F-Droid, the venerable repository of free and open-source Android software, says that Google’s upcoming developer identity rules could eviscerate third-party Android app powerhouses like itself. The group contends that the plan would hand Google veto authority over which developers can deliver apps on certified Android devices, even if those apps are obtained outside of Google Play.

The matter at hand is a new rule that would permit installs only if the app developer’s identity has been verified by Google. The supporters cast the action as a security upgrade. F-Droid describes it as a structural change which saps user choice, the open-source model, and the possibility for independent marketplaces to compete on equal terms.

How Google’s Verification Strategy Works on Android

Google already requires developers who publish on Google Play to undergo identity checks. The firm is now going to expand that verification for every path the app takes to be installed onto these certified devices, such as from installations prompted by alternative stores and direct downloads. In practice, that would make Google the gatekeeper of identity for Android’s entire software supply chain.

Google says the rollout will start in a small number of markets such as Brazil, Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand before expanding globally. That phased approach also implies that Google will be testing the technical enforcement of this on the whole-ecosystem impact before scaling.

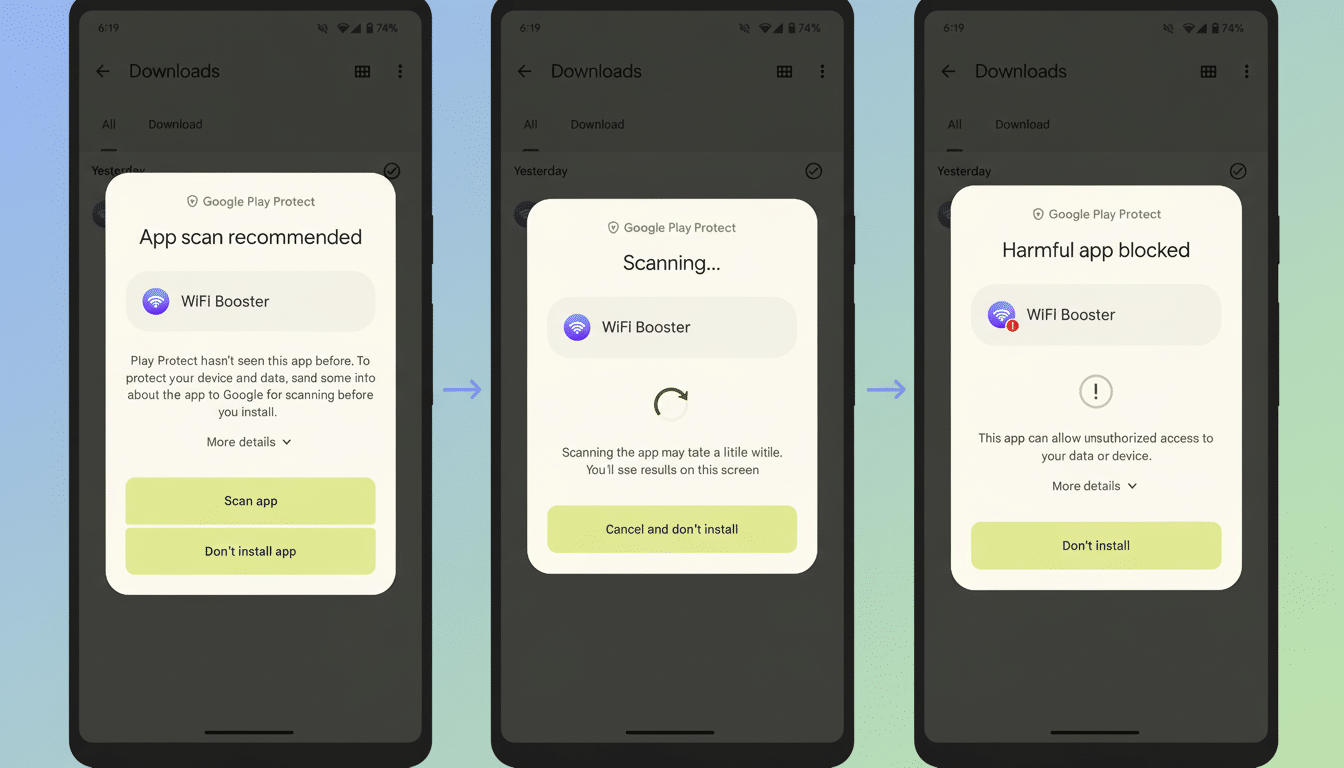

The company links the change to its larger anti-malware stance, including Play Protect scanning, the App Defense Alliance, and integrity attestation tools. In the past, Google has said that devices that are based exclusively on Play see significantly lower rates of harmful app installs than those that sideload apps — a data point Google uses to promote tighter restrictions across its distribution network.

Why F-Droid Says It Cannot Comply With Google’s Plan

F-Droid definitely does things differently from a commercial storefront. Its repository includes thousands of free and open-source apps which are compiled from their publicly auditable source code. F-Droid keeps metadata and builds the apps itself, often also re-signing packages so that users can have a consistent cryptographic signature provided by the store. Reproducible builds allow developers and users to verify that the published code actually matches the source.

Google’s approach, as described, would tie the right to install to a developer identity verified with Google. F-Droid argues that it cannot force upstream developers to create a Google account (for the purpose of granting them access to the issue tracker). F-Droid also cannot freely hijack package identifiers and signatures for projects it doesn’t own, as that spells entering exclusive distribution pairings and preventing compatibility with users who want to mix sources.

In other words, the new requirement undermines store-level trust in exchange for a Google-run developer registry. F-Droid says this flips Android’s openness on its head, by letting one company be the arbiter of who gets to publish software at all.

Claims of Security, and the Evidence Google Cites

Google’s reasoning for the move is simple enough: Verified identities make life tougher for scammers who jump from throwaway account to throwaway account. The company cites years of investment in Play Protect, machine learning detection, and coordinated takedowns through the App Defense Alliance as evidence that centralized defenses work at scale.

F-Droid, by the way, argues that identity checks would not be a panacea. Deep-pocketed fraudsters can still slip through basic verification; true-blue developers (especially volunteers and little open-source crews) might be dissuaded by new walls. The coalition also points out that adware and fleeceware have “wreaked havoc” over and over in major stores, despite known remedies, emphasizing once again that curation and transparency count as much as identity vetting.

On F-Droid, the code for all apps you see is viewable to anyone and auditable by everyone: builds are reproducible (what you compile in F-Droid is byte-for-byte identical to what is released as an APK from upstream) and trackers are either listed or removed when possible. That’s a complementary security model, the project argues: users and maintainers can verify what the software does, not just who uploaded it.

The Competitive Stakes for Android’s App Ecosystem

It’s a requirement that Amazon Appstore and Samsung Galaxy Store would likely be able to handle, since they already have compliance teams and direct contact with Google. The greater burden would fall on small marketplaces, nonprofit catalogs, and niche developer communities that rely on decentralized governance and volunteer labor.

Critics argue the change would further skew Android in favor of a single distribution gate and into vaults already controlled by Google—over which developers get to effectively “count.” That could invite antitrust scrutiny from competition authorities and consumer protection regulators, especially in jurisdictions where the law promotes open platforms and alternative app distribution.

For users, the concern is that they’ll have fewer places to discover privacy-first or experimental apps that big storefronts may not take a chance on. For developers, it’s a matter of control over package names and signing keys, and the right to distribute outside Play without bowing down to Google’s identity regime.

What to Watch For as Google Tests Developer Verification

F-Droid is calling on policymakers to think through the implications before enforcement becomes more entrenched, and it’s urging users to lobby regulators in favor of protecting true sideloading and third-party stores.

Android, the project says, should support multiple trust models and other methods of verification such as store-level validation with flexible paths for developers to opt out (as envisioned by industry-standard code signing without reliance on a Google-controlled ID).

A middle path might be a federated system: have established app stores vouch for developers within their ecosystems, require strong cryptographic signing, and maintain Play Protect’s scanning—but without making Google the sole identity provider. That would set a higher bar on abuse while maintaining the diversity that made Android appealing to tinkerers, nonprofits, and indie developers in the first place.

Testing has started in a few countries as the potential impact on alternative stores becomes clearer.

The question is whether Google’s security aspirations can coexist with an Android ecosystem still conducive to independent distribution—and in which projects like F-Droid can survive.