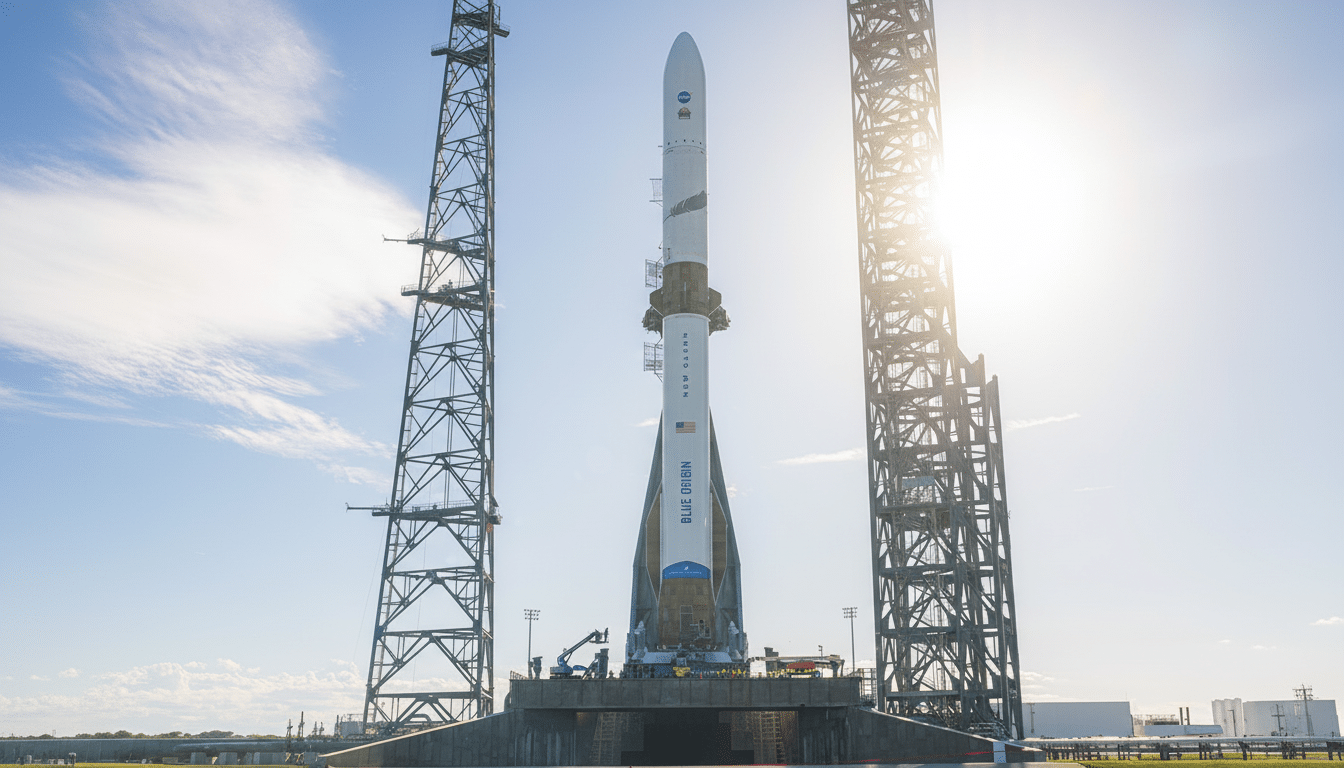

Blue Origin achieved a critical first by directing its New Glenn first stage to land on a barge at sea, demonstrating the reusable potential of the heavy-lift rocket and putting it in an exclusive club of orbital-class vehicles that can fly back and land as they were launched.

How the landing unfolded, from reentry to touchdown

The seven-engine BE-4 first stage, known as “Never Tell Me the Odds,” separated cleanly and executed a precise reentry burn before homing in on Blue Origin’s downrange vessel Jacklyn.

- How the landing unfolded, from reentry to touchdown

- A Mars assist on the same flight: NASA’s ESCAPADE

- Why this landing matters for reuse and launch markets

- Capabilities and customers in the offing for New Glenn

- Lunar stakes for Blue Origin and its Blue Moon plans

- What to watch next as Blue Origin targets reusability

Footage from the company’s webcast showed the booster maneuvering horizontally over the deck before coming to rest on six landing legs some 375 miles offshore. That side-to-side “hover-slide” is an indicator of mature guidance and control, and for a vehicle the size of New Glenn, it’s even more striking.

The ascent was powered by BE-4 engines fueled by liquefied natural gas (methane) and liquid oxygen, a combination that provides benefits such as clean combustion and reusable engines. The rocket’s twin BE-3U hydrogen engines on the second stage boosted the payload into orbit once the flight of stage one began.

A Mars assist on the same flight: NASA’s ESCAPADE

Piggybacked atop New Glenn were two miniature probes for NASA’s ESCAPADE mission, which will begin the first-ever study of the Martian magnetosphere. Produced by Rocket Lab, they were sent on an interplanetary trajectory after a second-stage burn. NASA bought this launch for about $20 million, suggesting the agency will pay more to fly new vehicles when the science risk profile permits. That’s a goal of significant vagueness when it comes to deep space payloads, and is another strong indicator of how having additional heavy-lift capability can create room around price targets for specific missions.

Why this landing matters for reuse and launch markets

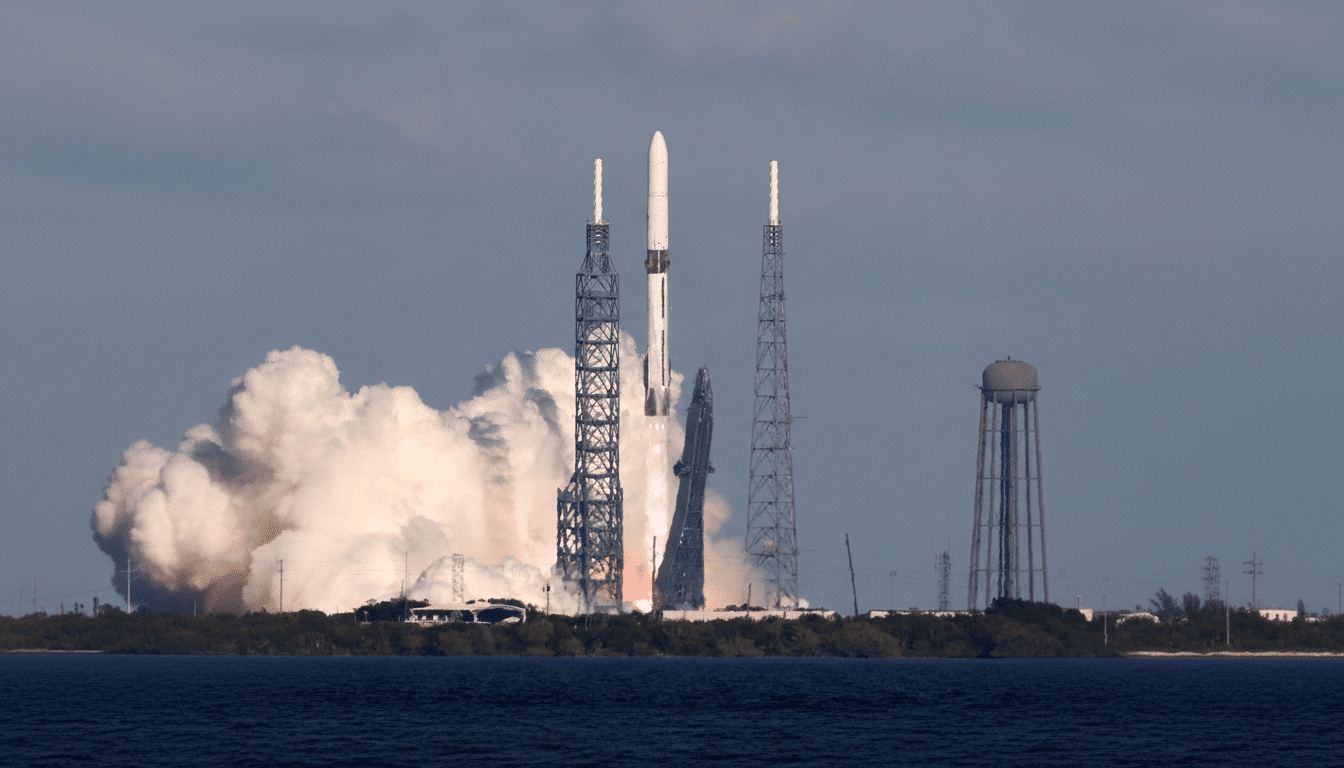

The recovery makes New Glenn one of only three orbital-class rockets with that capability, along with SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy. SpaceX has proved, with hundreds of booster landings and rapid-turnaround reflights, that reuse has an economic payoff. Blue Origin’s entrance into that regime is an indication of increasing competition — and capacity — in a launch market that is bloating with broadband constellations, lunar logistics, and science payloads.

Technically speaking, the milestone proves that the BE-4 can perform in a challenging recovery profile. It is the same engine that drives United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan, and every other successful BE-4 flight adds confidence across those various programs. Blue Origin has said the design has been developed for multiple missions, aiming for dozens of flights over its life that — if achieved — could lower costs in terms of dollars per kilogram and provide more schedule assurance to customers.

Capabilities and customers in the offing for New Glenn

New Glenn is designed to be big: Blue Origin lists a carrying capacity of nearly 50 tons to low Earth orbit and approximately 14 tons to geostationary orbit. That paves the way for heavier satellites, multi-satellite rideshares, and high-energy missions that previously needed two missions or umbilical strategies to refuel an upper stage.

There’s already significant demand on the books. As part of Project Kuiper, Amazon has already booked at least a dozen missions on New Glenn as well, for a multi-provider approach to deploying its broadband constellation. AST SpaceMobile is developing the oversized BlueBird satellites to connect directly to smartphones, and it views New Glenn’s large fairing volume and lift as ideal for its plans. These commitments were a high-flying practical statement of confidence that winged in tandem with the booster’s first landing.

Lunar stakes for Blue Origin and its Blue Moon plans

But beyond commercial satellites, New Glenn’s return sets crucial momentum into Blue Origin’s dreams of the moon. The rocket is set to send the Blue Moon Mark 1 cargo lander — a forerunner to surface shipments — into space. Further down the road, the company is working on the crew-capable Blue Moon Mark 2 in response to a multibillion-dollar NASA award for Artemis. It’s not just a cost story when you can reuse the boosters, it’s a cadence story. If there is to be the sustained lunar logistics that this will require, it will need not just frequent launches but predictable ones, and reusability is what delivers a space launch tempo that can fit with other systems.

What to watch next as Blue Origin targets reusability

The immediate test will be turnaround speed: how quickly Blue Origin can inspect, refurbish, and refly this recovered stage. SpaceX’s experience demonstrates that taking days or weeks instead of months and years off from one flight to the next is a game-changer, and Blue Origin will seek similar gains as it wends its way through first-flight learning curves. That also includes fairing recovery, and second-stage performance improvements to optimize payload envelopes.

As the company continues to link multiple recoveries, certify higher reuse counts, and keep its manifest moving — batches of Kuiper birds, oversized commercial satellites, and lunar hardware — New Glenn will go from milestone machine to reliable workhorse.

That change would effectively double the industry’s launch capacity and provide true redundancy to heavy-lift access to space.

For the time being, the headline speaks for itself: a big booster rises, back on its feet at sea again, and a new contender proves that precision landing at orbital scale is anyone’s game these days.