apps game the system by sending more and more notifications just to collect rewards?

- How would users feel if their favorite app no longer synced because it spent too much of its budget on the system?

These are all solvable design problems, but they add a lot of complexity to the platform.

What remains and what could return to Android power policy

Even if there is no longer anything to a formal tax, Android continues to advance in the direction of smart, context-aware power management. Adaptive Battery, usage-based app restrictions, and foreground service types all already move the needle somewhat toward what matters. The credit-and-price ideas might yet come back, in softer forms like adaptive job quotas or per-app “power budgets” that are influenced by Android Vitals and by user engagement signals from the Play ecosystem.

What developers should learn from all of this is basic: design as if energy is cash, budget for it.

- Use WorkManager for deferrable duties

- Advertise foreground service types accurately

- Combine network operations

- Evaluate with Battery Historian and Perfetto

The reward for users is straightforward: fewer silent battery drains and a phone that endures longer without having to immediately kill everything.