And my father did what millions of Android owners have done when that situation happens — he found the most official-looking button on the screen and pressed it. His phone was flung with assorted PDF readers moments later, none of which solved the problem. It wasn’t just user error to blame. It was a brew of misleading in-app ads, confusing Play Store design and weak guardrails — all happening on Google’s watch.

This isn’t an isolated mishap. It’s a case study in how Android’s ad and app ecosystem pushes nontechnical people into making bad decisions even when they’re trying to do the right thing.

A Fake Update Prompt Spurs a Download Frenzy

It all started with an office suite that he had previously installed. When my dad tried to open a PDF, he’d get exactly one splashy screen telling him that “Unable to read file. Try updating your PDF application,” with an “Update now” button. It appeared as a dialog from the system. It wasn’t. It was an advertisement.

Tap the button, load a shiny new PDF app from the Play Store, install, rinse and repeat. He wasn’t actively looking for an alternative; the ad presented itself as a fix. Only after uninstalling the preloaded office app — and with it, the deceptive ad surface — did PDFs open normally.

Google’s own ad policies, for example, say in-app ads should not falsify system notifications or mislead users about what happens when they tap on one. And yet it continues because enforcement is spotty and punishment is rare.

The Play Store UI Prepares Casual Users for Errors

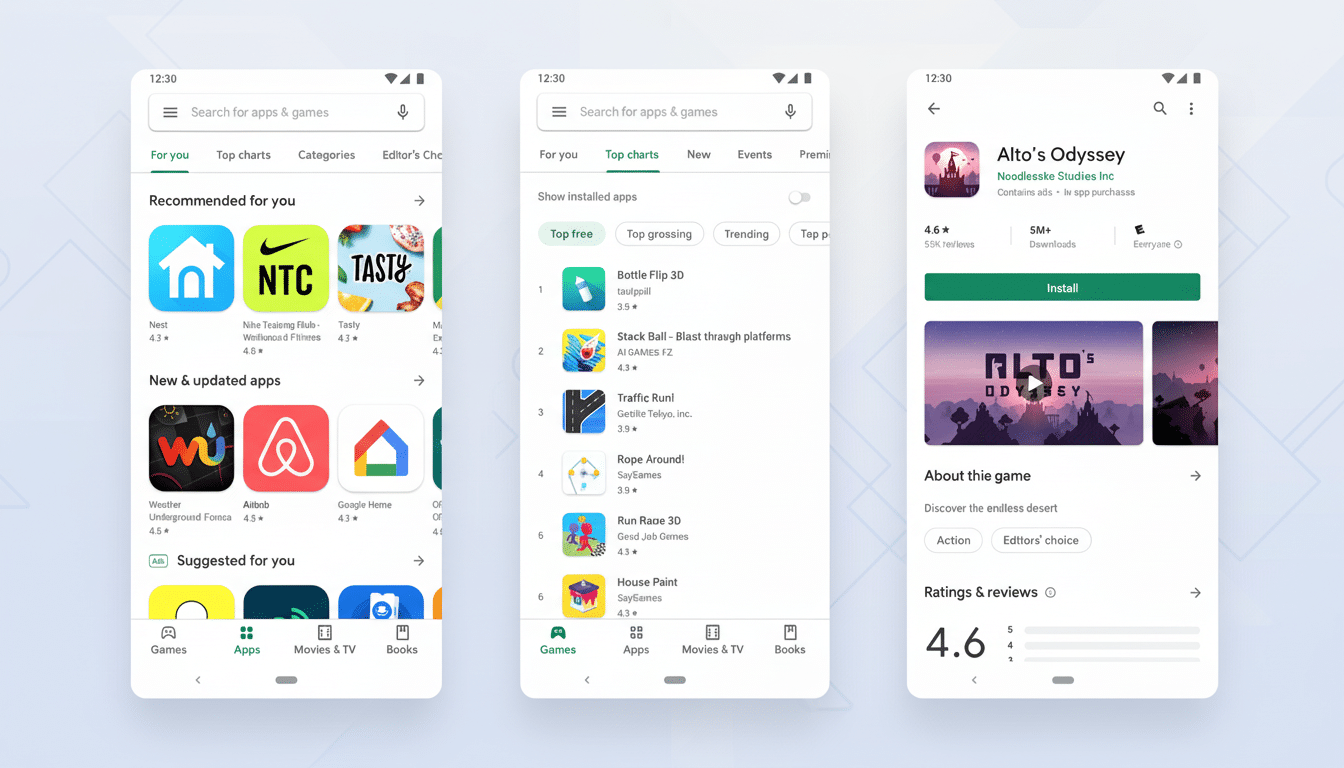

Even if users get to the Play Store, many of them are greeted with an opening screen filled with ads that look like organic results. The “Ad” tag is tiny; the design matches other listings; ratings and installs seem just as big. It’s easy to think the most popular result is the correct one, especially for someone who has been thrown off by an “update” prompt.

Search quirks worsen the problem. Generic search queries such as “PDF opener” can result in nearly identical apps with similar names, icons and boilerplate descriptions — a usability nightmare that only exacerbates poor decisions rather than addressing them.

Shovelware Perseveres Despite Takedown Efforts

The Play Store’s old shovelware issue has never really gone away. The security firm Zscaler has identified hundreds of malicious apps that have sprung up in the store each year, from ad-fraud kits to information stealers, according to findings shared with independent researchers and trade outlets. Google does move — it knocked out more than 180 applications linked to ad fraud with a total of 56 million downloads in one recent sweep — but the pipeline continually fills.

Confidence among users is low. Only 15 percent of people said in a recent Malwarebytes survey that they were confident about being able to identify scams. It’s a poor baseline in an ecosystem where we are fed ads pretending to be system advice, and near-duplicate apps obfuscate the boundary of legitimacy vs. opportunism.

OEM Bloatware and Ad Networks Are Guilty Too

There’s more at stake here than just Google. Phone makers pre-install “productivity” suites that monetize attention with aggressive interstitials, giving rise to more surfaces for deceptive prompts. When those prompts are routed to lightly vetted apps, the user pays a price in confusion, wasted storage and risk.

If Google can certify Android builds and demand minimum security features, it can also demand a less hostile code of conduct around ads for preinstalled apps and more upfront disclosure at the system level for anything pretending to be an update or security alert. Right now, too much of that burden falls on the people who are least able to parse it.

What Needs to Change, and How Users Can Cope

Practical fixes are obvious: Enlarge ad labels, make them persistent across all listing formats; ban any ad creative that copies system UI; demote near-duplicate utilities that lack meaningful features and create a “trusted default” badge for core tasks like PDFs, where human review oversees ongoing audits.

Google has become more rigorous about verifying developers and periodically weeds out bad actors, but the incentive structure continues to favor lazy clones and dark patterns. We could make the math different by making abuse more expensive — through higher scrutiny (e.g. for prepublication), faster ad network bans, or penalties on OEMs that ship adware systems by default.

For families and less savvy users, a short setup checklist is most of the win:

- Uninstall bloatware.

- Set a reliable PDF app as the default.

- Enable Private DNS with a known provider to block most ad and tracking domains.

- Review app permissions monthly.

- Report any ad that looks like a system message.

None of these are silver bullets, but they shrink the surface area for error.

My dad’s phone is OK now. The lesson here isn’t that people should be perfect, it’s that platforms need to stop making the wrong tap feel like the right one. Until that changes, phones like his will continue to be overrun with random PDF apps, and users will keep paying for design decisions in which they had no say.