A new smart home line says goodbye to Wi-Fi and hubs in favor of on-device voice control with the promise of faster response time, an easier setup and a smaller attack surface. Emerson’s SmartVoice appliances perform their voice recognition locally, which means you can talk directly to the appliance rather than sending your words through a cloud service or a companion app.

The idea feels almost retro in a market that is infatuated with cloud ecosystems and automation routines. But it’s timely. With homes now adding dozens of connected devices, the lure of products that don’t burden the network — or expose it to the larger internet — has increased. Offline voice control also avoids the privacy trade-offs that accompany third-party assistants.

How offline voice control operates on SmartVoice devices

Instead of sending audio to the cloud, SmartVoice products execute commands on a tiny embedded processor optimized for speech functions. This “edge AI” system works via a wake word and a small speech model trained on a small vocabulary — i.e., with words like power, timers, speeds, temperatures and cooking presets.

It’s a trend across the industry, with vendors delivering low-power neural accelerators along with fuel-efficient keyword spotting. The advantages are real: near-immediate replies, not depending on home internet and reduced data exposures. It also makes sense for simplistic appliances where a full app suite would be excessive.

What Emerson is shipping in its SmartVoice lineup

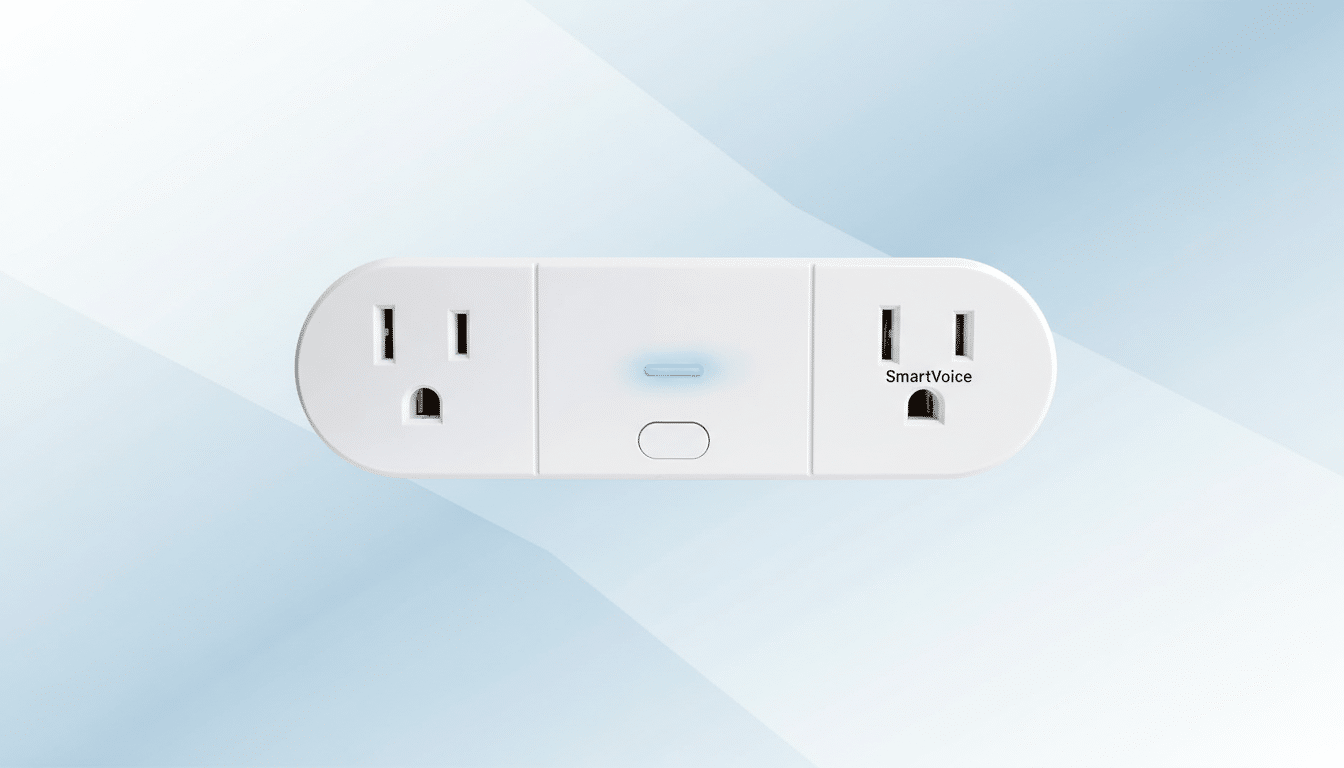

The SmartVoice offerings range from everyday stuff: tower fans in various heights, fan-heaters, smart plugs and power strips (all on their own schedules but scheduled en masse with other compatible Cync devices), air fryers in mid and large sizes. The air fryers will respond to an extensive list of commands — over a thousand phrases with around 100 of them being cooking presets — while the other products recognize a fewer, but still useful, set of controls.

Each piece of hardware answers to a basic wake word related to its purpose. A heater could listen for commands such as “turn on,” “change temperature” or “timer 30 minutes.” The air fryers come with preprogrammed recipes, so a spoken dish name can automatically adjust the time and temperature. Physical buttons still offer manual control and there’s no account to sign up for or router to reconfigure.

Why this offline approach is important for device security

Privatizing those appliances removes a hulking source of risk: exposure to the public internet. Events such as the Mirai botnet proliferated by exploiting vulnerable connected devices at scale. Consumer IoT has been repeatedly warned about for having weak default credentials, unencrypted traffic and inconsistent patching by both CISA and OWASP. The cyber threat intelligence group of Palo Alto Networks, called Unit 42, said that a large percentage of the traffic from IoT devices still flows unencrypted, and thus eavesdropping or hijacking is easier when your device is connected (online).

By design, you can’t get to any of those offline voice appliances from the outside, or enlist them into botnets. They are not sending voice clips to a server, either, which lowers the possibility of data collection or accidental cloud storage of sensitive audio. For a lot of families, that will be the thing.

The new security trade-offs and practical limitations

Removing Wi-Fi from the loop doesn’t make a device invincible. Always-listening microphones draw an entirely new class of attacks, from spoofed voice commands to unintended wakeups. Proofs of concept like DolphinAttack (ultrasonic voice injection) and the Light Commands project (laser microphone manipulation) illustrate how sensors can be manipulated even without a person speaking in the room. Sure, those are lab results that make the point why robust wake word verification and anti-spoofing are so important — even for offline gear.

Safety is another axis. Similarly, heaters and kitchen appliances require conservative defaults, auto shutoff and tip-over/overheat sensors. For voice-only triggers, installing guardrails, such as a short button press for riskier moves or prompting for a confirmation phrase before previously vetted actions are taken, can decrease the likelihood of an inadvertent command resulting in danger.

Updates are a practical challenge. No Wi-Fi? Firmware patches can get there only by USB, a companion app over Bluetooth or at service centers. That can delay response to discovered vulnerabilities. NIST advice (NISTIR 8259A) and the OWASP IoT Top 10 highlight the importance of secure update mechanisms and vulnerability disclosure policies; potential buyers should verify signed firmware, a published support window, and a clear process for applying fixes.

Regulatory signals are mixed. Both the FCC’s Cyber Trust Mark and the UK’s Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure regulations center on connected products, so an offline model may be outside of labeling programs even if it is more private. Everyone is hedging that it will, and while there are things manufacturers can do now in the hopes of that being the case, they should still be doing what’s listed as table stakes here: unique creds whenever possible; secure boot; a software bill of materials.

Who this helps and what to watch for with offline gear

Households struggling with spotty internet, renters who can’t install hubs and privacy-conscious buyers who don’t want to set up cloud accounts may see immediate value. Latency-free voice control is accessible, and not overloading your (most likely) already straining router is always a good thing.

There are trade-offs. When you are offline, you lose remote control and smart home routines; you can’t check its status while away. A local-only Bluetooth option would solve a lot of this for nighttime changes or accessibility without reintroducing cloud risk.

Big picture, the whole Emerson decision highlights a larger reset in smart home design: not every product needs to be connected to the internet in order to feel cutting-edge. If vendors combine offline voice with the kind of safety engineering one already finds in many cars, defendable local security and a clear upgrade path for our appliances, gadgets that listen but don’t phone home might then drive the obvious logic.