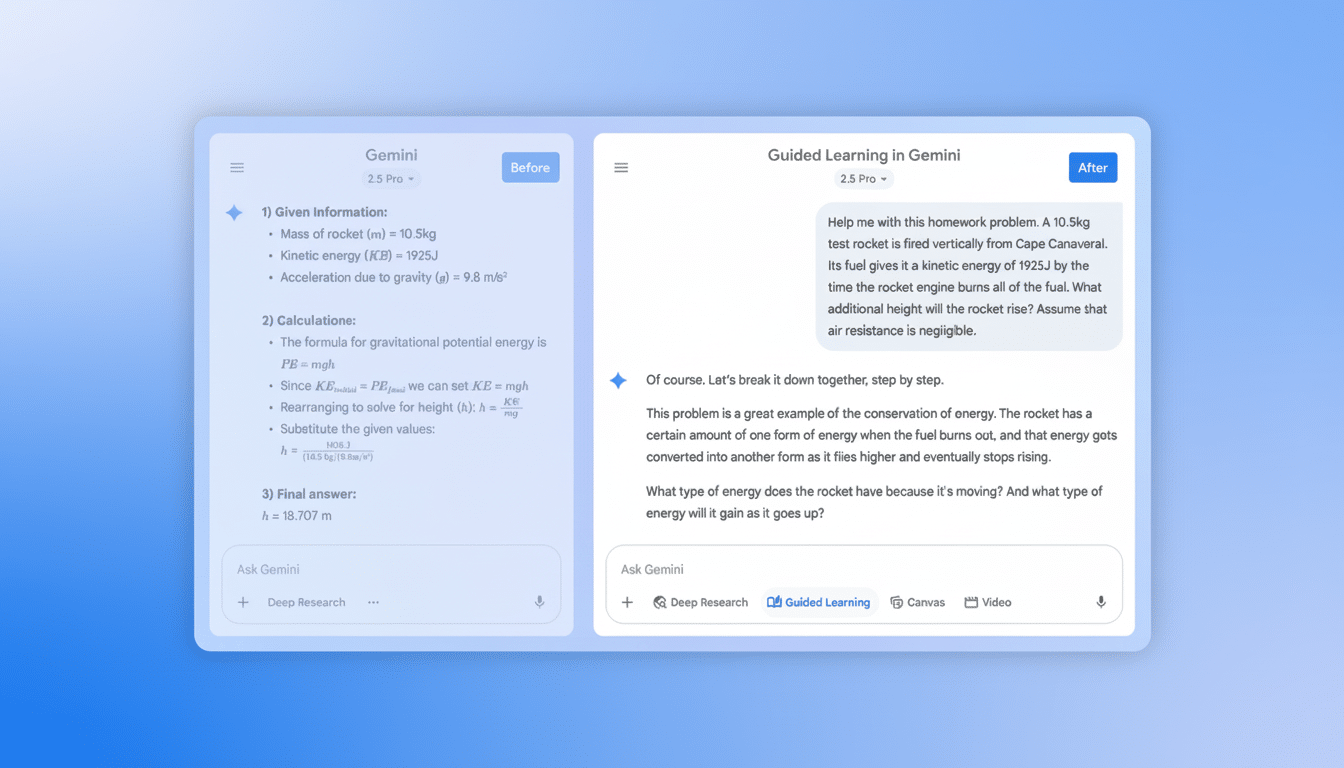

I went into Gemini’s new Guided Learning mode as someone who is skeptical of explanations that unfold one step at a time, and I came out feeling both invigorated and annoyingly obtuse. On its best days, the feature is like a patient tutor who can quiz, diagram, and simplify just about anything. At its worst, it’s a stiff interlocutor that over-questions you, over-metaphors you, and under-explains you when what you really want is depth.

What the feature gets surprisingly right

Guided Learning is a dynamic study partner, gap-filling methodologically very well. Given a large starting prompt, the system suggests a reasonable learning path, tests you with tiny questions, and will even spin up flashcards or short quizzes on demand. That mix reflects research on retrieval practice — studies from cognitive scientists like Henry Roediger and Jeffrey Karpicke have found that engaging in low-stakes testing often, over time, helps improve long-term memory more than simply re-reviewing or rereading material does.

It cleared up some of the self-hosting basics, anyway.

I could inquire about the practical differences between setting up a reverse proxy and going with a tunneling service, what trade-offs would be important for someone who’s just starting out, and where security pitfalls tend to lie. The model constrained its explanations in bite-size chunks and adapted when I asked for plainer or more technical language. It even drew quick diagrams to help you see the flow of traffic — cruddy, but they provided relief while thinking about networking paths.

The ability to change direction on a dime is another strength. I went from homelab networking to central sensitization — relevant for conditions like fibromyalgia and chronic migraine — and it turned the corner without losing coherence. It pried apart concepts, described Substance P’s role in the pain signaling structure, and didn’t leave me buried in jargon. A tutor with immediate breadth between computing and neurology can be seen only in the human case; that its existence appears to be copyable is one of the model’s biggest assets.

Where it fails: A script written in stone a mile high

The friction begins when the system finds a way to ask a question in practically every exchange — even if you asked your own, direct question or made clear that you were starting from zero. Sometimes Socratic prompts can be invigorating, but here they are a default tic. I’d say, “What is Substance P’s role in fibromyalgia?” and instead of responding to my question, I’d be asked what I already knew about the peptide. Repeatedly. Even after pleading for “fewer questions,” the next round saw… another question.

Worse still, more often than not, the balance of any given response tilts away from substance. About a third of the response has sounds of encouragement, another third is a question, and the rest conveys new information. That’s fine for warm-up or review; it is counterproductive when you require a clean, uninterrupted explanation or a deep technical dive.

The other misfire is with metaphor overuse. Atmosphere is good to have — until the analogies begin to contradict one another across turns, or supplant genuine mechanics with feel-good imagery. Some nimble analogies clarify; a cascade of mixed metaphors confounds.

What learning science suggests for guided learning design

The tension here corresponds pretty well to the existing research. The Socratic approach generally works best when learners have some foundations from which they can reason. For beginners, the “worked-example effect” identified by John Sweller and others holds that clear, step-by-step demonstrations lessen cognitive load and speed early mastery. Or, in other words, teach before you quiz.

So too is retrieval practice powerful, if it is aimed at material that has been meaningfully encoded. When the system’s quizzing cadence is too far ahead of comprehension, it can lead to superficial processing and possibly user frustration. Education researchers and organizations such as the Education Endowment Foundation repeatedly promote explicit instruction paired with checks for understanding, not a single question script that works for all.

There’s also a usability angle. Studies in human-computer interaction highlight repeated requests and conversation loops as likely causes of abandonment. When you’re learning, that loop can be more than annoying — it disrupts flow, the state of mind most strongly associated with persistence and deeper engagement.

How Gemini might become a star tutor with better controls

Both of these are fixable things with settings and smarter heuristics. A bare-bones “instruction mode” switch — Explain First, Balanced, or Socratic — would also tailor the tool to where a learner’s at. A control for question frequency and the ability to pin a preference: “No questions for next three turns.”

When the user queries directly, the model ought to respond directly first and then provide food for thought. Metaphors should be optional and coherent; a “literal mode” would aid in technical areas. And when a loop is identified, the system should auto-summarize the recent transaction, then propose two specific next steps: go deeper or switch to practice problems.

Lastly, lean more into things that are working: better diagrams with labeled steps, spaced review schedules for the flashcards, and quiz items that increasingly build to transfer tasks. Those are aligned with evidence-based principles from cognitive psychology and would amplify the feature’s best attributes.

Bottom line: a promising tool that needs better pacing

Guided Learning can light a fire under curiosity, unpack difficult concepts, and bundle practice in a way that makes it feel rewarding.

But its demand for relentless questioning and analogy-laden answers can sometimes get in the way of what learners really ask for: a clean, crisp explanation. Take control of pedagogy and pacing away from users, and this could grow from interesting to essential.