Florida is constructing a new toll highway near Orlando that will do something no roadway in the United States has ever done: charge drivers for using electricity. A small section of the Lake/Orange Expressway (State Road 516) is set to link U.S. 27 with State Road 429, and it will have wireless charging beneath its surface that enables EVs to be charged when on the go.

How the Wireless Charging Lane Works in Florida

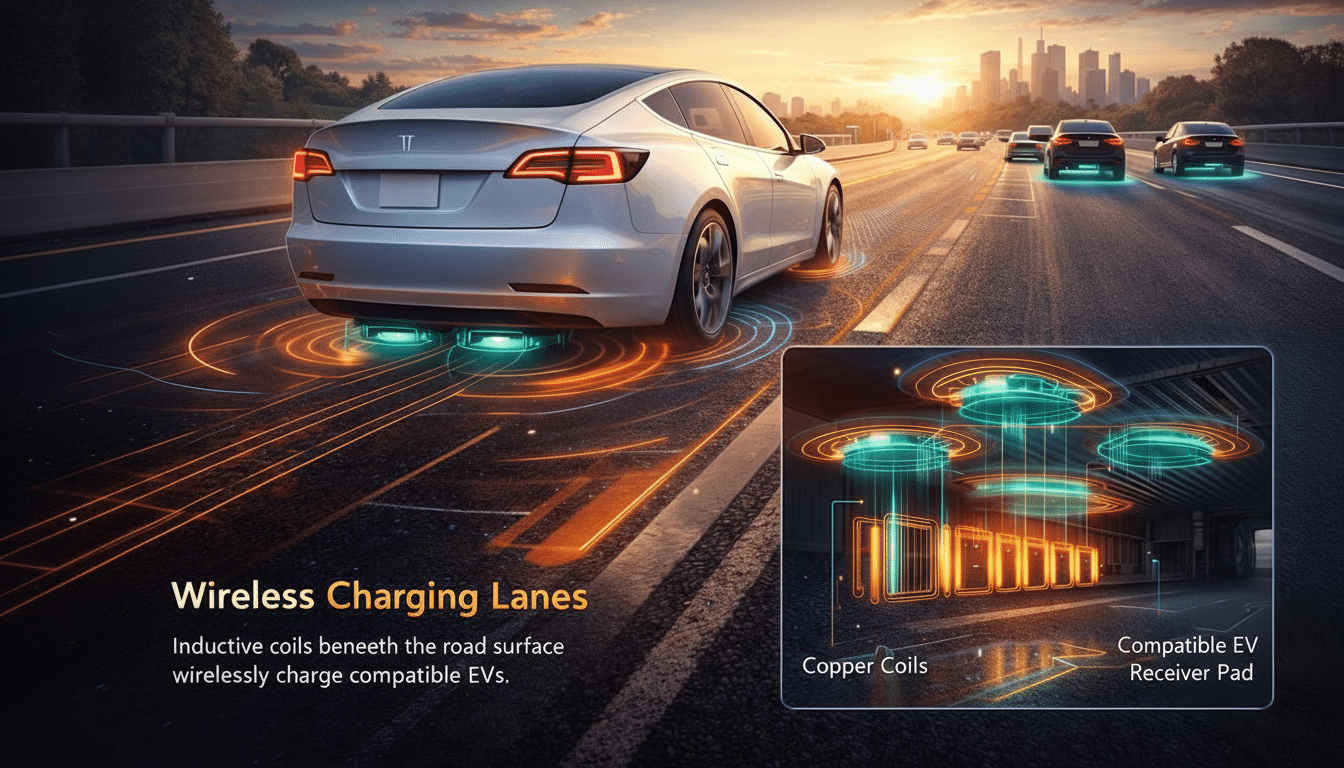

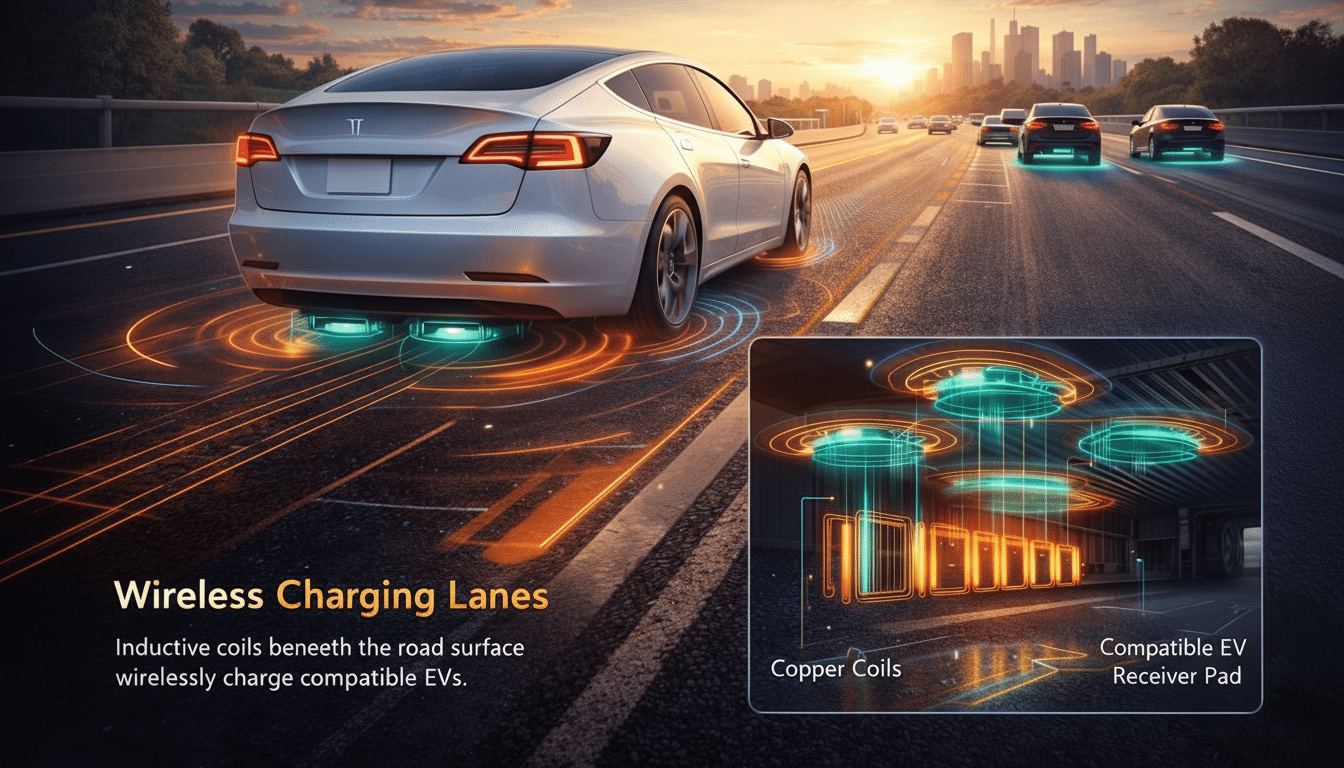

Under the pilot, they’ll generate a magnetic field by using inductive coils embedded in the roadway to transfer energy to a receiver mounted on the underside of a vehicle. As the car, bus, or truck drives over powered sections, juice flows into the battery without your needing to plug in — ever. Details of the project plans as described by regional officials and reported by TechSpot indicate the energized stretch will measure about three-quarters of a mile, with receivers able to accommodate up to 200 kilowatts — enough to help extend an EV’s range in ways that are more meaningful than wireless smartphone charging but far below what a full charge would take.

Dynamic wireless charging relies on the same concepts as static systems, but has to keep an energy connection in place while traveling at highway speeds and through inches of asphalt. Engineers usually adjust the system to work at specific frequencies and divide coils so that only a portion under a vehicle is charged, improving efficiency and safety. The industry is converging on interoperability through standardization efforts like SAE’s J2954 family of documents, which seeks to establish a common language between vehicles and road hardware.

A Living Testbed on Florida’s New SR 516 Corridor

The CFX is developing SR 516 as a smart corridor that integrates transportation with technology and environmental design. Alongside the wireless charging pilot, there are plans for solar installations that will power roadside systems, wildlife crossings that protect habitat, and a shared-use path for cyclists and pedestrians. The expressway will open in phases later this decade, and engineers will have a chance to collect data on methods of construction, power delivery, and pavement life.

The perfect proving ground is the state of Florida. Now the second-largest state in terms of EV registrations, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, Florida gets that mix with its blend of commuter traffic and freight movement that make up real-world duty cycles for testing heavy vehicles. If the pilot proves it performs well in heat, humidity, and seasonal storms, it may bolster the case for scaling the technology elsewhere.

Why This Might Change EV Economics for Fleets

Ultimately, continuous top-ups along key corridors might allow vehicles to carry smaller batteries without sacrificing range — a huge thing for trucks and buses, in which the mass of the battery and its associated cost weigh heavily on total ownership costs. Modeling from national labs and industry pilots suggests that dynamic charging lanes can lead to double-digit reductions in battery capacity (on the order of 20–40 percent in some freight scenarios) while still staying on schedule.

Vallee believes more widespread adoption could also relieve some of the burden on stationary fast-charging hubs, which often need grid upgrades and big pieces of real estate. Rather than supplanting plug-in charging, dynamic lanes would complement it, adding energy during the most predictable times and locations: on busy commuter and freight corridors. That dovetails with the buildout of public charging paid for by federal and state programs and by private networks, especially as utilities prepare for heavier loads on highways.

Lessons From Other Pilots in the U.S. and Abroad

The Florida approach is part of a wave of real-world tests. In Michigan, the state worked with Electreon to create a short inductive roadway in Detroit within a broader mobility district. The state transportation department and Purdue University are looking into conductive concrete ideas for truck corridors in Indiana. Overseas, the Gotland project in Sweden showed dynamic charging for buses and trucks on public roads, and Germany tested overhead “eHighway” catenary systems for freight. Each model trades off hardware complexity, vehicle modifications, and cost in different ways; Florida’s in-road induction dispenses with pantographs or overhead wires, seeking a more unobtrusive fit into existing road profiles.

Hurdles Still to Clear Before Wider Deployment

Cost and coordination are still the largest concerns. Mounting coils, power electronics, and utility connections inflate construction and maintenance budgets, and early pilots elsewhere have commanded multimillion-dollar price tags even for short stretches. Agencies will also require clear business models to bill, operate, and upgrade the vehicles — as well as a mechanism for correctly metering energy per vehicle.

Vehicle compatibility is another important consideration. Only EVs with the appropriate receiver will be able to benefit; as a consequence, standards and OEM adoption are vital. On safety, the researchers say systems are engineered to comply with international exposure standards and only power up when a vehicle associated with one is nearby. Agencies will still check for electromagnetic interference and gauge pavement life cycle and performance in standing water before advancing the new technology more broadly.

What to Watch Next as Florida Builds SR 516

Once construction goes forward, see whether the energy-delivered-per-mile data bears out, whether the ramp offers good performance at various speeds, and how Florida’s climate affects aging over time. It is currently unclear if bus fleets and logistics operators will participate, but heavy vehicles should ultimately benefit the most from dynamic charging. If the pilot on SR 516 is dependable and cost effective, Florida can assist in moving wireless road charging from novelty to infrastructure, making a sometimes invisible technology an everyday range extender for EVs.