AST SpaceMobile is a direct shot across the bow, in fact, of the way SpaceX plans to run its satellite-to-phone service, an approach that it argues could gum up low Earth orbit. The Texas-based company says it can achieve global mobile coverage with an order of magnitude fewer spacecraft, and positioning “fewer, more capable” satellites as a cleaner path to connectivity.

In a public document laying out its plans for responsible space operations, AST extolled itself for employing debris mitigation and controlling for brightness, and boasted that approximately 90 high-power satellites would cover the planet—instead of the thousands offered by competitive constellations.

The criticism comes squarely at Starlink, which already consists of several thousand satellites and has filings that would boost that total to about 30,000. SpaceX, for its part, has suggested that AST’s large “tennis-court-sized” vessel might create complications for orbital safety. The two are now headed toward a regulatory train wreck as the F.C.C. considers AST’s application to put a network of as many as 248 satellites over the United States to serve as a direct-to-cell network.

Why AST thinks less is more

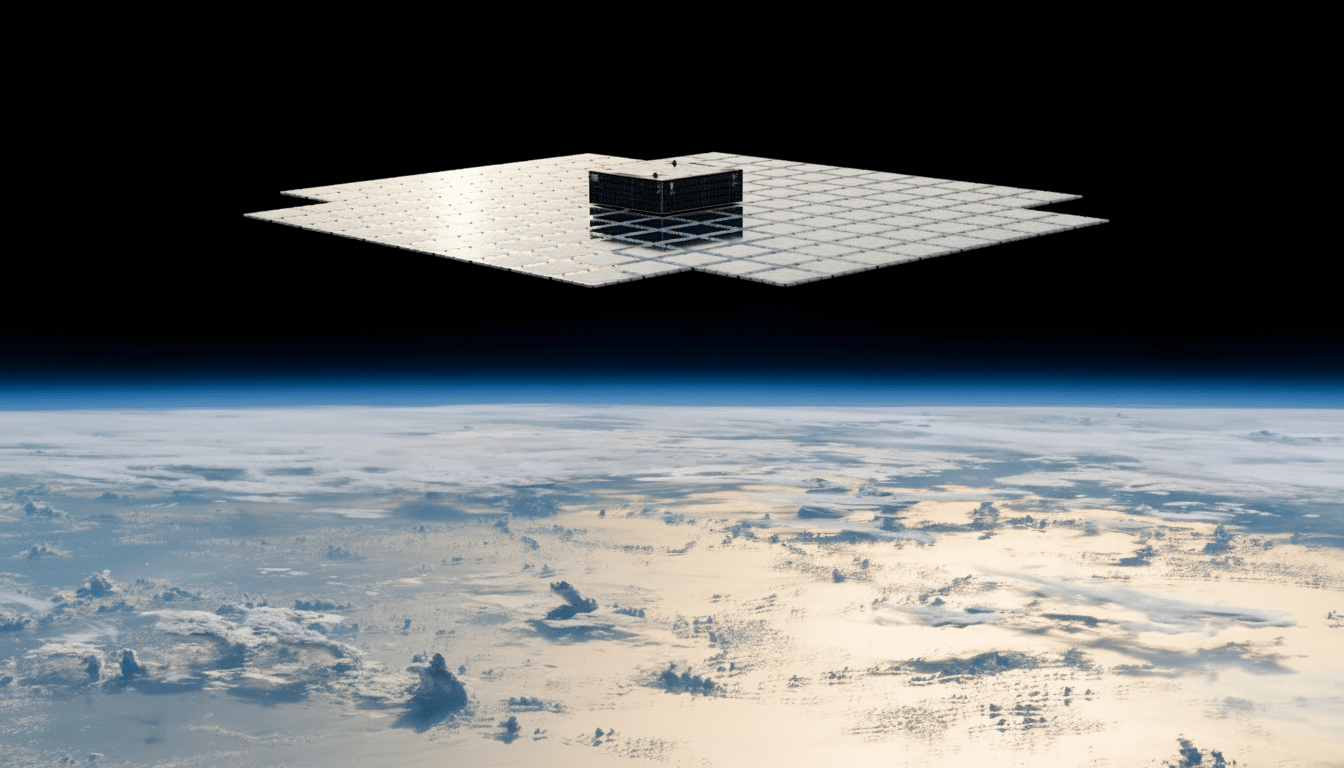

AST’s bet is architectural: instead of trying to cover the sky with lots of small nodes, it uses a handful of huge phased-array satellites to deliver lots of link budget to unmodified smartphones. Its BlueWalker 3 test payload unfurled to some 64 square meters in size, which was one of the reasons the spacecraft became one of the brightest objects in the night sky. The scale decreases the number of spaceships required to provide coverage and handoffs, but it also poses visibility and collision cross-section questions AST says it’s solving through design, propulsion, and end-of-life processes.

The congestion question in LEO

Worries about crowding are not theoretical. The European Space Agency follows tens of thousands of items larger than 10 centimeters and orders of magnitude more smaller debris, and commercial tracking firms report annual growth in the number of conjunction alerts within popular low Earth orbit shells. More satellites means more close approaches to keep track of and more opportunities for human or software errors to snowball into debris-producing events.

Astronomers have sounded the same alarm. The American Astronomical Society and the International Astronomical Union have raised concerns about the effects of satellite streaks on wide-field surveys, like the ones that the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will conduct. SpaceX has tested VisorSat shades, coatings and attitude tweaks to darken Starlink, while AST claims that it is working with the National Science Foundation, the IAU and NASA to minimize the brightness of its next-generation BlueBird satellites. Both companies also highlight operating in lower orbits, so that failed spacecraft can deorbit more quickly naturally.

Regulatory chess match at the F.C.C.

AST’s application is subject to intensive technical review and public comment, a process that allows rivals to challenge safety and interference claims. SpaceX has stated that very large satellites present unique risks; AST maintains that fewer nodes /big plus robust propulsion, automated maneuvering capability, and constant conjunction screening results in fewer hazard. The FCC’s five-year post-mission disposal requirement for LEO satellites is now the arch compliance baseline, and any green light will be pendent on believable deorbit plans and interference coordination under the international (ITU) gangplank.

The market sprint to direct-to-cell

SpaceX has a head start in the make-a-smartphone-from-space race. Millman noted that SpaceX’s direct-to-cell payloads are already enabling texting with a major U.S. carrier and headed in the direction of limited mobile data. The company said this week that it also had agreed to a $17-billion spectrum transaction with EchoStar, including parent of Boost Mobile, that could eventually produce terrestrial-like performance after handsets have the benefit of those airwaves.

AST sides with AT&T and Verizon. Today it has all of five BlueBird satellites in orbit; analysts and the company’s own briefings suggest it will require an order of 45 to 60 for seamless coverage over the United States, and many, many more to serve the world. Executives have laid out a blistering pace for launches, but the proof point in the near term is execution: manufacturing throughput, rideshare availability and the capital to scale.

What to watch next

The central sustainability question is subtle: is the space around Earth better used for (a) thousands of small satellites, each of whose individual brightness is less, or (b) dozens of large platforms, each of which are more visible and have a fatter cross-section for collision? By deploying fewer satellites, there are fewer of them to be the sum of conjudiction opportunities, but each large vehicle becomes more significant. Inquiries will focus on deorbit reliability, autonomous avoidance, tracking accuracy, and optical effects—not just headline constellation sizes.

Look for more cutting filings at the FCC, more test data from the astronomy working groups and a quick fire battle of launches from both players. Whatever the rivalry, the era of direct to cell, will be about orbital stewardship and transparency as much as the indicator bars strafing across a smartphone screen.