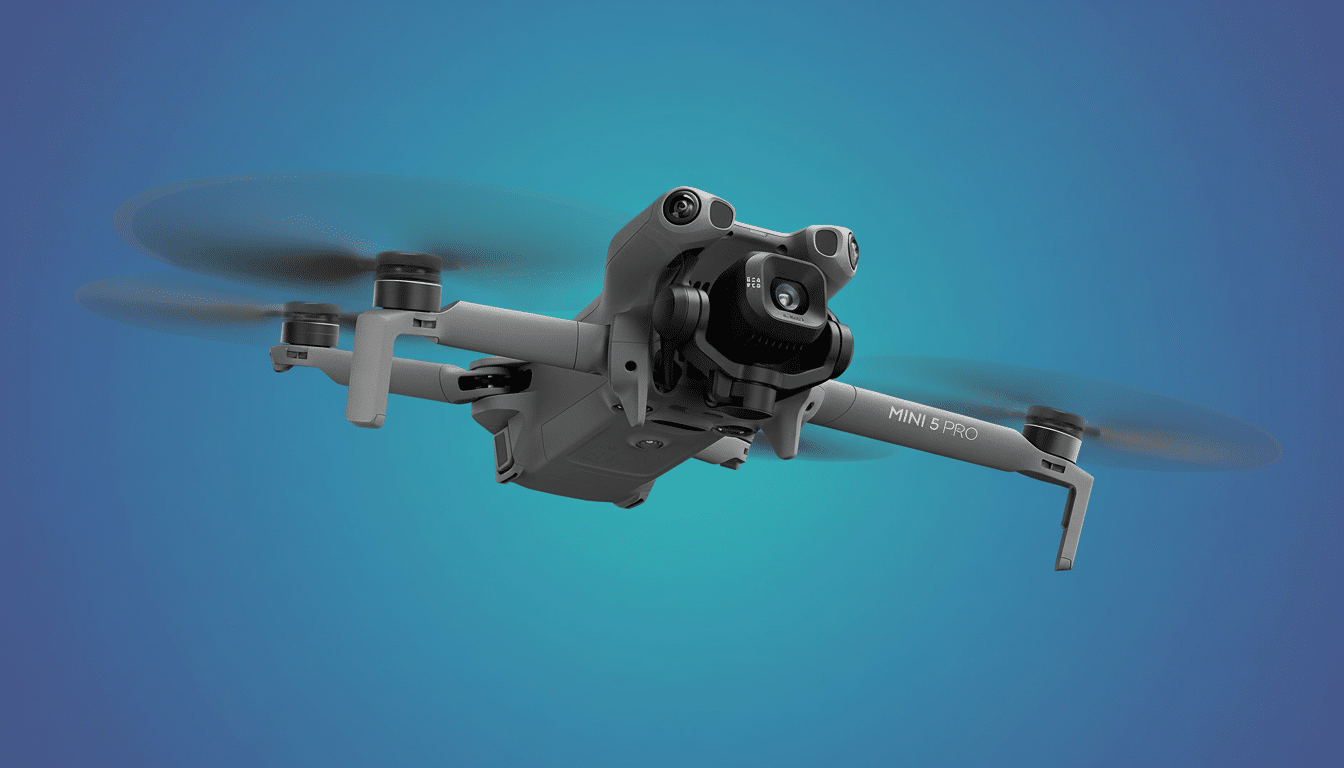

DJI’s Mini 5 Pro is the most ambitious sub-250g drone yet, combining a 50MP Type 1 image sensor with smarter obstacle avoidance that—at last—includes LiDAR to see more clearly in dim conditions. It is, on paper, the pocket aircraft manufacturers have been pleading for. In practice, Americans can’t buy it through official channels—another high-profile DJI launch landing everywhere except the United States (although you can find it from third-party sellers).

A Stunningly Tiny Mini With Big-Camera Aspirations

The Mini 5 Pro maintains a maximum takeoff weight of 249g—below the well-known 250g threshold in most countries that reduces friction and supervision for recreational flyers. The camera is the standout: a 50MP Type 1 (one-inch type) sensor that’s around 65% larger than the 1/1.3-inch chips we’re used to seeing in this sort of class, promising cleaner low-light and more generous dynamic range.

Content creators gain 4K60 HDR recording, a 3-axis gimbal that doubles as a selfie camera and can flip 180 degrees for true viewing without obstruction, and a series of smart shot modes with an ingenious AI Director to act as your personal movie crew.

DJI also adds a safety net to that flight-path memory, letting the aircraft retrace its steps if it loses reliable satellite lock.

It’s damn robust for such a tiny airframe. In the standard pack, DJI estimates up to 36 minutes of flight time and as much as 52 minutes with an optional extended battery, adding more filming time for solo shooters waiting for a perfect window of light. Real tools in a travel-friendly shell—that’s the recipe that made the Mini line such a monster hit.

The U.S. Absence Is About Policy, Not Pixels

So why no US launch? In short, policy headwinds. The US Customs and Border Protection has recently begun to monitor more closely the imports of specific Chinese-manufactured electronics under the enforcement of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. Though DJI is not on the UFLPA Entity List, detentions can happen if goods are suspected of violating the law’s supply-chain provisions. DJI has said its products are made in Shenzhen and denied using forced labor.

In a separate development, DJI is still on the Department of Commerce Entity List, which controls access to certain US-origin technologies. The listing isn’t a ban on retail, but it complicates operations and has fueled a wider national security debate around foreign-made imaging gear and communication devices.

That debate is now linked to a federally mandated security review of DJI and some other brands’ “communications or video surveillance equipment.” If regulators determine that the products create too great a risk, they can be added to the FCC’s Covered List—a step that in the past has led to diminished US sales and authorizations for impacted equipment. It’s as yet unclear exactly what the outcome, not to mention timing, of that audit will be, industry sources say.

Meanwhile, there is real import friction. US creators have reported drones being held for weeks or months every time they are returned from the manufacturer after repair—even when those repairs were conducted overseas. For a working videographer, the grounded or delayed aircraft is not an inconvenience; it’s billable days gone.

The Market Impact Without DJI’s Leading Mini

The void of a DJI listing on Wall Street is no little tremor. DJI has long been the dominant player in both the consumer and prosumer segments, with global share frequently estimated to be north of 70%, according to Drone Industry Insights. When the category leader is MIA in the US, those upgrade cycles can go stagnant, and creators either try to import at risk or limp along with older gear.

There are alternatives, but parity is hard to come by. Some makers are concentrating more on enterprise and public safety, others throwing anything to a wall in experimental projects based around 360-degree concepts without any real cinematic strategy or quality. Several US and European brands have entered the game with solid airframes, but a truly stable image pipeline, reliable autonomy, and robust ecosystems—ND filters, batteries, controller options (and customizability), firmware cadence—is where DJI has historically set itself apart.

For real-estate shooters, travel filmmakers, and documentary units who need to avoid permitting paperwork by working with sub-250g drones, the Mini 5 Pro’s balance of one-inch-type imaging, vertical capture, and longer flight time would meaningfully elevate production value.

Its absence can force teams to go out and rent bigger craft, reconsider what’s on their shot list, or cut aerial sequences entirely from a production.

Regulatory Clarity and a Realistic Path Forward

Two things might alter the course: a federal audit completed with clear results that are released publicly, and more clarity from CBP about how importers can show they have compliant supply chains under UFLPA. DJI has publicly embraced scrutiny (the company also insists it’s still committed to the US market).

It’s important to separate issues. FAA regulations and Remote ID compliance determine how drones can be used in US airspace, but they haven’t specifically targeted DJI’s consumer models. The sales and import questions arise from supply-chain enforcement efforts and national security assessments. Until then, DJI’s most sophisticated Mini will still officially be off-limits to American buyers.

The irony is hard to miss: a revolutionary camera drone that can fly just about anywhere but can’t find an easy runway into the biggest content market on earth. Meanwhile, foreign creators savor the jump ahead for now. US pilots are biding their time as policy lags behind technology.

References cited:

- US Customs and Border Protection posts on UFLPA enforcement

- Commerce Entity List additions

- The FCC Covered List process

- FAA small UAS registration guidance

- Market-share analyses from Drone Industry Insights

- Reporting by human rights organizations about forced labor concerns in Xinjiang