Emerald Fennell has surprised Gothic drama devotees by leaving one of Emily Brontë’s most infamous moments off the screen. Despite previously citing Wuthering Heights as inspiration for the graveyard shock in Saltburn, Fennell’s new adaptation pointedly omits Heathcliff’s exhumation of Catherine—because her film ends with Cathy’s death, long before the novel’s macabre late chapters.

Why That Grave Scene Matters in Brontë’s Novel

In the book, Heathcliff compels a sexton to open Catherine’s grave years after her burial, even instructing that both coffins be adjusted so their remains can lie side by side. The episode fuses bereavement with obsession, a hallmark of 19th-century Gothic intensity. Literary critics—from Terry Eagleton to Juliet Barker—have long pointed to this moment as the culmination of Heathcliff’s ruinous fixation, where romantic longing shades into the uncanny.

- Why That Grave Scene Matters in Brontë’s Novel

- Fennell Stops the Story Before the Macabre

- Dodging Self-Repetition After Saltburn’s Release

- Ratings Risk and the Realities of Distribution

- A Longstanding Adaptation Precedent in Cinema

- Thematic Payoff Without the Shovel in the Graveyard

- Adaptation as Interpretation, Not a Literal Inventory

Fennell Stops the Story Before the Macabre

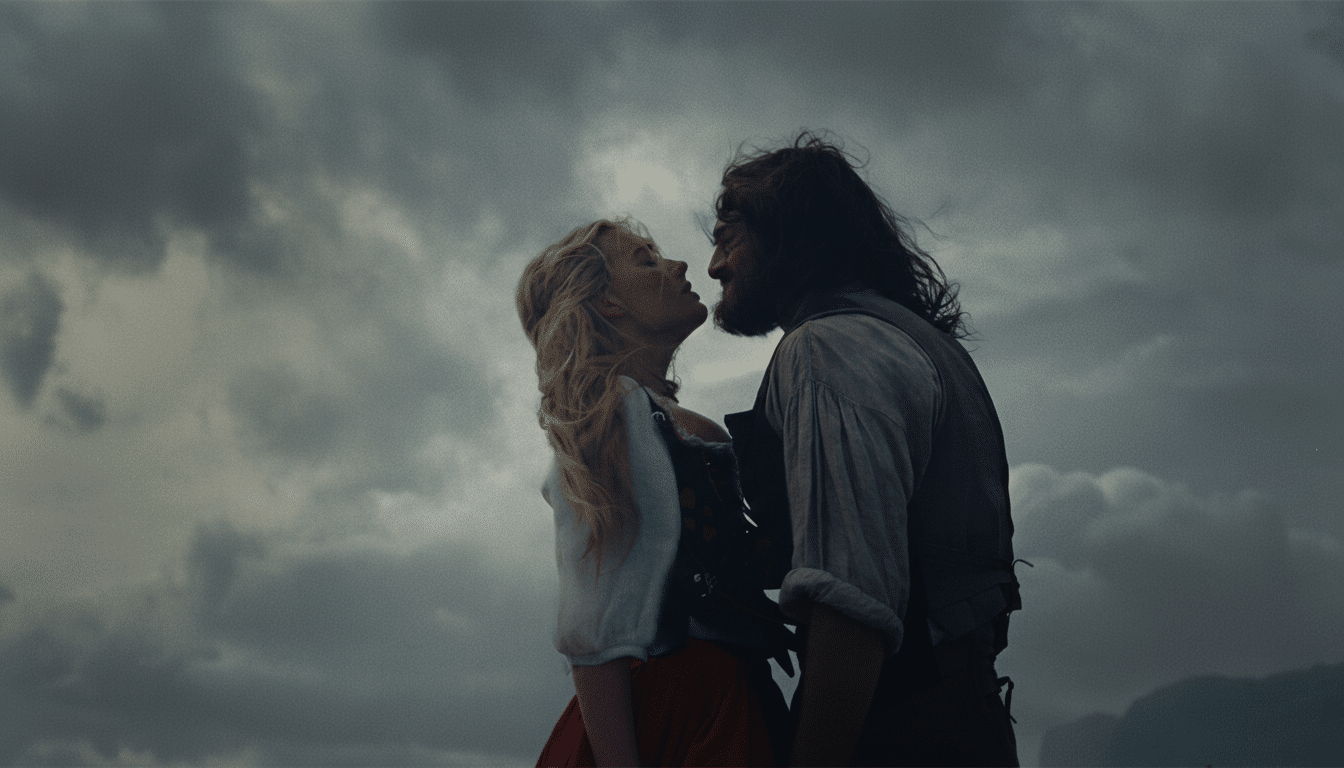

Fennell’s Wuthering Heights adapts only the novel’s first movement, concluding with Catherine’s death. That structure excludes not only the grave sequence but also Heathcliff’s elaborate revenge and the next-generation plot that reshapes the moors’ power dynamics. The choice narrows the lens to youth, desire, and class aspiration—what Fennell has described in press as her “14-year-old self’s” reading of the text. With Margot Robbie as Catherine and Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff, the film concentrates on the formative injuries that make later monstrosities legible, without depicting those extremes directly.

Dodging Self-Repetition After Saltburn’s Release

There is a strategic creative calculus here. Fennell told BuzzFeed that Saltburn’s notorious burial-mound sequence drew from the Gothic, explicitly nodding to Wuthering Heights. Re-staging Brontë’s exhumation now would risk echoing her own viral set piece—and letting the conversation collapse into sensational déjà vu. By refusing the obvious provocation, Fennell sidesteps easy headlines and signals that her adaptation isn’t a greatest-hits reprise of Saltburn’s taboos.

Ratings Risk and the Realities of Distribution

There’s also the pragmatic factor. Necrophilia-adjacent imagery pushes into ratings gray zones that the MPA and BBFC traditionally flag as grounds for the most restrictive classifications. Those labels can shrink a film’s theatrical footprint and complicate platform placement. Filmmakers often calibrate intensity to safeguard reach; here, ending before the grave scene preserves the Gothic mood without flirting with distribution red lines.

A Longstanding Adaptation Precedent in Cinema

Fennell isn’t breaking ranks. Several of the most-watched versions foreground only the first generation. William Wyler’s 1939 classic, which stops with Cathy’s death, earned multiple Academy Award nominations and remains the benchmark for Hollywood’s take on the novel. Andrea Arnold’s 2011 film likewise eschews the later chapters to pursue a raw, elemental portrait of Cathy and Heathcliff’s early bond. Truncation can be an artistic choice, not a capitulation—an invitation to study the wound rather than its aftershocks.

Thematic Payoff Without the Shovel in the Graveyard

By staying in the first half, Fennell still delivers the book’s core tensions: consuming attachment, social climbing, and the violence of class boundaries. Cathy’s courtship of the Lintons mirrors Saltburn’s fascination with entry into elite circles, while the film’s manor-house spectacle echoes Brontë’s architecture of power. The obsessive energies that will one day lead Heathcliff back to the grave are present in the performances and the mise-en-scène, not in literal exhumation.

Adaptation as Interpretation, Not a Literal Inventory

Adaptation scholars like Linda Hutcheon have long argued that fidelity to a source is less important than clarity of perspective. Fennell’s perspective is unmistakable: center adolescent intensity, sharpen the class critique, and resist the easy shock she has already mastered. The absence of the grave scene isn’t timidity; it’s a way to let Brontë’s themes breathe, unclouded by a single, sensational image.

The result reframes Wuthering Heights for a new audience: not as a compendium of Gothic set pieces, but as a concentrated study of how love curdles into possession—and how the moors themselves seem to remember every choice left buried.