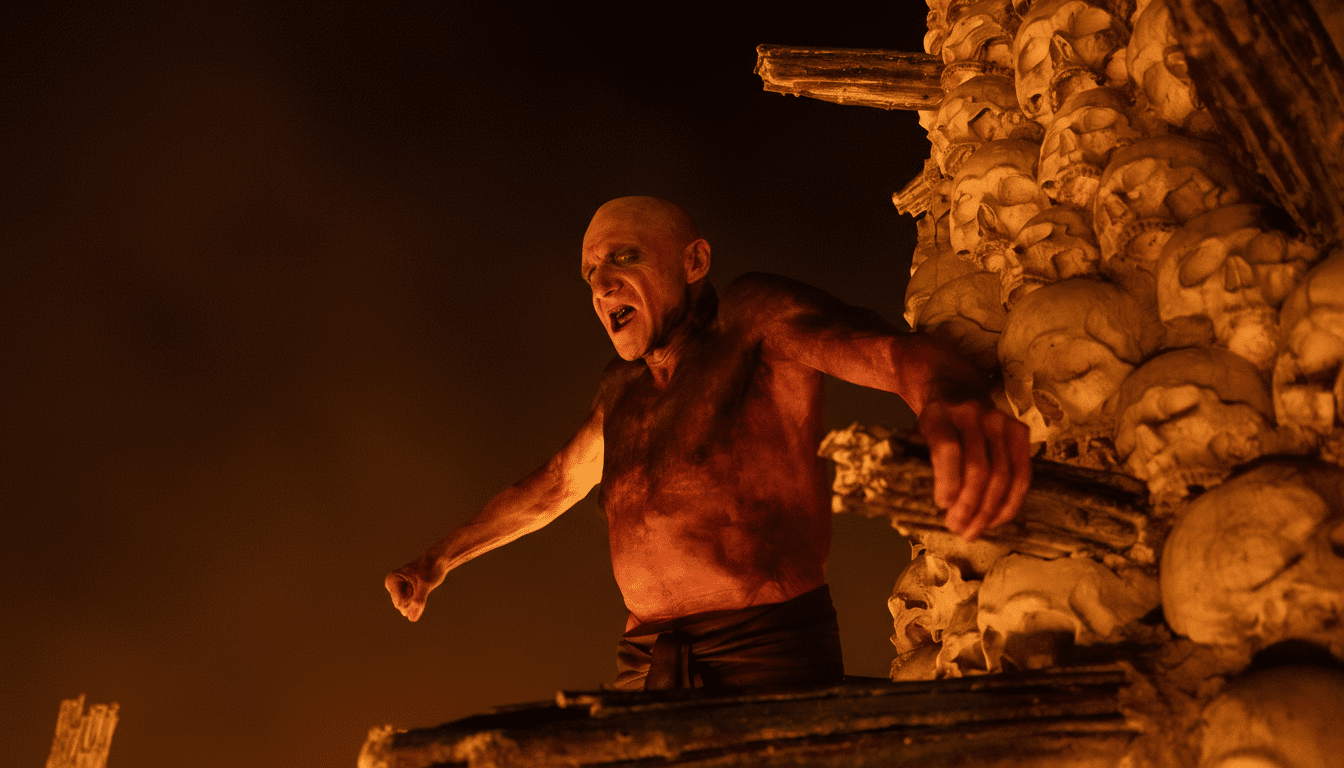

Director Nia DaCosta and actor Jack O’Connell are pulling back the curtain on the showstopping “Bone Temple” sequence from 28 Years Later, a delirious, fire-lit set piece built around Iron Maiden’s The Number of the Beast and a fearless, full-bodied turn by Ralph Fiennes. What reads on paper like a high-wire gamble plays on screen as an ecstatic, metal-infused exorcism that jolts both the characters and the audience.

Inside The Fire And Choreography Behind The Sequence

DaCosta says the moment was conceived in Alex Garland’s script, but it only ignited when every department locked in: choreography by Shelley Maxwell, production and costume design led by Carson McColl and Gareth Pugh, and a practical ring-of-fire that turned the set into a crucible. O’Connell recalls the night they watched the full run with stunts and pyrotechnics as a collective crescendo, describing the effect as almost hallucinatory from the pit where his character, Jimmy Crystal, stands in awe.

The shot design leans into physical reality. Fiennes—near-nude, iodine-stained, and wielding fire—had to repeat the performance for hours. That demand shaped the coverage: sustained takes to preserve momentum, intercut with tight reaction shots from O’Connell and the “Fingers,” whose faces become the scene’s emotional barometer.

Why Iron Maiden’s The Number Of The Beast Powers The Scene

In the story, Fiennes’s Dr. Ian Kelson impersonates a satanic figure to outwit a gang, dropping a needle on a hand-cranked player and unleashing The Number of the Beast—an anthem built for ritual. The gallop, chanted refrains, and hellfire imagery fuse with Kelson’s DIY stagecraft to sell the con. It lands because the Fingers have never seen a rock show; the spectacle becomes a cultural thunderclap in a world where music venues have vanished.

The choice also taps a well-documented phenomenon: legacy rock surges when tethered to vivid screen moments. Billboard and Luminate have tracked catalog songs skyrocketing after buzzy placements, from Queen returning to the Hot 100 after Wayne’s World to Metallica’s renewed chart life post–Stranger Things. Here, Maiden’s classic does more than needle-drop—it becomes character, world-building, and plot engine.

From Page To Picture: How The Sequence Found Its Power

DaCosta admits the scene looked perilous in early read-throughs: too grand to fake, too odd to half-commit. The solution was process. Once rehearsals synced Maxwell’s movement language with Pugh’s ritual-costume silhouettes and McColl’s bone-laden architecture, the number cohered. Editor Jake Roberts—an Oscar nominee for Hell or High Water—cut the performance to ride Fiennes’s stamina while preserving the hypnotic build, sending early assemblies that reassured the team they had something electric.

The result frames Fiennes not as a lip-syncing mimic but as a conductor. Flames circle, shadows strobe off the ossuary walls, and the camera returns, again and again, to O’Connell’s Jimmy—first skeptical, then transfixed—as the music drills through the Bones’ mythos and into his authority.

The Risk And The Safety Net Behind The Fiery Set Piece

Practical fire on a crowded set requires choreography beyond dance. Productions typically coordinate with licensed pyrotechnicians, enforce heat and distance metrics, and rehearse extinguisher and egress plans in line with guild and insurer protocols. UK crews often reference Health and Safety Executive guidance for special effects; the team here balanced the infernal look with a repeatable, safe cadence so Fiennes could push physically without crossing risk thresholds.

Securing the track is its own high-wire act. Major-catalog syncs like Iron Maiden’s are known in the industry to command significant fees and approvals from rights holders and management. Aligning narrative intent with artist brand is crucial; when the fit clicks, the payoff can be cultural rather than merely musical.

Why It Resonates With Audiences During Early Screenings

Early screenings suggest the sequence earns mid-film applause—the rare diegetic performance that operates like a live gig. It’s not just the flames or the song; it’s the counterpoint between Fiennes’s possessed composure and the shell-shocked spectators. Film history offers precedents for crowd-igniting musical turns, but Bone Temple’s spin is its apocalypse-baroque design: bones for trusses, iodine for paint, a turntable for a temple.

For DaCosta, the triumph lies in collaboration. For O’Connell, it’s the privilege of reacting to a co-star detonating a room without a single line of dialogue. For audiences, it’s proof that even in a world of scarcity, cinema can still go big—full volume, full flame, and fully earned.