Elon Musk is reportedly pitching one of his boldest space ideas yet: a lunar factory paired with a giant electromagnetic catapult to fling satellites off the Moon and into space. According to The New York Times, the concept would serve xAI’s push to power artificial intelligence with orbital data centers, a plan now intertwined with SpaceX following a corporate merger reported by the outlet.

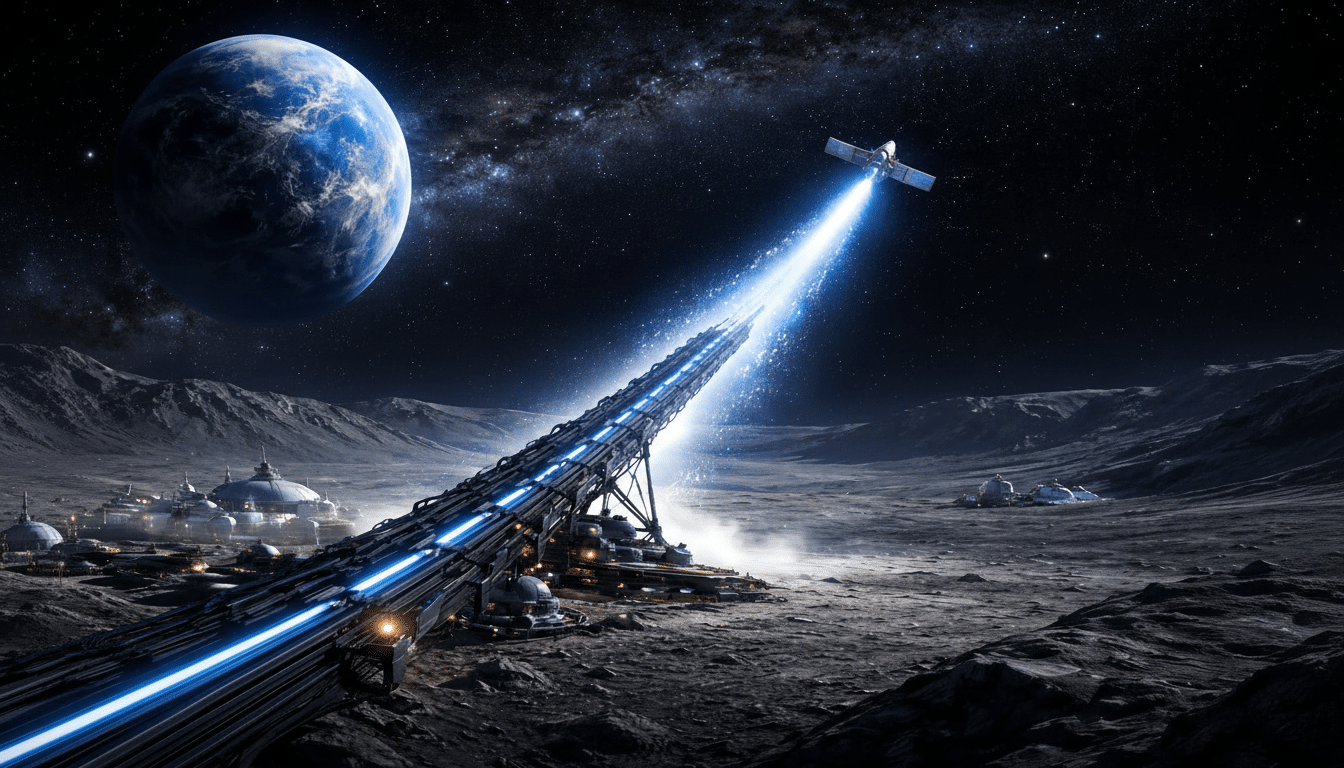

The “catapult” in question is a mass driver—an electric launch rail that uses magnetic fields to accelerate payloads to orbital speeds. It’s a sci-fi staple with serious pedigree in aerospace research, and the Moon is the most forgiving place in the neighborhood to try it: no atmosphere, roughly one-sixth Earth’s gravity, and a lower escape velocity of about 2.38 km/s.

What a Lunar Mass Driver Would Do in Practice

A lunar mass driver would function like a railgun for cargo. Superconducting coils or linear motors accelerate a payload along a long, carefully aligned track, culminating in a precise release that sends the package on a ballistic arc to lunar orbit or beyond. Unlike rockets, the “engine” stays on the ground and can fire repeatedly with only electrical input and maintenance.

In practice, such a system could launch modular components—ruggedized electronics, radiators, structural trusses, propellant tanks—to assembly nodes in cislunar space, where larger satellites are built robotically. For fragile hardware, mass drivers use shock-isolating “sabots” and longer tracks to keep g-forces within survivable limits. The Moon’s vacuum removes aerodynamic heating from the equation, but precise timing and guidance thrusters are still needed to circularize orbits after launch.

The physics are straightforward but unforgiving. To reach 2.4 km/s using a 10 km track, the average acceleration is roughly 29 g; over 2 km, it jumps near 150 g. That argues for very long rails, robust packaging, or a hybrid approach where the driver supplies most of the delta-v and small onboard engines finish insertion. On the upside, the energy per shot is manageable for cargo. Accelerating 100 kg to 2.4 km/s requires around 288 MJ of kinetic energy; with system losses, call it several hundred megajoules delivered in pulses—a challenge, but not a showstopper with megawatt-scale power and storage.

Engineering Hurdles And Physics Realities

The most immediate obstacles are construction, power, and dust. Building a multi-kilometer precision structure on the Moon demands heavy logistics, regolith handling, and autonomous assembly. NASA and academic studies dating to Gerard O’Neill’s Princeton work outlined electromagnetic launchers for lunar mining, but translating paper designs into a durable, thermally stable, cryogenically cooled system on a body with wild day-night temperature swings is a different league.

Power is another gating item. A high-rate launcher needs steady megawatts. That implies large solar farms with energy storage for the lunar night or compact fission reactors—the kind of infrastructure agencies like NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy have been prototyping at tens of kilowatts and aspiring to scale. Thermal rejection for both the launcher and satellite assembly also requires expansive radiators and dust mitigation.

Lunar dust itself is notorious. It’s abrasive, electrostatically clingy, and a hazard to optics, seals, and bearings. Firing material off the surface risks ejecta plumes that could sandblast nearby assets or even contaminate distant sites if not contained. Expect engineered berms, shields, and carefully chosen firing azimuths to keep debris out of harm’s way, as well as international coordination so trajectories don’t endanger other missions.

There is relevant experience to draw on. SpinLaunch has demonstrated ground-based kinetic launches at suborbital speeds, and electromagnetic railguns have validated high-speed pulsed-power systems in defense research. Both point to the feasibility of core subsystems even if the lunar environment adds novel constraints.

Why Build AI Infrastructure Off Earth and in Orbit

The commercial logic behind off-planet data centers is straightforward: abundant sunlight, vast thermal radiators, and isolation from terrestrial siting and permitting constraints. The solar constant in space is about 1,361 W/m² with no clouds, offering predictable power for very large arrays. In parallel, global data centers already consume an estimated 1–1.5% of electricity according to the International Energy Agency, and AI workloads are pushing energy and cooling demands even higher. Orbiting compute farms could, in theory, scale without competing with terrestrial grids, beaming results to Earth and networking through inter-satellite links.

Still, latency, maintenance, and debris risk complicate the picture. Servicing requires robotics and on-orbit spares. Spectrum coordination, ITU filings, and cybersecurity enter the critical path. And while the Moon is an attractive manufacturing site for its low gravity, assembling high-value satellites off-world presumes mature in-space manufacturing and reliable heavy lift to bootstrap the infrastructure. That is where SpaceX’s Starship ambitions intersect with xAI’s compute goals.

What to Watch Next as Lunar Catapult Plans Evolve

Near term, look for proof-of-concept steps rather than a full-fat lunar factory. A credible sequence would include a ground demonstrator for a long-rail electromagnetic launcher, a robotic lunar materials pilot to qualify regolith handling and dust control, and a small-scale mass driver firing inert loads to a capture vehicle in low lunar orbit. Parallel efforts would target megawatt-class surface power and autonomous assembly tech, ideally aligned with broader Artemis architecture and the international norms set by the Artemis Accords.

Musk’s track record shows a willingness to chase audacious ideas and occasionally make them routine. A lunar mass driver is at the far end of that spectrum—ambitious, risky, but within the realm of physics. Until detailed designs, partners, and timelines emerge, it remains an aspiration. If the pieces do start falling into place, it would mark a profound shift in how humanity builds and launches hardware beyond Earth.