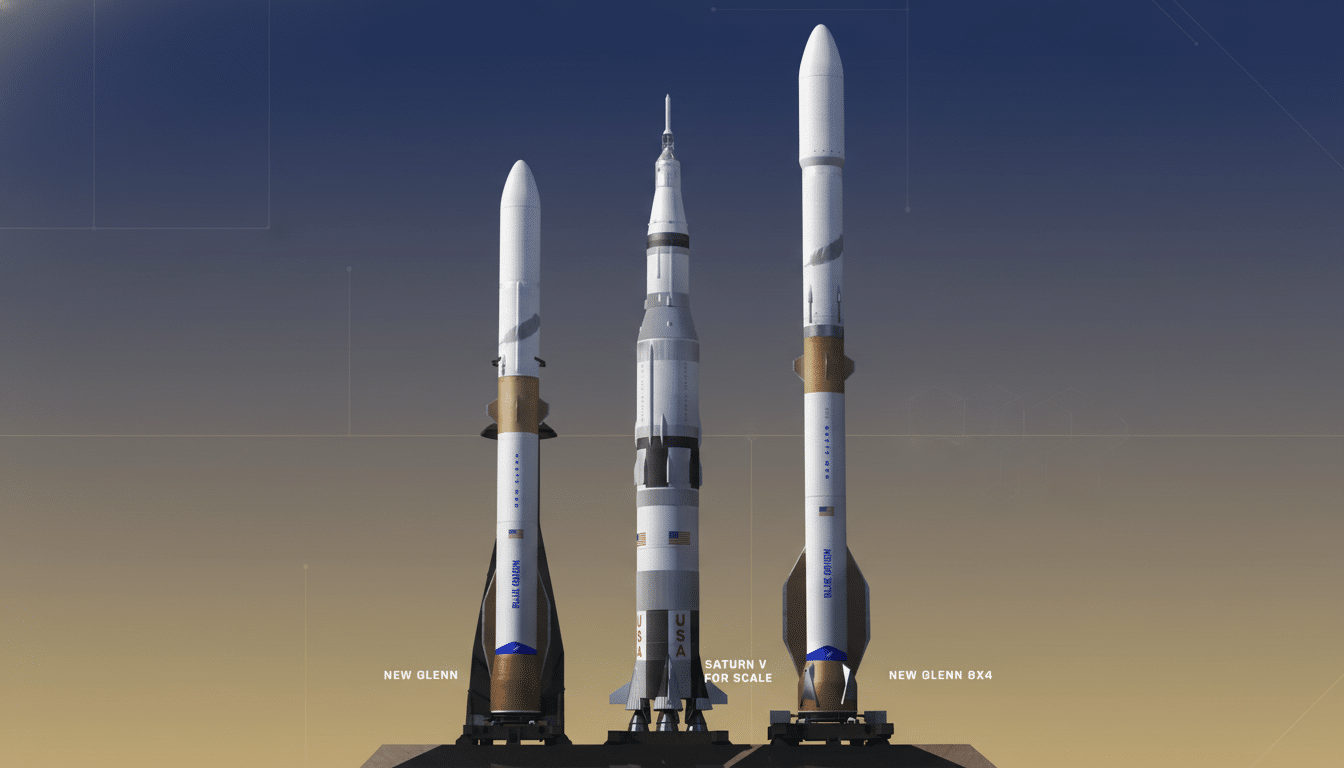

Blue Origin is developing its New Glenn launch system, which now has a super-heavy version that would be taller than NASA’s monster-sized Saturn V rocket, iconic of the Apollo era. The new configuration moves the rocket into the top rank of heavy-lift vehicles and puts the company firmly in contention to haul outsized payloads to low Earth orbit and beyond.

The company’s announcement comes shortly after a successful second New Glenn mission, underlining that Blue Origin plans to scale capability and cadence at the same time. (The reworked family will be available in two different versions, which the company has adopted as naming conventions of sorts: New Glenn 9×4 and New Glenn 7×2.)

A Bigger New Glenn in the Super-Heavy Class

The super-heavy New Glenn 9×4 will put nine engines on its reusable first stage and four on the upper stage, compared to the seven and two that make up today’s baseline vehicle. With the extra propulsion and stretched architecture Blue Origin says will boost payload capacity to “over 70 metric tons to low Earth orbit,” that’s enough of a jump for missions that used to demand either multi-launch construction or an entirely different rocket.

Blue Origin also stressed a larger payload fairing, the shroud that protects satellites as they are hurled into space. A larger fairing is as important as raw thrust: It dictates what can physically fit atop the rocket, from bus-sized Earth-observation platforms to heavy lunar cargo modules. The company is obviously hoping to compete on missions for things like mega-constellations, deep-space probes, and military assets.

Crucially, the 7×2 version is not going anywhere. “We’re getting more thrust out of that configuration next, and we are bringing reusability to not just the engines but also the fairings, with other changes for quicker turnaround times to higher flight rates at a lower cost per mission,” said Blue Origin.

How It Compares With Saturn V and Starship

Blue Origin says the updated version of New Glenn will stand taller than Saturn V. Saturn V clocks in at around 110.6 meters high, according to NASA’s historical records, and the Starship stack is about 121 meters. That would put the new New Glenn in company with only one rocket that is flying today, nearing the size of that vehicle.

When it comes to performance, the picture is mixed. Per SpaceX, Starship in its current form has a theoretical payload of around 100 metric tons to low Earth orbit (several iterative improvements are already in the works). Blue Origin’s “over 70 metric tons” goal for New Glenn plants it between Starship and NASA’s Space Launch System Block 1, which is rated by NASA at around 95 metric tons to LEO. The United Launch Alliance Vulcan falls far short of that class, advertising less than 30 metric tons to LEO.

Thrust figures provide additional context. Blue Origin’s BE-4 engines provide about 2.4 MN thrust at sea level, so a booster with up to nine of them would offer something like 21–22 MN at liftoff. That’s a lower first-stage total than Saturn V (~34 MN) and far below Starship’s Super Heavy (~70+ MN), but considering modern vehicle structures, staged reusability, and high-efficiency upper-stage operations, mission capability isn’t just about raw takeoff thrust.

Why the Bigger Payload Fairing Matters for Missions

Fairing volume, not mass limits, is increasingly what satellite builders design around. A bigger fairing allows multiple large satellites, heavier sensor suites, and integrated space tugs to be deployed in a single launch. In addition, it simplifies integration as there is no need to fold or hinge, or to section rigid, fragile payloads to accommodate smaller envelopes.

The market signals are clear. Commercial constellation operators are packing more satellites onto a single launch in an effort to drive down the per-satellite cost, and government customers continue fielding bulkier and power-hungrier spacecraft. A high-volume fairing, combined with a super-heavy lift class, exactly meets those burgeoning needs.

Updates on Reusability and Launch Cadence

By reusing fairings on the 7×2 configuration, Blue Origin is taking a page from the playbook that has helped other launch service providers save millions per mission. Combined with discrete thrust increases and ground-processing efficiencies, the changes are designed to shorten turnaround times and help establish a flight cadence necessary to meet the needs of customer constellations and the government.

Reusing the first stage is still a central part of New Glenn. The company is gradually industrializing BE-4 engine production and booster-refurbishment flows, a qualifying condition for driving unit prices down and ensuring the super-heavy 9×4 variant has enough flight frequency to make business sense.

Relevance for Lunar and Security Missions

Blue Origin already has a NASA contract to develop a human landing system for upcoming Artemis missions, and the company has also been busy building its Blue Moon family of cargo landers. The larger, heavier-lift New Glenn would “require less aggregation” of that existing lunar hardware into the desired manifest for such campaigns by taking it to the Moon while strung out across fewer pieces and with more margin.

On the defense side, extra lift and volume in the fairing mesh with priorities identified by the U.S. Space Force and intelligence community, such as the rapid placement of resilient constellations and heavier national security payloads.

Blue Origin even winked at “Golden Dome” requirements in its materials, a code for massive missile warning and defense architectures that require large apertures and big buses.

If Blue Origin builds both versions simultaneously, flying the upgraded 7×2 as much as possible and saving the heavier lifter for only the heaviest missions, it will offer satellite operators and government customers a menu that includes medium, heavy, and super-heavy lift. That move could remake the competitive dynamics of a market that has long been dominated by a few vehicles at each end of the capacity spectrum.

There’s not much doubt about Blue Origin’s intent in a render shared earlier: a super-tall and thin New Glenn squeezes the pad as a large Moon watches. As much as the message is about vehicle, it’s also about destination: Build a rocket that can lift more, fit more, and fly often, and new mission architectures are suddenly possible.