Avalanche is betting that the fastest path to practical fusion isn’t a cathedral of steel and superconductors but a device that fits on a workbench. The startup has secured $29 million in new funding to accelerate development of compact reactors it says can be built, tested, and improved at a cadence that big-budget megaprojects can’t match.

A Compact Path To Fusion Using Electrostatic Orbits

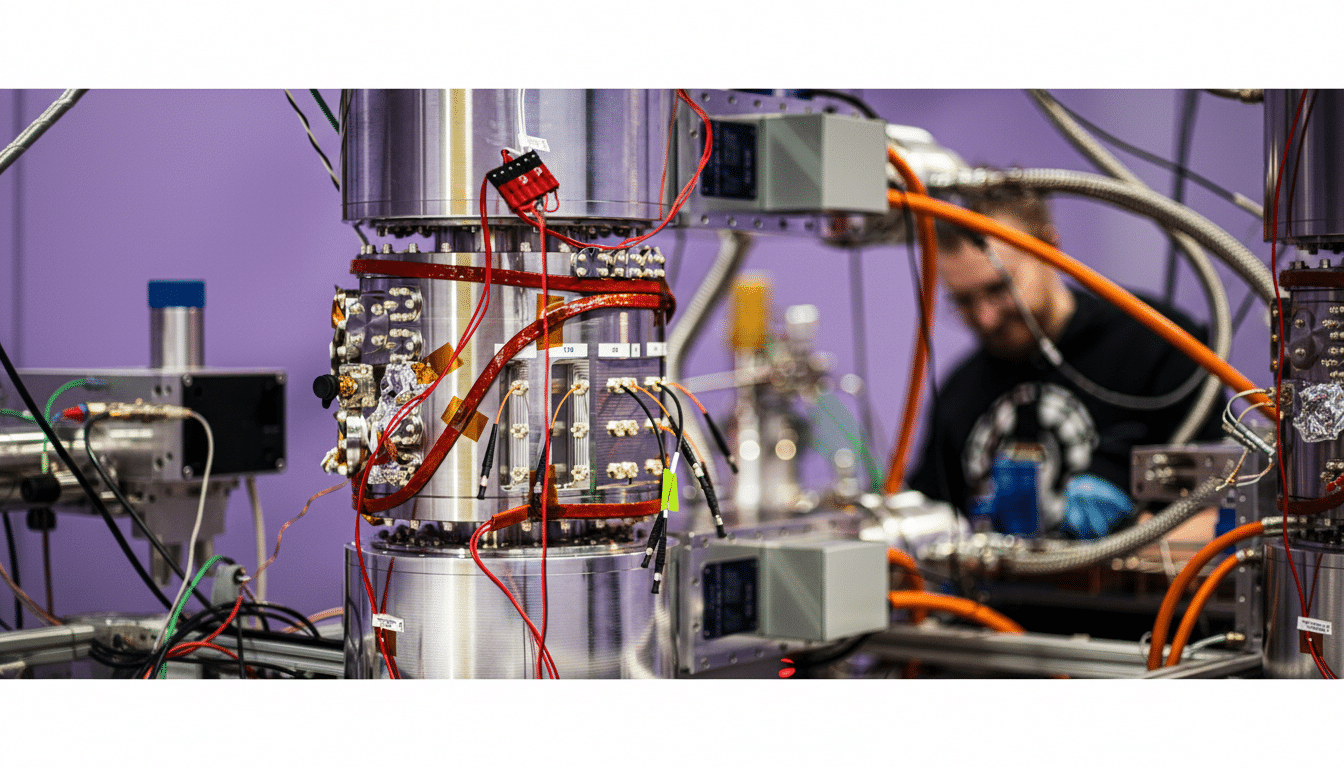

Instead of relying on colossal magnets or vast arrays of lasers, Avalanche uses extremely high voltages to draw plasma into stable orbits around an electrode, with modest magnetic fields added for order. As ions tighten their orbits and pick up speed, collisions rise and fusion reactions follow. The company’s current device measures just nine centimeters across—an unusual scale in a field known for multistory equipment.

The pitch is straightforward: smaller machines enable faster iteration. According to the company, engineers have been able to introduce design changes and run new shots as often as twice a week, learning with each cycle. That tempo is impractical when a single component swap on a stadium-sized tokamak can take months and millions.

Engineering By Iteration Not Megaprojects

Avalanche’s approach borrows from modern aerospace playbooks. Leadership with experience at Blue Origin says the lesson is to shrink hardware, multiply experiments, and treat hardware as a rapidly evolving product rather than a one-off demonstration. In fusion, where unforgiving physics and exotic materials make every improvement hard-won, compressing learning cycles is a competitive weapon.

The company plans to scale its reactor to 25 centimeters in diameter, targeting roughly 1 megawatt of fusion power on-device. The goal is longer confinement, higher collision rates, and a credible shot at Q>1—the moment a system outputs more power from fusion than it consumes to run the reaction. In fusion parlance, Q is the ratio of power out to power in; clearing 1 is the symbolic and technical breakeven that separates intriguing experiments from energy machines.

Chasing Q>1 With Smaller Magnets and Electrostatic Fields

Avalanche’s electrostatic method differs from high-field tokamaks being pursued by Commonwealth Fusion Systems, which rides advances in high-temperature superconducting magnets, and from pulsed magneto-inertial approaches such as Helion’s field-reversed configuration. Those companies have raised sums ranging from hundreds of millions to several billions; Avalanche’s total to date sits at about $80 million, including backing from R.A. Capital Management, 8090 Ventures, Congruent Ventures, Founders Fund, Lowercarbon Capital, Overlay Capital, and Toyota Ventures.

Operating at small scale doesn’t eliminate fusion’s classic hurdles. Electrostatic systems must deal with heat loads, electrode erosion, and bremsstrahlung radiation that can sap energy. Avalanche argues that careful shaping of fields and electron control with auxiliary magnets can mitigate losses, while rapid hardware cycles accelerate the search for robust materials and geometries.

Building A Fusion Testbed And Supply Chain

To speed progress and de-risk operations, Avalanche’s FusionWERX facility serves as both a home base and a neutral proving ground. The company says it is building capability to handle tritium—the hydrogen isotope central to most near-term fusion fuel cycles—so teams can test integrated systems under realistic conditions. Notably, Avalanche rents time to outside groups, a practical way to monetize infrastructure while fostering an ecosystem.

Tritium licensing and supply are nontrivial. Global inventories are tight, historically sourced from heavy-water fission reactors. Any firm planning grid-scale fusion must navigate fuel availability, handling, and breeding. By moving early on licensing and facility readiness, Avalanche aims to reduce one of the sector’s silent bottlenecks.

Why Thinking Smaller Could Scale Faster for Fusion

There’s a strategic angle to compact fusion that goes beyond R&D speed. Small, modular reactors are easier to manufacture in series, learn down the cost curve, and deploy near loads that need heat as much as electricity—industrial sites, chemical processors, and data centers. In heavy industry, even a few megawatts of reliable high-temperature heat can displace fossil boilers and cut emissions quickly.

The broader field is inching forward. The National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has demonstrated net energy gain in single-shot experiments, proving the physics but not the power plant. ITER’s international tokamak effort targets sustained burning plasmas at vast scale. Avalanche is carving a third path: make the machine small enough to prototype relentlessly, then scale replication, not size.

The Stakes and the Timeline for Compact Fusion

Investors are placing diversified bets across fusion modalities because the upside is enormous and the technical risks differ. Avalanche’s raise is modest by sector standards, but the company frames that as a feature: more shots on goal per dollar. If the 25-centimeter system lifts confinement and boosts reaction rates as planned, the firm believes it can close the gap to Q>1 on a timeline comparable to better-funded peers.

No one can promise when fusion crosses from demonstrations to dependable power. What’s clear is that the industry is splitting into two philosophies—go big to capture peak performance per machine, or go small to learn faster per month. Avalanche is making the smaller bet, and in fusion, speed of learning may be the most valuable energy source of all.