Bone Temple doesn’t just continue the outbreak saga; it rips open the mythology of Jimmy Crystal, the self-anointed “sir” whose fanatic charisma reframes the franchise’s terror. Nia DaCosta’s film pivots the threat from the infected to a predator shaped by abandonment, pop-cultural detritus, and weaponized faith. The result is a chilling character study anchored by Jack O’Connell’s unnervingly playful menace and a screenplay that treats belief as both lifeline and blade.

A Villain Forged by Abandonment and Broken Faith

Bone Temple clarifies the moment Jimmy’s worldview calcifies: a church sanctuary dissolves into carnage; a father’s calling becomes surrender; a child’s safety net snaps. The necklace he clutches is less talisman than fracture point. Rather than excusing his later atrocities, the film shows how trauma and meaning-making collide to produce a leader who confuses pain with purpose.

This tracks with real-world findings on early adversity. Research on Adverse Childhood Experiences from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention links severe childhood trauma to elevated risks of aggression, substance misuse, and distorted coping. Bone Temple translates that data into dramaturgy: Jimmy processes loss not by grieving, but by inventing a cosmology that justifies control and cruelty.

When Culture Stops, Memory Becomes Doctrine

DaCosta’s most incisive choice is the notion that cultural time stopped in 2001. Jimmy’s references—the Teletubbies, toy fads, and a disgraced TV icon whose crimes were not yet public in his childhood—become canon in his private church. He doesn’t merely reminisce; he curates a theology from misremembered TV episodes and children’s merch, turning kitsch into catechism.

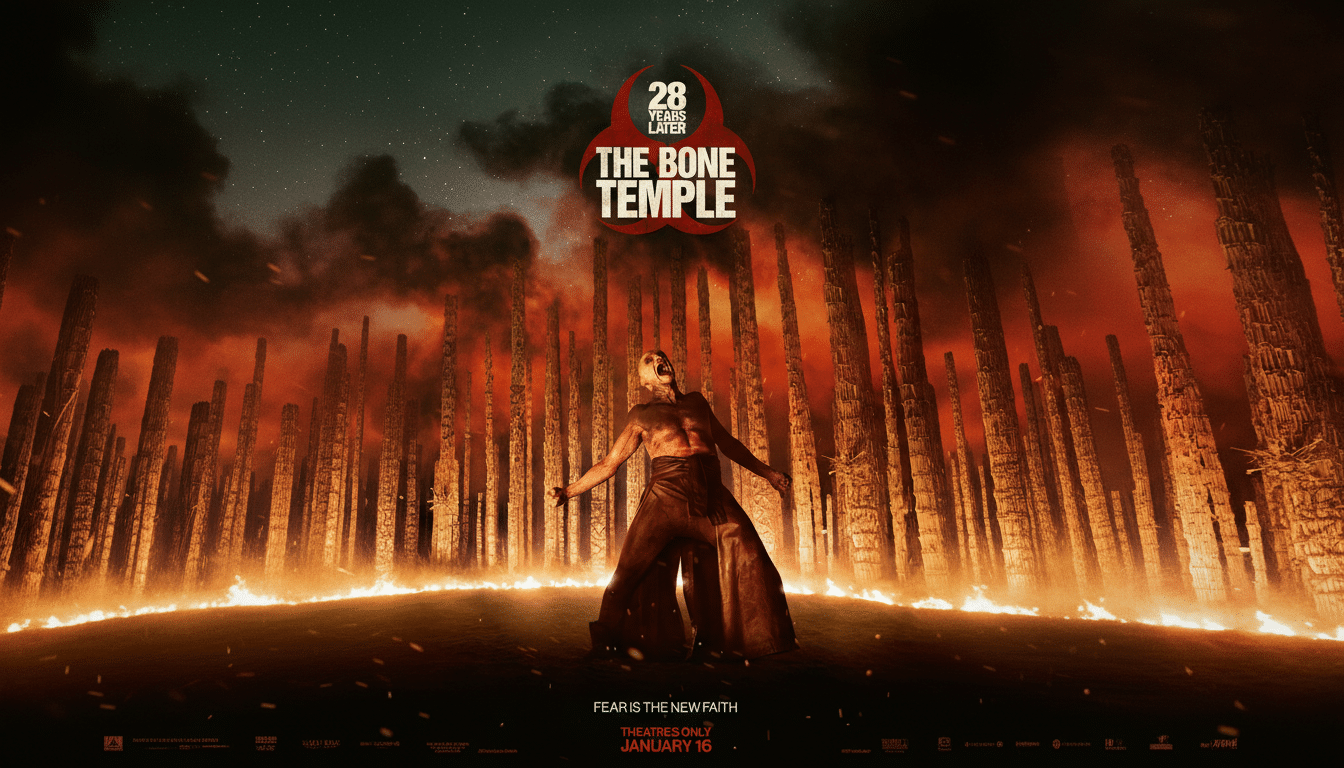

That cultural freeze explains the uncanny mirth in his sermons and the pageantry of his gang, the Fingers, who mimic his look and liturgy. Sociologists often note that collapsed information ecosystems empower charismatic figures to fill the vacuum with invented truths. Bone Temple visualizes that vacuum: jelly sandals and dead Tamagotchis repurposed as relics, a nursery-rhyme cadence carrying threats, and a leader mistaking nostalgia for revelation.

Ritualized Violence as Social Glue in Jimmy’s Cult

Jimmy’s “charity”—his word for torture—exposes how he converts violence into belonging. Farmhouse raids unfold like liturgies, with repeated phrases, shared gestures, and theatrical cruelty that binds followers through complicity. The horror lands not in jump scares but in the deadened normalcy with which the Fingers participate.

Criminology literature has long observed how groups manufacture cohesion via rites that erode empathy and reward obedience. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has documented similar dynamics in armed groups that use ritualized brutality to enforce loyalty. Bone Temple maps that logic onto Jimmy’s micro-theocracy, where pain is pedagogy and spectacle is control.

The Scientific Counterweight to Jimmy Crystal’s Faith

Enter Dr. Ian Kelson, the rationalist counterpart who studies the infected as treatable, not damned. Their collision reframes the franchise’s central question: is the apocalypse a medical crisis or a spiritual void? By allowing Kelson’s inquiry to coexist with Jimmy’s sermonizing, the film sidesteps caricature. It treats the infected as ill and Jimmy as a person who became monstrous—distinctions the World Health Organization has urged in public health narratives to reduce stigma and expand empathy.

Crucially, Kelson doesn’t just debate; he diagnoses. His cautious probing teases out Jimmy’s lonely cosmology, where a child’s last glimpse of his father mutates into a Satanic origin myth. That interrogation strips away the bravado and exposes an ache Jimmy can’t admit without losing his dominion. The scene plays like a forensic audit of belief, and it rattles.

Performance Choices That Humanize the Monster

O’Connell threads a wicked needle: he’s funny without inviting affection, magnetic without glamour. The giggles, the TV catchphrases, the sing-song menace—they’re coping mechanisms upgraded into weapons. DaCosta’s camera often holds steady through his rituals, denying viewers the relief of a cut. That restraint underscores her thesis: if you watch Jimmy long enough, you see the person and the performance, the wound and the knife.

The Fingers mirror this duality. Their synchronized movements and borrowed aesthetics read like a youth culture born from scraps. In that sense, they’re less henchmen than a case study in how adolescents in collapsed systems mirror power to survive—an echo of what child protection NGOs have recorded in conflict zones where identity is assembled from whatever signals still circulate.

What Bone Temple Ultimately Reveals About Power and Belief

The film’s boldest statement is that apocalypse doesn’t create evil so much as expose the stories people tell to live with it. Jimmy’s gospel is a grief script that calcified into tyranny. His totems aren’t random; they’re the last familiar objects from a childhood that ended mid-sentence, repurposed into a belief system that validates his power and numbs his pain.

By the time the credits roll, Jimmy Crystal stands not as a stock villain but as the franchise’s most unsettling mirror: a man who found certainty in noise, family in fear, and holiness in harm. Bone Temple makes clear that defeating him won’t be a matter of firepower alone. It will require dismantling the myth that gave him a crown—and confronting the loneliness that keeps it glued to his head.