NASA’s Curiosity rover has begun a rare wet-chemistry experiment inside Gale Crater, using its final reserve of a special solvent to search for life-related organic material in Martian rock. The test, carried out on powder from a drill site nicknamed Nevado Sajama, is designed to reveal complex carbon-bearing compounds that standard heating methods often miss.

Why This Experiment Is Rare and Scientifically Valuable

Curiosity carried only two tiny cups of tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) in methanol for its entire mission, making each opportunity to deploy the solvent exceptionally valuable. The rover used the first cup in 2020 at a site called Mary Anning; the results broadened the palette of detected organics compared with routine pyrolysis, but also underscored how tricky it is to distinguish Martian organics from compounds generated within the instrument itself.

- Why This Experiment Is Rare and Scientifically Valuable

- How the Three-Stage Test Works Inside Curiosity’s Lab

- A Promising Target in Gale Crater’s Boxwork Terrain

- What Scientists Hope to Learn from Curiosity’s Test

- Key Numbers Behind This Milestone in Curiosity’s Mission

- What Comes Next for Curiosity’s Search for Organics

Mission planners across NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Goddard Space Flight Center rehearsed the sample handoff and analysis steps to avoid missteps, a necessity when a one-time consumable is on the line. Out of the rover’s 74 sample cups, nine were built for “wet chemistry” at landing. With TMAH now exhausted after this run, Curiosity still retains other derivatization reagents, including MTBSTFA, for future studies.

How the Three-Stage Test Works Inside Curiosity’s Lab

TMAH acts as a chemical liberator and tag for organics, helping unbind and stabilize fragile or large molecules so the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument can separate and identify them. After the 2020 trial, researchers at Goddard redesigned the procedure into a three-stage, temperature-stepped workflow to better mimic Earth-based lab protocols and minimize confounding reactions between the solvent and Martian sediments.

Curiosity has already executed two of the three steps, with the solvent interacting with the powdered sample at progressively higher temperatures. Interpreting the resulting chromatograms and mass spectra will take time; the team expects to spend months validating signals, cross-checking blanks, and comparing against laboratory testbed runs before drawing conclusions.

A Promising Target in Gale Crater’s Boxwork Terrain

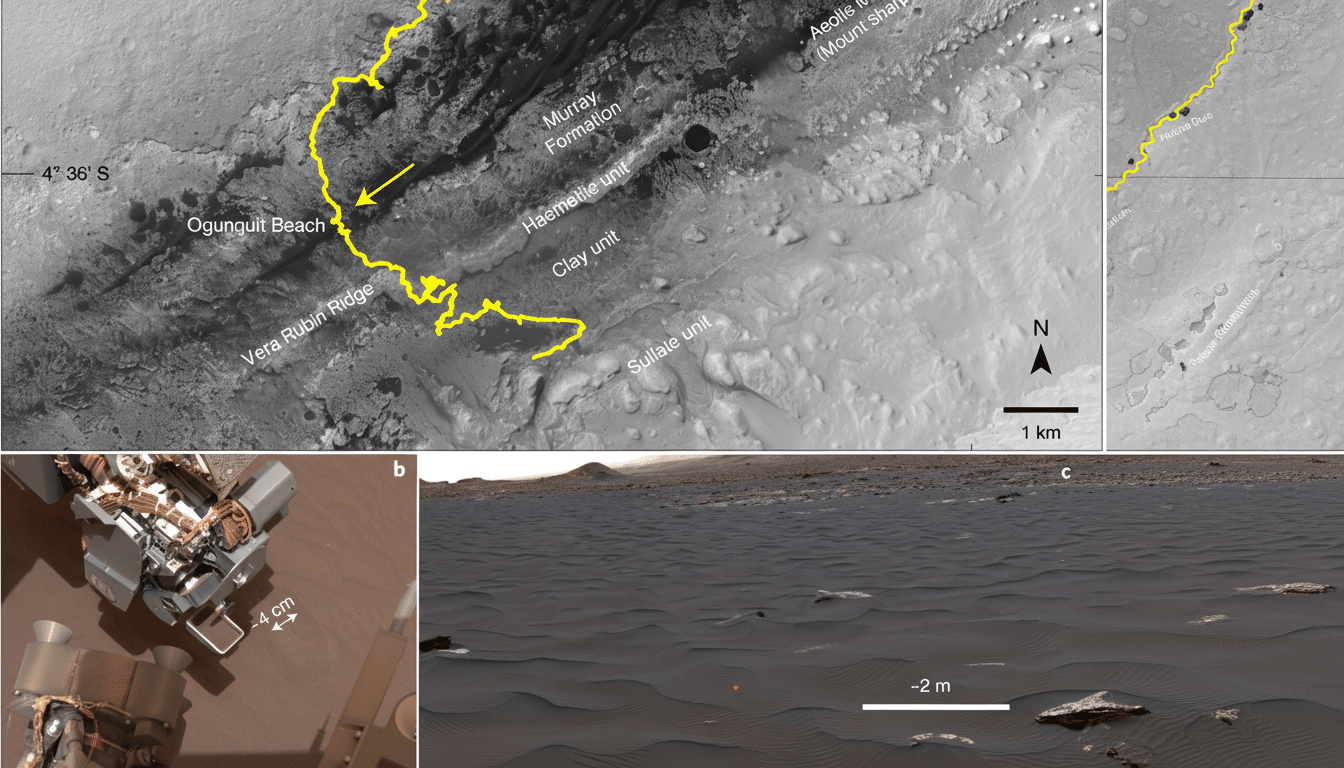

The new test focuses on fine-grained sedimentary rock at Nevado Sajama, a locale chosen after Curiosity identified clay minerals within a striking “boxwork” terrain—polygons of low ridges that crisscross the landscape. Clays are prime candidates for preserving organics because their layered structures can shield delicate molecules from radiation and oxidants.

To improve context for the drilling and sampling, the rover even illuminated the borehole at night using LED lights on its robotic arm, reducing shadowing that can obscure layering details. The geomorphology suggests the boxwork may have formed as the last trickles of groundwater flowed and then evaporated, leaving behind mineral-filled fractures. Such settings, on Earth, can trap and concentrate organic residues.

What Scientists Hope to Learn from Curiosity’s Test

Curiosity’s long-term objective is to decode habitability, not to deliver a definitive biosignature. Still, heightened sensitivity to organics matters: the detection of more complex or diverse compounds could reveal how ancient Martian environments processed carbon and whether those settings offered chemical pathways friendly to life. Any candidate molecules will be evaluated against multiple non-biological origins, including reactions involving volcanic gases, ultraviolet-altered dust, or instrument background.

Past findings frame the stakes. Curiosity’s SAM has previously detected organics in Gale Crater, while its companion rover, Perseverance, has identified intriguing materials in Jezero Crater that NASA officials say could be consistent with remains of ancient microbial activity, though alternative explanations remain plausible. Together, these missions are building a geochemical record that will guide how scientists interpret samples when they are eventually studied in Earth laboratories.

Key Numbers Behind This Milestone in Curiosity’s Mission

Since launch, Curiosity has logged roughly 352 million miles through space and another 22.5 miles across the Martian surface—an extraordinary run for a six-wheeled rover the size of a small car. Its onboard labs, SAM and CheMin, have analyzed dozens of drilled and scooped samples, turning Gale Crater into one of the most thoroughly studied extraterrestrial sedimentary basins.

This final TMAH deployment marks the culmination of years of instrument development, flight operations, and testbed iterations conducted by teams at JPL, Goddard, and partner institutions such as York University. It also validates Curiosity’s carefully rationed use of consumables, ensuring the solvent was reserved for a site with both clay protection and compelling geological context.

What Comes Next for Curiosity’s Search for Organics

Over the coming months, the science team will compare the Nevado Sajama results with the 2020 Mary Anning dataset to see whether the refined, three-step protocol exposes new compound classes or clearer structural signatures. Any robust detections will be weighed against instrument blanks and control runs to quantify confidence.

Even in the absence of a smoking gun, a richer organic inventory would sharpen our view of Mars’ ancient chemistry and help prioritize future targets within Gale’s stratigraphy. And while Curiosity does not cache samples, its findings provide crucial context for Perseverance’s astrobiology campaign and, ultimately, for the high-stakes laboratory analyses planned if Mars samples are returned to Earth.