DJI is contesting the Pentagon’s characterization of the drone company as a “Chinese military company,” appealing after a federal district court refused to annul it. The case is a test of how the U.S. government uses national security designations to control access to dual‑use technologies, and how companies can challenge such designations under administrative law.

What the Pentagon Designation Means for DJI

Under Section 1260H of the National Defense Authorization Act, which calls for a list of “Chinese military companies,” the Pentagon maintains a Department of Defense list that it updates. In fact, inclusion doesn’t amount to a blanket ban on sales, but its presence carries weight: federal agencies and state governments reference it when they set procurement policies, investors ratchet up risk screening, and partners may walk away to avoid reputational exposure.

DJI has also been subject to separate U.S. actions. The Commerce Department added the firm to its Entity List, citing human rights concerns, effectively blocking it from receiving certain U.S. components and technology. A number of federal agencies have ceased purchasing Chinese-made drones, and legislation has been proposed to add certain drone manufacturers to the Federal Communications Commission’s Covered List, which prevents new equipment authorizations in the United States.

DJI’s Argument on Civilian Use and Dual-Use Claims

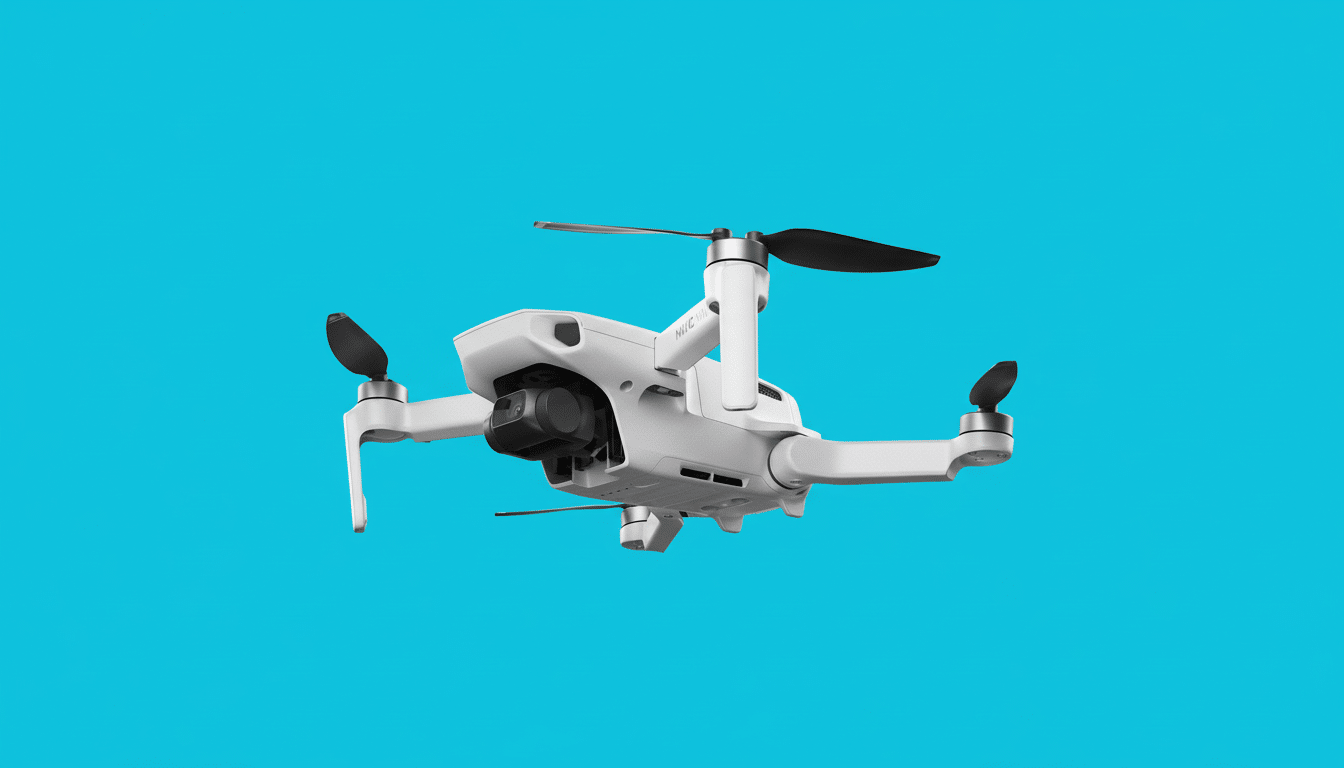

DJI says it designs and sells products for civilian markets and “does not create or market weapons.” The company insists it is privately run and denies allegations of government control. It has also insisted that it would not support weaponization, as seen in geofencing and in tools for remote identification meant to enhance safety, and has suspended business in conflict zones where it suspected consumer drones were being used as attack tools.

In challenging the designation, DJI contends that the Pentagon’s justification is based on small drones’ dual‑use potential rather than evidence of military ties. Commercial technologies—things like navigation modules or imaging sensors—can be switched to the battlefield, company representatives say. As an example of the challenge in real‑world terms, the European Union has restricted exports to Russia of items such as a particular type of gaming controller because they can be repurposed for use in piloting improvised drones.

That has caused some enterprise and public safety customers to slow down or end business operations, DJI says, even as the firm maintains that it forbids distributors and resellers from knowingly selling for military end use. The district court disagreed, holding that the Department of Defense had an adequate administrative record to support its position in light of the strategic importance of small uncrewed aircraft in modern conflicts.

Inside the Legal Fight Over the Pentagon Classification

The appeal will center on administrative law standards: whether the Pentagon’s designation was based on substantial evidence and whether the agency acted arbitrarily or capriciously. Courts, legal experts say, generally yield to national security agencies on classification decisions but insist on a reasoned justification and, flawed as it may be, a record that draws links between facts and conclusions.

DJI will likely make two central arguments.

- The government has failed to demonstrate ownership, control, or direction by the Chinese military or state.

- To call a company out on the potential military use of its civilian products is a slippery slope that threatens to pull in far more dual‑use manufacturers.

The government is likely to counter that China’s military‑civil fusion strategy obfuscates distinctions between civil and defense industrial bases, justifying the designation.

Why the Outcome Matters for Agencies and Markets

DJI is the world’s leading small drone maker. Industry studies from DroneAnalyst and other research firms have consistently positioned the company at or above 70 percent share of consumer sales, and as the largest supplier to U.S. first responders. DRONERESPONDERS’ surveys suggest that the vast majority of public safety departments use DJI products for search and rescue, fire scene mapping, disaster response, and other missions due to cost, reliability, and depth of ecosystem.

A prolonged “military company” designation could speed up a move toward non‑Chinese vendors in government contracting and encourage rival domestic products. Some states already have limitations on purchases of foreign‑made drones for public agencies. Yet an abrupt shift could leave current fleets and training investments stranded. Analysts at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and RAND have cautioned that policy should weigh security fears against operational requirements, as well as realities of global supply chains.

Supply frictions have added pressure. Importers say that U.S. Customs and Border Protection has held shipments of electronics in several sectors under the purview of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, and industry groups have reported that drone parts are part of that tally. DJI has also denied using forced labor and said it has improved documentation and supplier audits to comply with U.S. checks.

What to Watch Next in the DJI Military Label Appeal

The appeals court’s decision could shed light on how agencies need to document and explain designations related to dual‑use tech and military‑civil fusion. It may also pressure parallel policy tracks such as federal procurement rules, FCC equipment authorization debates, and state-level restrictions.

For public safety agencies, utilities, and enterprise operators, the near‑term questions are practical:

- Whether existing DJI fleets can remain serviced

- How warranty and parts availability could be impacted

- What competitive alternatives cost

For investors and suppliers, the case serves as a barometer for how deep U.S. national security policy will penetrate commercial markets for technology where civilian and military uses are increasingly overlapping.