Electroflow claims it can make lithium iron phosphate cathode material for about 40% less than top Chinese producers, a bold assertion in a market where chemistry and supply chains determine who comes ahead on cost. The startup’s pitch: a small, electricity-operated facility that eliminates many steps in lithium processing and turns brine into battery-grade LFP with fewer inputs, less energy use and less distance between American car companies and their batteries.

Why falling LFP costs matter for EVs and energy storage

It has since become the budget workhorse of the EV world for its robustness, thermal stability and the fact that it doesn’t have nickel or cobalt in it. Car manufacturers rely on it for standard-range models and energy storage systems, which drives demand up and puts pressure on suppliers to maintain low prices. LFP cathode active material from China is at around $4,000 per metric ton on a standard basis, and it’s a price that U.S. consumers have absolutely been unable to match once you take account of tariffs, logistics and higher domestic processing costs.

- Why falling LFP costs matter for EVs and energy storage

- How Electroflow’s three-stage LFP process actually works

- Price claims and market benchmarks for LFP cathodes

- Scaling challenges, energy use and Electroflow’s footprint

- Policy shifts and supply chain implications for U.S. LFP

- What to watch next as Electroflow scales LFP production

Cheaper LFP reverberates across the bill of materials. On a typical midsize pack, just taking a few dollars per kilogram out of the cathode material can result in hundreds of dollars in savings per vehicle. That is why producers from BYD to CATL have scaled as aggressively as they have, and why American automakers are looking for credible non-Chinese supply that does not blow up the sticker price.

How Electroflow’s three-stage LFP process actually works

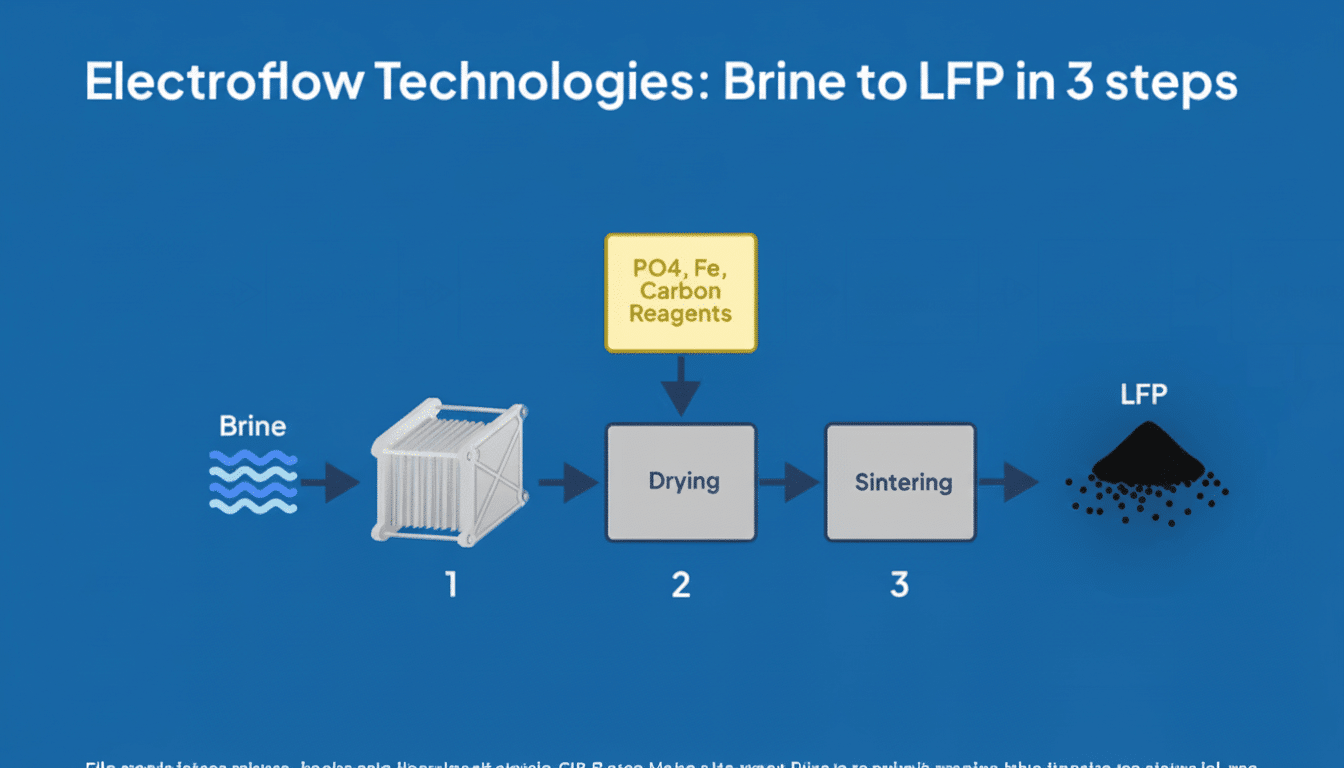

The heart of Electroflow is a type of electrochemical cell that operates like a battery but runs in reverse half the time. Engineered anodes pluck lithium ions straight out of brine; reverse the current, and those ions slip back into a carbonate solution. The output is lithium carbonate, which then combines with iron and phosphate to create LFP powder. As a three-stage process, the company hopes to avoid several of the thermal and chemical steps used in traditional refining.

The company has demonstrated that the system works with geothermal brines, a particularly challenging feedstock given its variable chemistry and impurities, harvested from a site in California. The entire module is built to be transported inside a 20-foot shipping container so that operators can place them at the source of brine and save on transport costs. One container-scale unit from Electroflow will go after approximately 100 metric tons of LFP production per year.

Power consumption is a critical descriptor as the process is entirely electrical. Electroflow estimates that generating approximately 50 metric tons of lithium carbonate a year would require about as much electricity as an average U.S. home uses, with most of the water in the process recycled. If the profile proves to hold at scale, that would be an uncommonly light footprint in both energy and water compared to traditional evaporation or high-temperature routes.

Price claims and market benchmarks for LFP cathodes

Electroflow’s first production target, “V1,” sets the cost at or close to $5,000 per metric ton of material, with a roadmap below $2,500 as systems scale. For reference, you’ll hear analysts often refer to China’s cost advantage as a function of integration: plentiful midstream capacity enables the maturity of precursor supply and asset base amortization through huge volumes. Both Benchmark Mineral Intelligence and BloombergNEF have noted how those factors, combined with policy support for high-quality LFP production and clustering effects, ensure Chinese LFP pricing remains structurally low.

Domestically undercutting that price floor could be quite the accomplishment. If Electroflow’s sub-$2,500 per ton goal stands up in commercial rather than just pilot-run conditions, it would bring LFP made in the U.S. within arm’s reach of the lowest-priced global supply already before any policy incentives were factored in. It would also ease the pressure from currency fluctuations, shipping costs and trade frictions that can cloud procurement plans.

Scaling challenges, energy use and Electroflow’s footprint

But the technical leap is just half of the story, with manufacturing repeatability and uptime being the other half. Electrochemical systems for lithium recovery from complex brines need to be resistant against fouling, able to control selectivity and deliver performance over extended duty cycles. Independent confirmation on various brine chemistries — geothermal, oilfield and sedimentary — will be essential. Companies developing direct lithium extraction have found that impurity management and membrane durability can either make or break the economics.

Capex per ton is a second swing factor. Containerized systems can have linear up-scaling, but project finance favors large de-risked trains. If Electroflow can mass-produce its cell stacks and balance-of-plant cheaply, it could escape the “pilot-prototype plateau” that ensnares many clean-tech processes between lab success and bankable commercial plants.

Policy shifts and supply chain implications for U.S. LFP

Policy winds are at Electroflow’s back. The rules on domestic battery content and the foreign-entity-of-concern limitations are nudging automakers to localize cathode supply. The advanced manufacturing production tax credit lowers the effective cost of producing battery ingredients in America, and federal as well as state programs are funneling money into critical mineral projects. Meantime, the rise of brine resources — from California’s geothermal deposits that some are calling “Lithium Valley” to projects in Arkansas powered by major energy players — promises feedstock close at hand if the refining can be done cost-effectively.

A U.S.-based LFP source also would be a diversity play in the market, which has been dominated by a handful of heavyweights from China over the past decade.

It might also offer cell makers and pack integrators an option in the middle with standard-range EVs and stationary storage, where LFP’s cycle life and safety are a selling point.

What to watch next as Electroflow scales LFP production

Three proofs will decide if the 40% production cost claim sticks:

- Third-party audits of production cost at meaningful volumes

- Long-duration runs on variable brines with stable purity specs

- Offtake agreements with cell or pack makers that depend on reliable LFP performance

Lifecycle assessments and water and power intensity will also be important as buyers consider upstream emissions.

On paper, Electroflow’s approach is elegant: simplify steps, electrify chemistry, containerize production. If the company can convert that at all into bankable plants, it would not only close the cost gap with China — it would reset assumptions about how quickly domestic LFP capacity scales and how cheaply.