Commonwealth Fusion Systems has inked a power purchase agreement contract for over $1 billion with Eni, securing the future offtake of the startup’s first commercial fusion system demonstration plant from now until 2033. The deal, in the wake of an earlier agreement under which Google agreed to buy a significant fraction of ARC’s output, suggests that fusion is making the transition from scientific milestone to bankable energy product.

ARC will be a 400-megawatt facility outside Richmond, Virginia in the area near America’s largest cluster of data centers. Now that two marquee buyers are lined up as customers, CFS is positioning ARC as a seller of firm, carbon-free power for a grid groaning under digital demand and decarbonization imperatives.

Why this is a first-of-a-kind power contract for fusion

Terms weren’t disclosed, including the specific volume and duration. CFS executives say the structure is collaborative, but not punitive, recognizing the uncertainties that attend a first-of-a-kind plant. In practical terms, the contract provides lenders and investors a revenue spine for project finance — a must-have for any capital-intensive power asset, particularly fusion.

Power purchase agreements are the workhorse of clean energy deployment, but few exist yet for fusion. In setting a price and stipulating an offtaker, CFS is creating the bankability package equity and debt providers seek: a credible counterparty, contracted cash flow, and scale.

Why Eni is seeking expensive electrons from ARC

Eni, one of the world’s biggest energy companies and an investor in CFS, intends to put ARC’s electricity onto the grid rather than using it for itself. Early fusion power will almost certainly have a levelized cost premium, so selling it on just to make a profit is not going to be a profit center on day 1. The value proposition comes elsewhere: lending a hand in establishing a benchmark price for fusion, ensuring learning curve access and signaling to bankers (and governments) that blue-chip buyers will back procurement of offtake.

This playbook is well-worn territory from the early days of offshore wind and utility-scale solar, when pioneer off-takers took a higher price in the service of jump-starting supply chains. To Eni, the contract is a hedge on long-term decarbonization — and a way to help mold a market it anticipates will expand.

Focusing on the data center corridor near Richmond

ARC’s site selection close to Richmond is no accident. The world’s largest data center cluster is in Northern Virginia, and all of the interconnection queues across the mid-Atlantic are choked. According to the International Energy Agency, global data center electricity demand could roughly double by the middle of the decade, propelled in part by AI and cloud growth. That headwind is meeting corporate commitments to 24/7 carbon-free power — a commitment that companies like Google have committed to writing.

A 400-megawatt, round-the-clock source could join the club of firm clean energy resources that so many companies rely on today – alongside wind, solar, storage and demand management strategies. If ARC works as intended, it also offers the sort of high-capacity-factor output that grid planners hunger for and that data center operators are coming to need.

From SPARC to ARC: technical path and risks

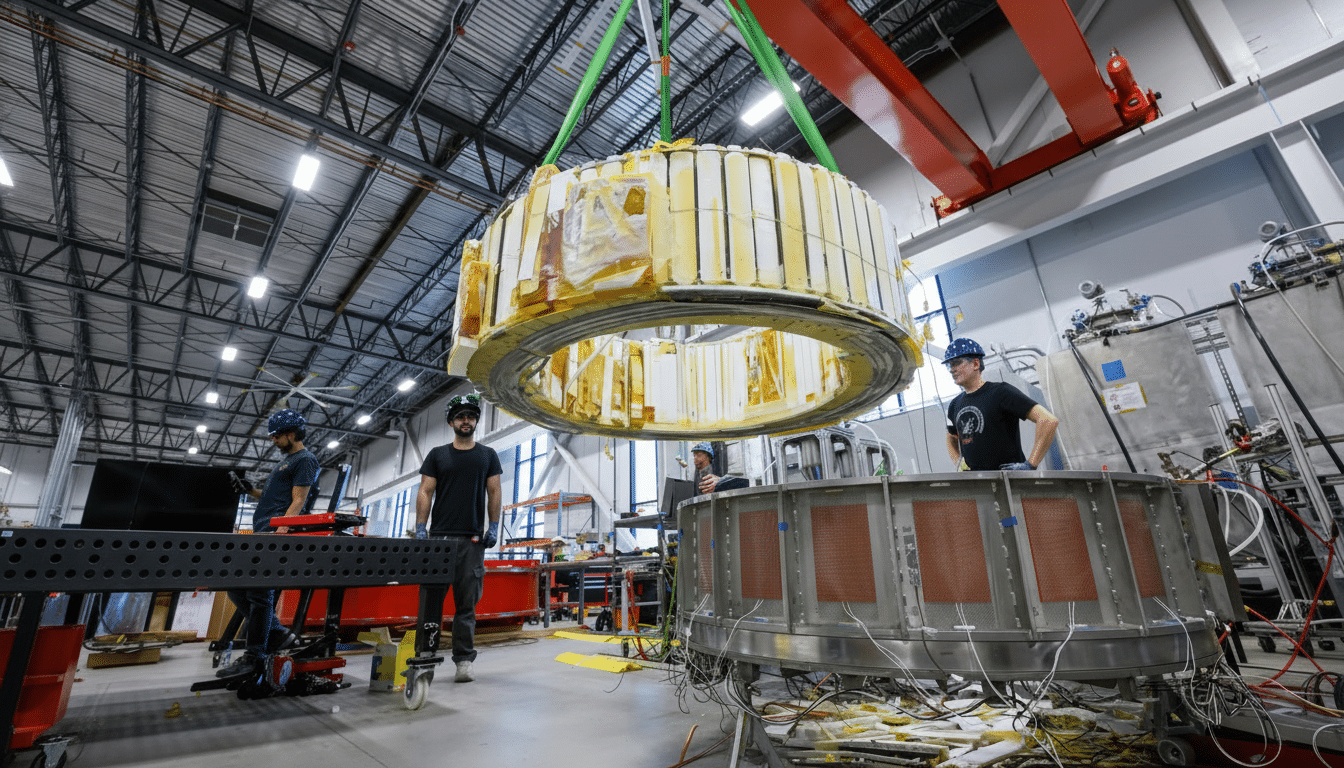

CFS’s near-term aim is SPARC, a demonstration-scale tokamak now being built in Devens, Massachusetts — the project CFS says is about two-thirds finished. SPARC is designed to demonstrate that high-field magnets made from high-temperature superconductors can confine plasma well enough in a compact device to achieve net energy gain—a claim backed by detailed simulations and earlier magnet tests reported with MIT researchers.

ARC scales that up to a grid-tied plant. The tokamak is designed to confine superheated plasma in a donut shape, with high-field superconducting D-shaped coils playing the role of the magnetic twist that forms within it, releasing energy through deuterium-tritium fusion. The promise is enticing, but critical engineering issues remain: plasma-wall interactions, heat exhaust, tritium fuel cycle management, maintainability and the rate at which components can be fabricated with power-plant reliability. CFS makes no bones about the fact that everything rides on what SPARC does.

Financing needs and policy tailwinds for fusion

CFS has raised almost $3 billion so far, including an $863 million round supported by investors like Nvidia, Google, Breakthrough Energy Ventures and Eni. That said, ARC can’t be financed entirely off of venture capital alone — long-term offtake agreements, potential government loan guarantees, and insurance solutions around performance risk will likely need to be in the capital stack.

Regulatory momentum helps. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has developed a custom licensing approach for fusion (as opposed to fission), minimizing friction while maintaining safety. State-level clean energy standards that take 24/7 carbon-free procurement into account, as well as federal incentives for manufacturing advanced energy products, further buttress the business case.

Considered together, the Eni deal, Google’s agreement to date and SPARC’s successful preliminary test run all amount to a changing guard: fusion electricity advancing from lab concept to commercial action.

The electrons are still a few years off, but the $1B+ PPA places an actual price signal on tech that has long been measured in promises. If the physics and engineering pan out, ARC’s customers will already be waiting.