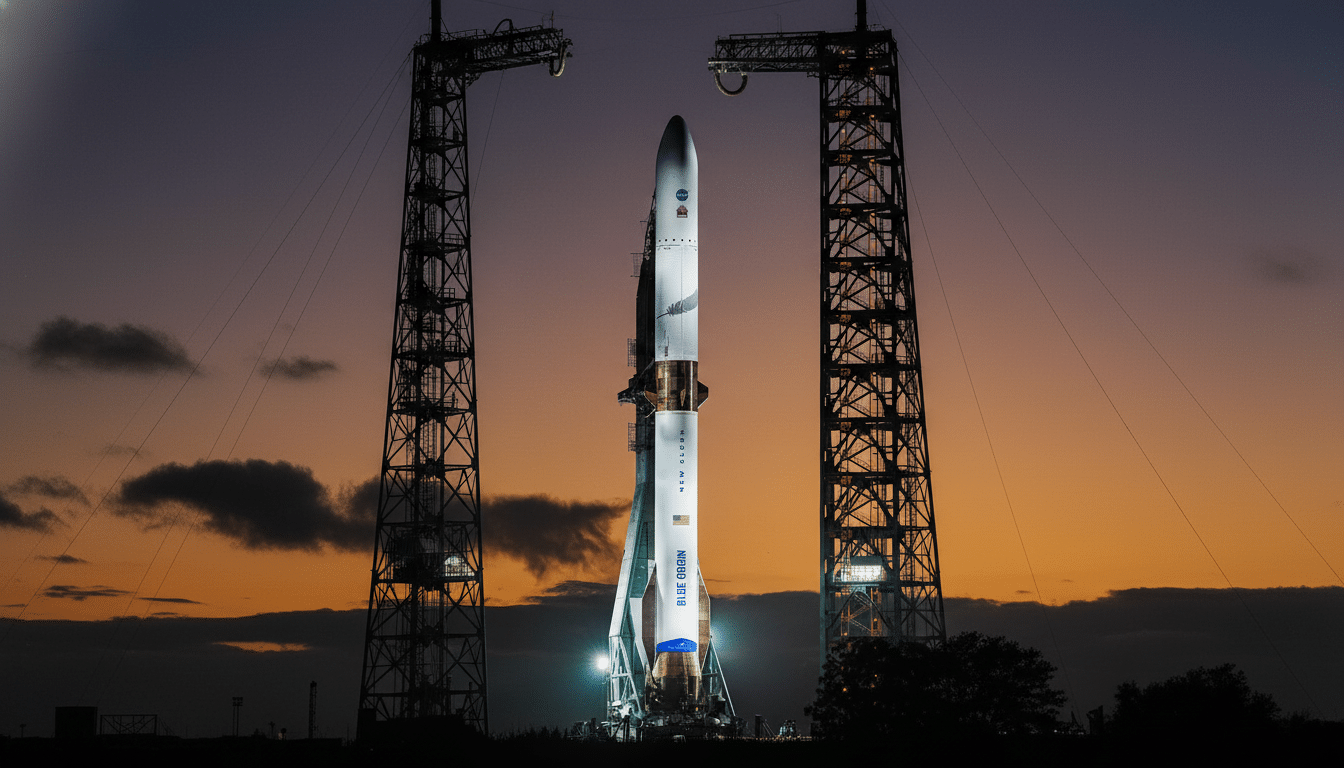

Blue Origin has paused its second launch attempt for New Glenn due to “increased solar activity, which poses an increased risk” to NASA’s ESCAPADE mission aboard the rocket.

The call was made just hours before liftoff from Cape Canaveral, highlighting how space weather can disrupt even what would otherwise be perfectly timed campaigns when the payload is a deep-space one.

The company said the pause comes from worries about the potential impact of continuing solar storms on spacecraft systems. New Glenn made a successful debut earlier this year as a (mostly) demonstration mission; this flight is the first with a commercial payload, and the team is being cautious while solar conditions settle down.

Solar weather complicates missions to deep space

Solar eruptions can flood near-Earth space with energetic particles or disturb Earth’s magnetic field and, in doing so, form radiation and communications environments that are anything but routine. Forecasters at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center issued alerts about high geomagnetic and solar radiation storm conditions that can cause GPS coverage to be lost, radios to go long quiet, and star trackers to “saturate”—all of which could pose serious safety risks for many initial spacecraft operations.

For strong events, >10 MeV proton fluxes can exceed normal launch commit criteria, and 200–400 km upper-atmosphere densities balloon by double-digit percentage numbers. A dramatic example: a geomagnetic storm early in 2022 added drag, which was enough to prematurely render dozens of new Starlink satellites too unstable to avoid falling back into the atmosphere. For deep-space probes that need to perform accurate burns and touchy checkout sequences soon after separation, the risk calculus skews heavily toward waiting.

ESCAPADE—two small spacecraft to be outfitted with instruments for studying the Martian magnetosphere and its interactions with the solar wind—will have to get through that early post-launch period on clean telemetry and on trustworthy navigation. Increased radiation can cause single-event upsets in avionics and blind optical sensors, while disturbed ionospheric conditions can disrupt communications. Standing down until the storm of solar particles abates is textbook risk management.

Why New Glenn is taking it slow during solar storms

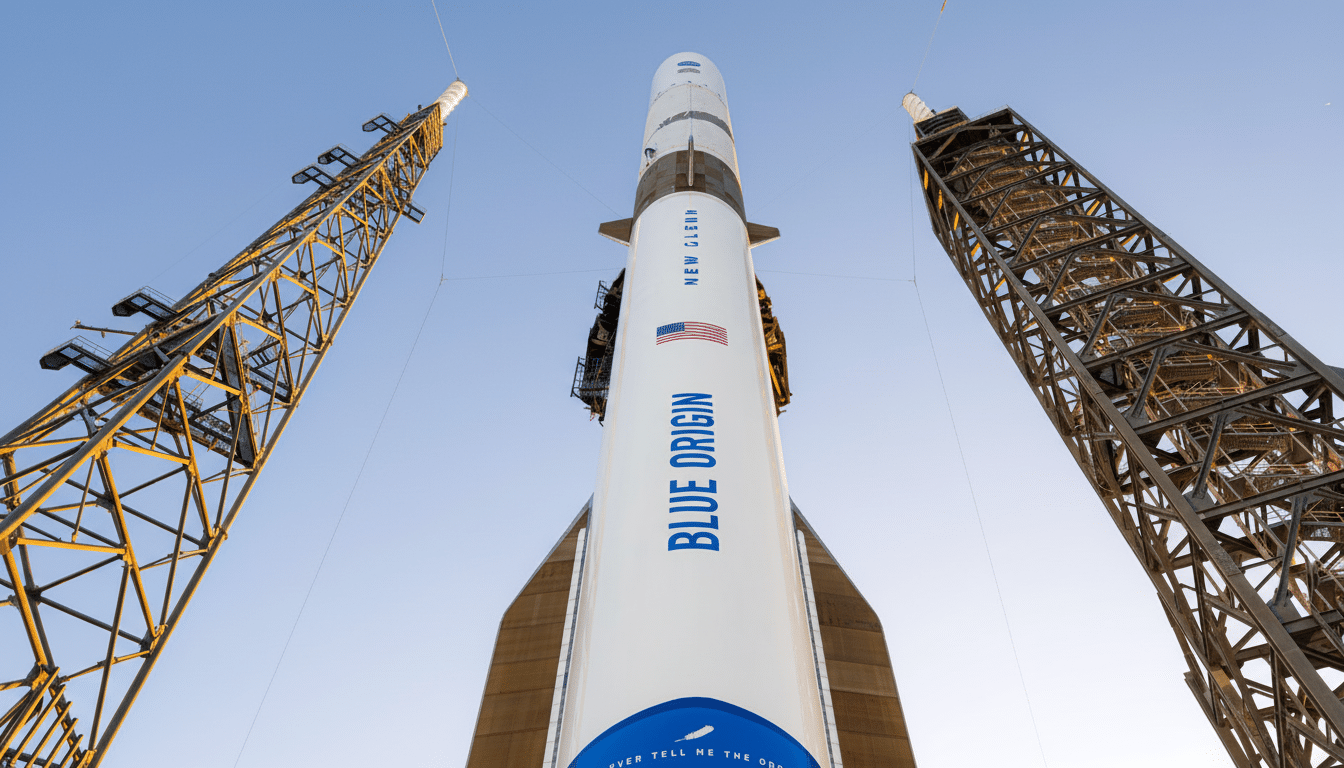

New Glenn is a heavy-lift vehicle, and Blue Origin is billing this second flight as an increase in complexity. The first flight was a proof of life for major systems; it will now have to carry and protect an operational payload on a deep-space journey. That makes the solar storm a non-negotiable friction rather than an inconvenience.

This latest scrub is the result of a series of challenges typical to an active launch range: previous attempts were delayed by bad weather, a cruise ship intruding into the range, and ground systems issues. None of those are out of the ordinary—Space Launch Delta 45, which controls Eastern Range operations, routinely activates tight safety corridors and weather rules just like this when it comes to heavy-lift missions in order to address the higher stakes.

Engineers also take into account the “first-light” realities of a new booster. And even when hardware is functionally sound, operators usually construct conservative guardrails around environmental conditions. For a spacecraft en route to Mars, that means tighter radiation envelopes and tighter envelopes on navigation quality and comms stability in those first few orbits and any injection burn or hops.

Range criteria and spacecraft risk conditions

That article noted that launch teams have well-established launch commit criteria that go beyond winds and lightning. NASA and the U.S. Space Force rely on thresholds for certain components of space weather (e.g., proton flux limits, typically monitored at >10 MeV; Kp geomagnetic indices) in go/no-go decisions. When those measures spike, risk to avionics, guidance sensors, and communications links soars right along with them.

SEP events may result in single-event upsets in flight computers, noise in inertial measurement units, and loss of lock in star trackers. Of lesser concern are degradations to GPS accuracy and to S-band tracking and command caused by disrupted ionospheric conditions both on the ground and in flight. For a twin-satellite science mission that requires crisp early commissioning, the safe play is to hold off until conditions are calmer.

What the delay means for the launch manifest

Operationally, a solar-weather scrub was an inconvenience that delivered benefits in the long term. There’s more at stake than squeezing into an iffy window: protecting ESCAPADE’s early operations and New Glenn’s strong reliability record. Mars windows last several days, extending to broader interplanetary windows, and teams can recycle countdowns once NOAA outlooks suggest particle flux and geomagnetic conditions are trending back toward nominal.

The broader competitive context is obvious: all major launch providers have delayed for space weather—from ULA to SpaceX—when the radiation and comms environment would move against an acceptable risk posture. Blue Origin’s move is consistent with industry practice and indicates a maturing posture for New Glenn as the vehicle prepares for an increasingly filled manifest of government and commercial missions.

In an age when digital auroras tend to win the day on social-media feeds, however, the invisible side of solar storms still sets legitimate constraints and schedules on spaceflight. For New Glenn and ESCAPADE, however, the smarter move is also the simplest: just wait for the Sun to settle down a bit, then go.