General Fusion, a long-running contender in the race to commercialize fusion energy, plans to go public through a reverse merger that values the company at about $1 billion. The deal with special purpose acquisition company Spring Valley III could deliver up to $335 million in gross proceeds, a lifeline for a firm that recently cut roughly 25% of its workforce and relied on a $22 million bridge round to stay afloat.

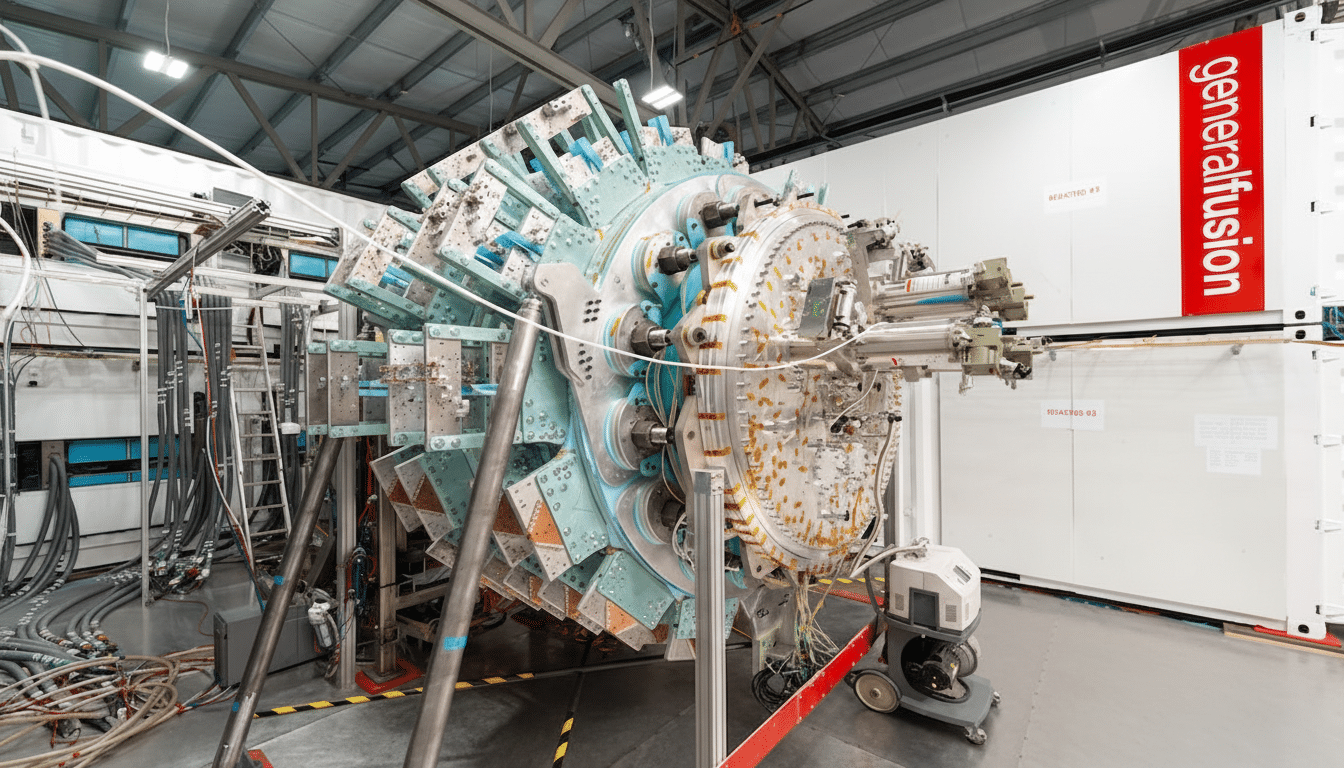

The Vancouver-area startup says fresh capital will accelerate its Lawson Machine 26 demonstration program. Founded in 2002 and backed by more than $440 million in prior funding, according to PitchBook, General Fusion has pitched a cheaper, more compact path to fusion by avoiding the expensive lasers and superconducting magnets used by rival approaches.

A High-Stakes SPAC Bet on Fusion and Public Markets

Spring Valley III is no stranger to energy technology listings. An earlier Spring Valley vehicle took NuScale Power public, introducing investors to small modular nuclear reactors; that stock later slid more than 50% from its peak, underscoring the volatility around pre-revenue energy hardware. Spring Valley affiliates are also working on a merger with Eagle Energy Metals, a uranium play. The track record is a reminder that SPAC proceeds can be whittled down by redemptions and market chop, even when PIPE investors participate.

Against that backdrop, General Fusion’s $1 billion enterprise value reflects both scarcity and skepticism: scarcity because private fusion capital is consolidating around a handful of credible teams, skepticism because repeatable net-energy gain, regulatory clarity, and bankable plant costs all remain unproven. Management says the money will be directed primarily to engineering, supplier partnerships, and the LM26 program rather than long-lead commercial construction.

Inside General Fusion’s LM26 Approach and Design Details

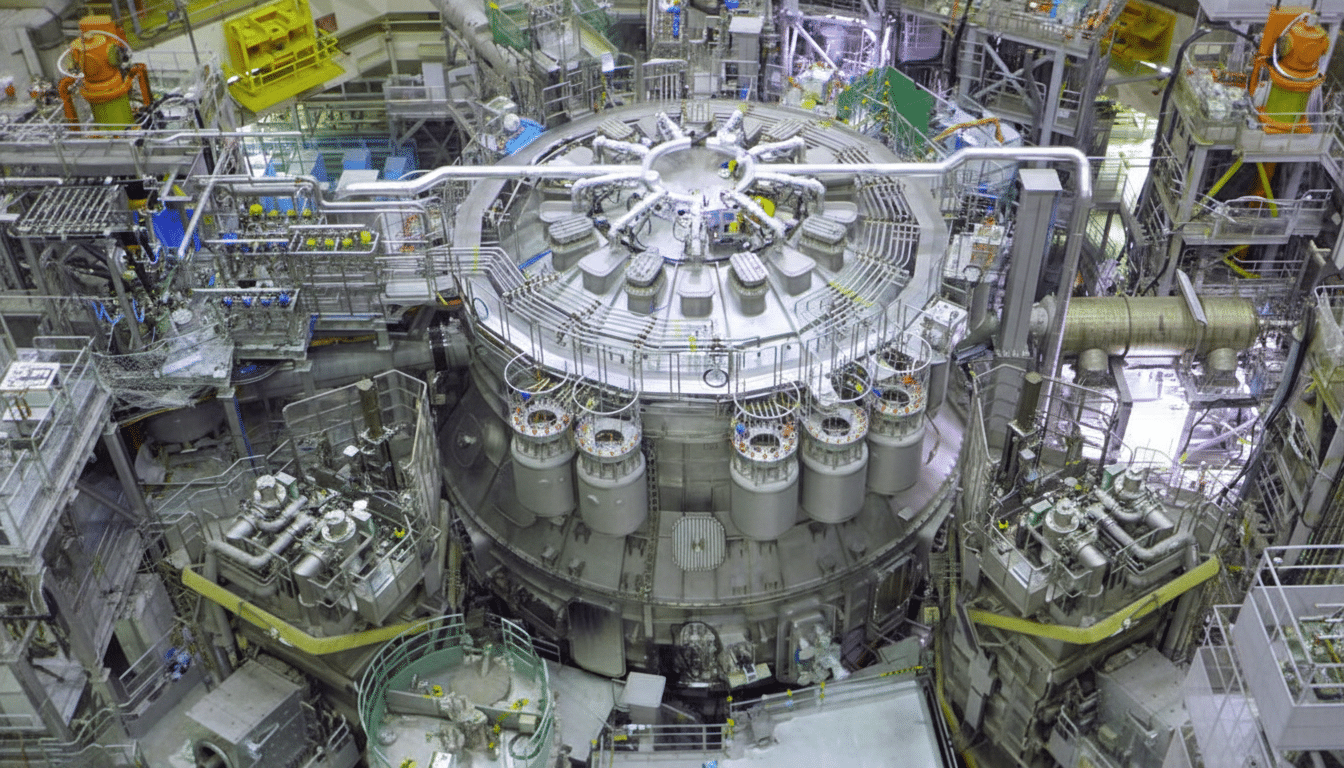

General Fusion aims to achieve fusion using a variant of inertial confinement. The company’s design compresses a fuel target inside a liquid metal cavity, driving pressure waves with synchronized, steam-powered pistons. The liquid lithium liner both confines the plasma and serves as a heat-transfer medium for a conventional steam cycle. It’s an elegant idea: use relatively inexpensive mechanical systems and commodity heat engines, rather than banks of lasers or complex superconducting magnets.

The concept draws inspiration from the U.S. National Ignition Facility, which has demonstrated fusion burn using lasers to implode fuel pellets. General Fusion’s bet is that pistons and a rotating, liquid-metal cavity can deliver sufficient compression at a fraction of the cost and complexity. The company has previously targeted scientific breakeven—producing more fusion energy than the energy used to trigger the reaction—on LM26. That milestone, while meaningful, is distinct from commercial breakeven, which requires net electricity to the grid after conversion and plant overheads. The firm has not recently reiterated the exact timing for those goals.

Why Investors Care About Fusion Now and Future Demand

Two tailwinds are hard to ignore. First, power demand from generative AI and cloud computing is surging; BloombergNEF projects data center consumption could nearly quadruple from today’s level over the coming decade. Second, electrification of transport and heating is poised to lift total electricity demand by up to 50% as EVs, heat pumps, and industrial electrification scale. General Fusion’s merger pitch explicitly cites these shifts, positioning fusion as firm, zero-carbon capacity that can complement variable wind and solar.

Market signals are starting to align. Helion Energy, another fusion startup, signed a conditional power purchase agreement with Microsoft, suggesting that large corporate buyers are willing to underwrite early volumes if timelines and costs pencil out. Traditional nuclear is seeing renewed interest, too, as utilities and hyperscalers search for dependable clean power. For investors, the question is whether fusion can deliver similar reliability without the cost and siting challenges that have dogged fission.

Key Risks and Milestones to Watch on the Path to Fusion

Technology risk is paramount. General Fusion must demonstrate repeatable compression, stable plasma conditions, and credible energy gain, followed by integrated thermal conversion that proves the lithium liner concept works end-to-end. Independent validation will be critical. On the finance side, SPAC redemptions could shrink proceeds, forcing the company back to market sooner than planned. Execution risk—supplier readiness, system synchronization, materials durability—looms large for a design that relies on tightly timed mechanical impacts.

Commercialization will also hinge on regulatory pathways, cost-out roadmaps, and early offtake agreements with utilities or data center operators. If LM26 hits its targets and the company can chart a line of sight to competitive levelized costs, fusion’s promise of abundant, carbon-free, around-the-clock power would move from aspiration to realistic option. If not, the public markets are likely to be unforgiving.

For now, the reverse merger gives General Fusion a second wind and a public currency. In a sector where timelines stretch and capital demands rise, that might be the most valuable energy source of all: time.