Elon Musk says he needs a pay plan that could amount to $1 trillion in compensation for him not to cash out, but rather to keep his grip on what he acknowledges could be Tesla’s future “robot army.” Musk recently framed the eye-popping number in a quarterly earnings call as a governance tool, suggesting that guiding an enormous fleet of AI-enabled machines requires the kind of voting power you can’t take away.

The request immediately reignited debate about executive power at Tesla. A coalition of unions and corporate watchdogs has organized under the Take Back Tesla banner to resist the package, arguing it is excessive and risky. Musk argues that extraordinary AI ambitions require extraordinary alignment — especially if Tesla upsells humanoid robots and autonomous systems that could dwarf the car business.

Musk Ties Pay to a Robot Workforce: Why?

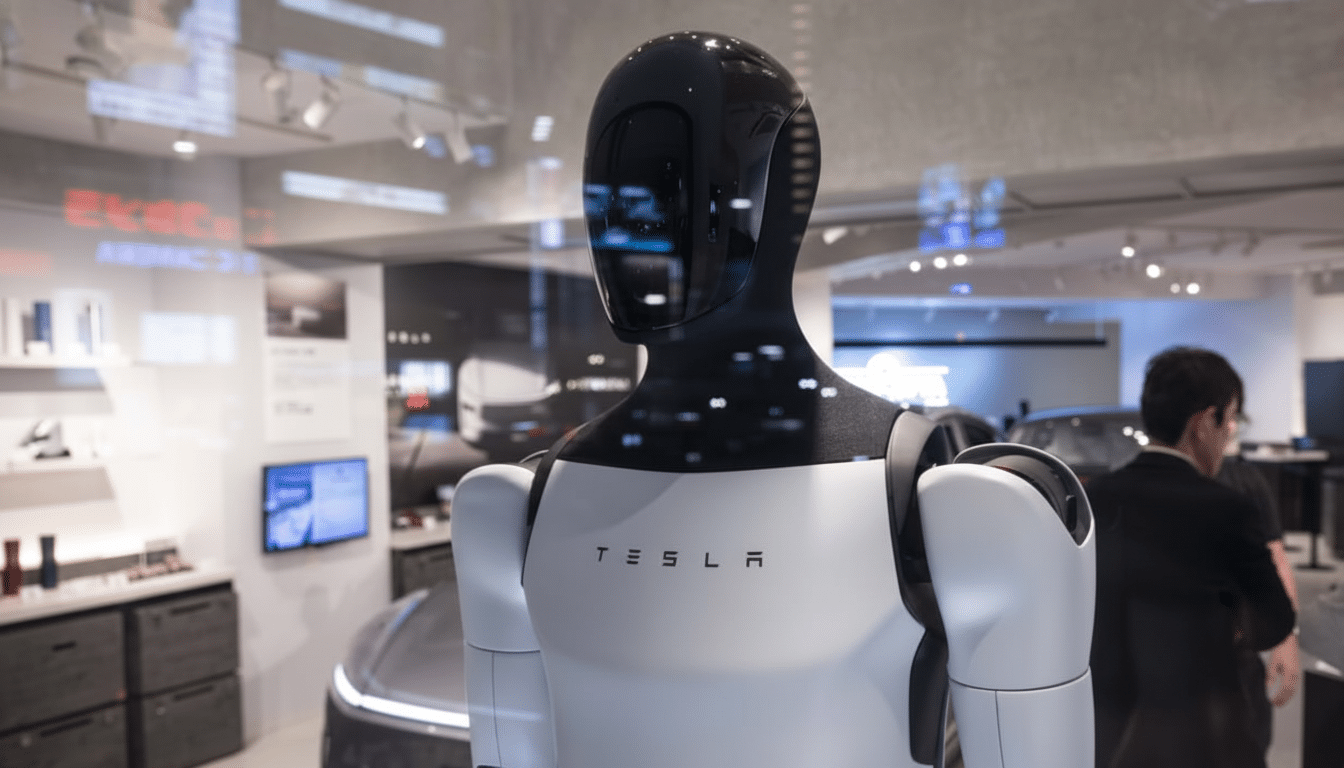

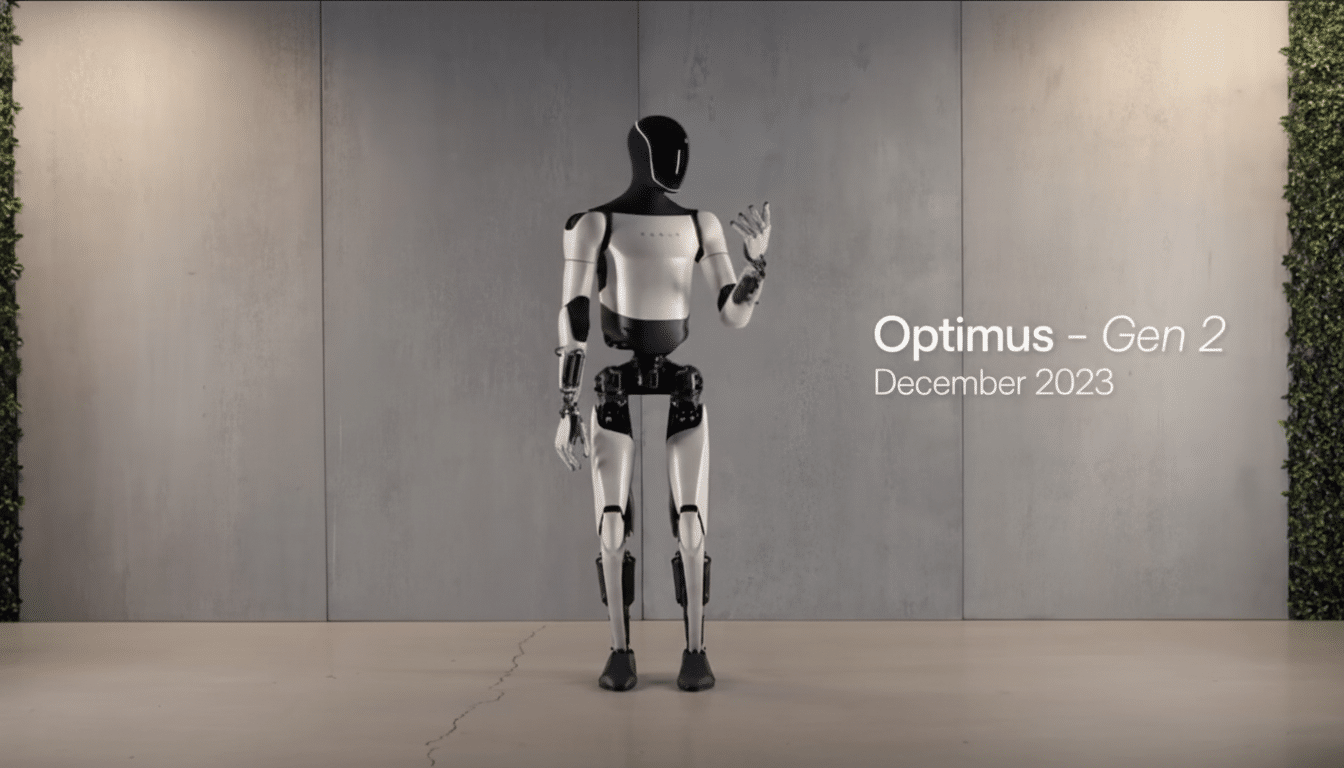

Tesla’s sales pitch on robotics focuses on Optimus, which is a humanoid platform and one that Musk has said could perform repetitive factory work — and eventually chores in homes. On top of that are innovations around robotaxi development and factory automation built on the back of Tesla’s homegrown AI stack, data engine, and custom training infrastructure like its supercomputer system, Dojo. Musk has said again and again that these projects could become Tesla’s most valuable products.

His case for outsized control is simple: If Tesla builds an enormous networked fleet of intelligent machines, he doesn’t want the voting power to be in some other person’s hands, should a future board or coalition of shareholders want to oust him from the company and change course. Musk has indicated in the past that he wants about 25 percent of the company’s voting power in order to feel comfortable overseeing Tesla’s AI direction — a threshold that, to his way of thinking, maps incentives with the scale of the bet.

What a Trillion-Dollar Package Does and Doesn’t Mean

The headline number is the amount that the CEO could receive from performance-based stock awards, not cash. Such plans are usually based on ambitious targets around market value, revenue, profit, or product release. If Tesla manages to achieve those goals over time, the grant could become worth nearly $1 trillion at higher valuations; if not, it becomes all but worthless.

At the same time, its scale brings to the fore classic issues about governance. Those huge option grants can dilute other shareholders, and they concentrate power in a single executive for years. Proxy advisers such as ISS and Glass Lewis have traditionally tended to highlight outsized awards and weak performance gates. The debate also comes in the wake of high-profile scrutiny of an earlier Tesla pay package in the Delaware Court of Chancery, which shed light on process, independence, and disclosure standards for mega-grants.

How Large Could Tesla’s So-Called ‘Robot Army’ Be?

It is difficult to overstate the scale. The International Federation of Robotics recently said that industrial robot installations hit an all-time high, surpassing 500,000 units in new installations globally — with the world’s robot stock now somewhere in the millions. Even a single company deploying humanoids at commercial volumes would be unprecedented: All of dexterity, cost, safety, and autonomy as well as massive manufacturing capacity would need to align.

Tesla, for its part, counters that it has the edge when it comes to data and integration: billions of real-world driving miles feeding perception models, vertically integrated hardware and software, and the ability to train at scale. The company has also indicated that it will spend billions of dollars on AI compute in order to speed training cycles. If Optimus can do useful work at an attractive cost per hour, factory trials could be extended to logistics centers, retail backrooms, and maintenance activities at facilities — a service robot market that analysts say will grow rapidly in the years ahead with labor bottlenecks unlikely to go away.

Safety, Accountability, and Control in AI Robotics

“Robot army” is branding hyperbole, but it highlights genuinely hard questions about risk management. For humanoids and autonomous fleets, they need to be guarded very strictly: fail-safe actuation, tamper-proofing, and monitoring according to standards like ISO 10218 or ISO/TS 15066 for collaborative robots. On the roads, where automated driving systems are on public highways, NHTSA oversight will be crucial; in the workplace, OSHA and product liability frameworks may also come into play.

Centralized leadership can make decisions more quickly as a company races on AI, but investors also push for checks and balances. Advocacy groups like the Council of Institutional Investors have long contended that mixing excess pay with outsize voting power can undermine board independence and dampen shareholder input. On balance, the central Tesla debate is whether the strategic pros of a single durable guiding hand outweigh those governance cons.

What Shareholders Must Decide About Tesla’s Future

Shareholders are not just voting with a number here; they are voting on the theory of how to build and own an AI-empowered hardware network at planetary scale. If the Optimus, robotaxis, and factory automation seem like enough to justify valuing Tesla roughly seven times more than it is today, they might be willing to swallow a deal tailored effectively to ensure Musk remains firmly in control. If they find the award aggressive, they will pull for stronger performance hurdles, sunset provisions, or structures that share the dilution while preserving the incentive.

The result will amount to a signal about how the market wishes to regulate the next stage of AI as a concentrated founder-led bet or as a more distributed, board-first model. Either way, the word “robot army” has shoved us into a frank conversation about power: who gets it, how they get it, and what guardrails we should have around machines that are doing much more alongside us.