The U.S. Court of Appeals shot down DJI's legal challenge to the U.S. Department of Defense, leaving the world’s best-known consumer-drone maker on the Pentagon’s list of Chinese military-linked companies and creating new doubt about its products in this country.

What the court decided in the DJI Pentagon case

The court said there was substantial evidence to support the Pentagon’s determination that DJI contributes to China’s defense industrial base. The judge would not endorse a separate allegation that the company is indirectly owned by the Chinese Communist Party, but noted the enhanced deference U.S. courts generally extend to national security findings made by defense officials.

Functionally, remaining on the Pentagon’s list under Section 1260H of the National Defense Authorization Act means DJI continues to be off-limits for procurement and certain federal programs. Though the listing is not a sanctions designation, it has often led to chilling of relations in the public and private sector among contractors sensitive about compliance risk, according to previous Reuters analyses and defense procurement experts.

It’s the latest U.S. restriction on DJI: The company was added to the U.S. Commerce Department’s entity list in 2020, limiting exports of U.S. technology to it, and has faced investment restrictions through Treasury’s Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies list.

Between them, those actions have reduced DJI’s ability to sell to government buyers and access some U.S. capital and components.

Why this matters for the U.S. drone market now

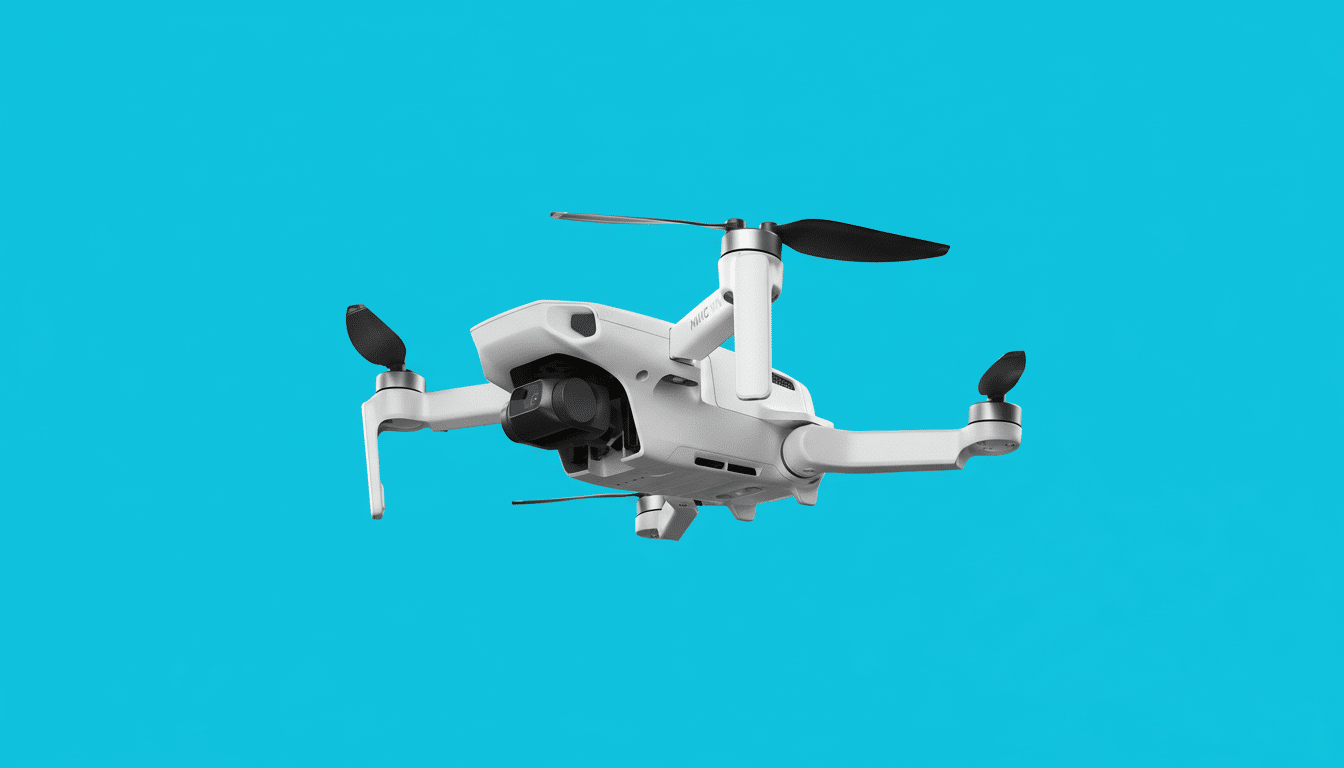

DJI has staked out the market for hobbyist and professional aerial imaging. Industry trackers like Drone Industry Insights and DroneAnalyst have calculated that the company has held a global share of the consumer and prosumer drone market in recent years at about 70 percent. And in public safety, much of the estimated 87 percent of U.S. police, fire and search-and-rescue programs that respond to incidents and map scenes use DJI platforms, according to surveys conducted by DRONERESPONDERS.

The federal and state restrictions already have pushed the agencies toward “Blue UAS” options that are vetted by the Defense Innovation Unit, from companies including Skydio, Teal Drones, Parrot and BRINC, among others. But those other options can be more expensive or weaker on features cherished by field operators, including camera ecosystems and flight-time benchmarks. In today’s decision, the probability that even cash-starved departments ratchet up vehicle diversification may rise exponentially — or else hold off on further purchasing until policy becomes clear or certain, which could impact thousands of units currently in refresh cycles.

There may also be ripple effects for retail channels. Consumer sales may still continue, but big distributors and enterprise integrators often fall in line with federal risk advice, which could throttle availability, financing, and after-sales support for DJI systems used in commercial inspection, construction, and agriculture.

Policy momentum toward a broader federal drone ban

The court loss comes amid increasing legislative and regulatory pressure. The legislation, the American Security Drone Act, tucked into a large defense bill that became law in December, bars most federal agencies from buying and operating foreign-made drones for national security reasons with only some waivers. Meanwhile, the Countering CCP Drones Act, which advanced in the House last year, aims to put DJI on the Federal Communications Commission’s list of covered entities — a move that might halt new device authorizations for them and could have a chilling effect on future sales in U.S. markets.

Several states have passed their own bans on Chinese-made drones for official use, creating a patchwork of regulations that complicates planning fleets of the devices. In conjunction with the Pentagon list, such steps indicate a policy direction that leans toward domestic and friendly suppliers, and could commit multi-year procurement roadmaps that do not include DJI.

DJI’s position and what’s next for users and buyers

DJI has repeatedly denied accusations that it feeds data to the Chinese government and maintains that it is privately owned. The company has pointed to a U.S. Data Security architecture — local data modes, offline operation and on-premises servers for enterprise clients — as proof that sensitive information can be kept in check. It can pursue further appeal, but the court’s deference to national security judgments suggests a very high bar.

Questions for end users in the near term are mostly practical: Can they continue to get their existing fleets serviced and insured, keep receiving firmware updates, and are there going to be deadlines from regulators for transition? We expect agencies reliant on federal funding to expedite the transition from White UAS to Blue platforms. Private companies and, potentially, hobbyists may get less of an immediate roadblock, but any steps taken by the FCC, or new state-level rules, could shift the situation in a hurry.

The larger message is that U.S. drone policy is coalescing around supply chain security and trusted origin, not just performance and price. With the Pentagon roster in place and momentum building on Capitol Hill, DJI’s U.S. presence faces its stiffest headwinds yet — even as domestic and allied manufacturers scramble to show that they can satisfy the market’s technical and cost demands at scale.