NASA’s Artemis II astronauts are poised to become the first humans to directly view vast stretches of the moon that no one has ever seen in sunlight, including the spectacular Mare Orientale basin skimming the far side. The crew’s looping flyby could align orbital timing and lighting in a way that reveals subtle details beyond the reach of past missions, even those that circled the far side during Apollo.

Mission planners say up to 60% of the far-side terrain that has never been seen by human eyes could be illuminated during the pass. That prospect turns a routine navigation milestone into a rare scientific opportunity, with trained observers using both cameras and their own vision to study color tones, brightness, and texture across ancient lunar crust.

Why This Flyby Could Reveal Lunar Firsts

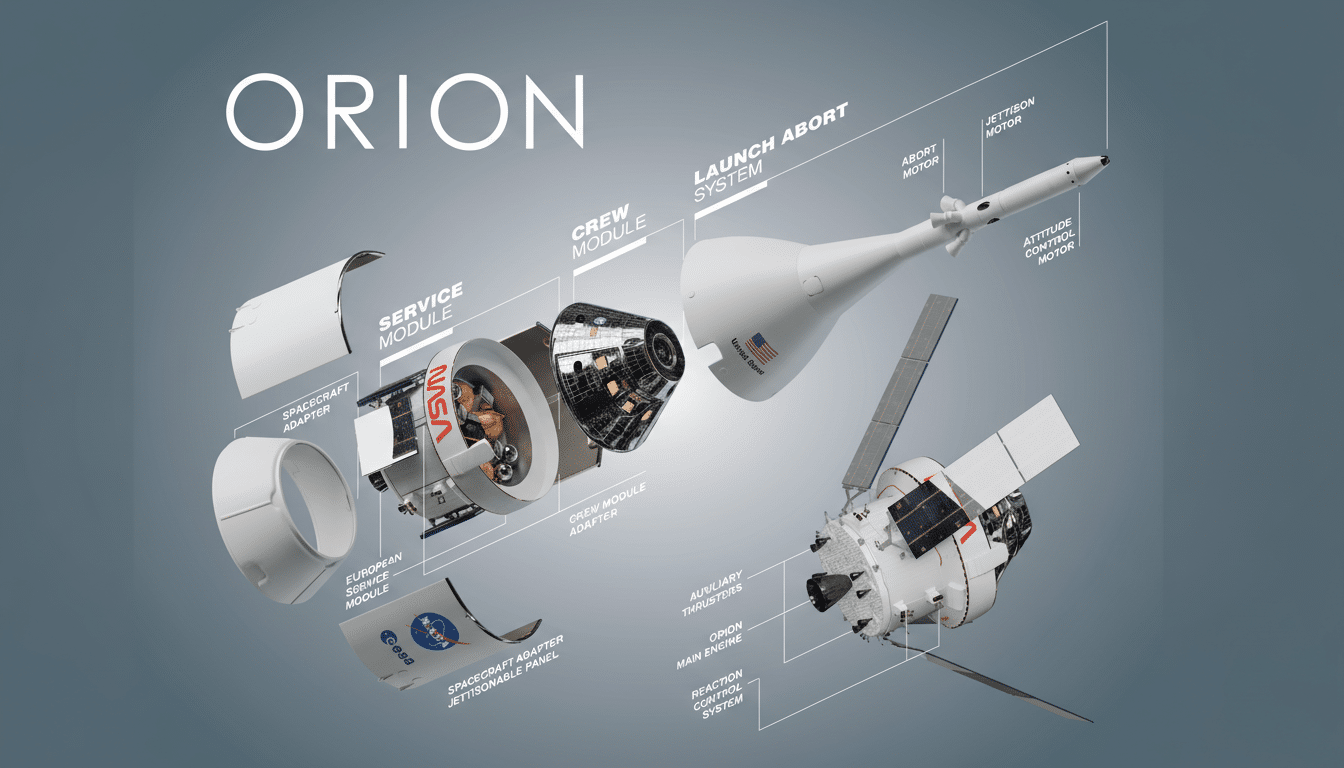

Artemis II follows a free-return trajectory that slings the Orion spacecraft around the moon and back to Earth. Unlike Apollo 8, whose timing emphasized sunlit views of near-side landing zones, the current plan targets a window when the far-side hemisphere is in broad daylight. The difference isn’t altitude or cameras—it’s geometry and timing.

A synchronous dance locks the moon’s rotation to its orbit, keeping one face turned to Earth. That doesn’t mean the far side is dark; it receives the same day-night cycle. The trick is catching those landscapes when Orion is there and the sun is high enough to pull out contrast without flattening features. Artemis flight dynamics teams have tuned the schedule for exactly that.

Targeting Mare Orientale and the Far Side

Among the prime sights is Mare Orientale, a breathtaking multi-ring impact basin nearly 950 kilometers (about 590 miles) across, straddling the western limb where near- and far-side geology meet. Robotic spacecraft from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and other missions have mapped it in exquisite detail, yet no astronaut has ever viewed its mountain rings and lava-flooded interior directly by eye.

Seen obliquely from Earth, Orientale hides most of its structure. From Orion’s vantage, the crew could trace the concentric arcs of the Cordillera and Rook Mountains, inspect the transition from dark volcanic plains to brighter highlands, and spot radial ejecta patterns that hint at impact dynamics. Human vision excels at pattern recognition—especially when the sun angle enhances shadows along crater rims and massifs.

Trained Eyes and Cameras for Far-Side Observations

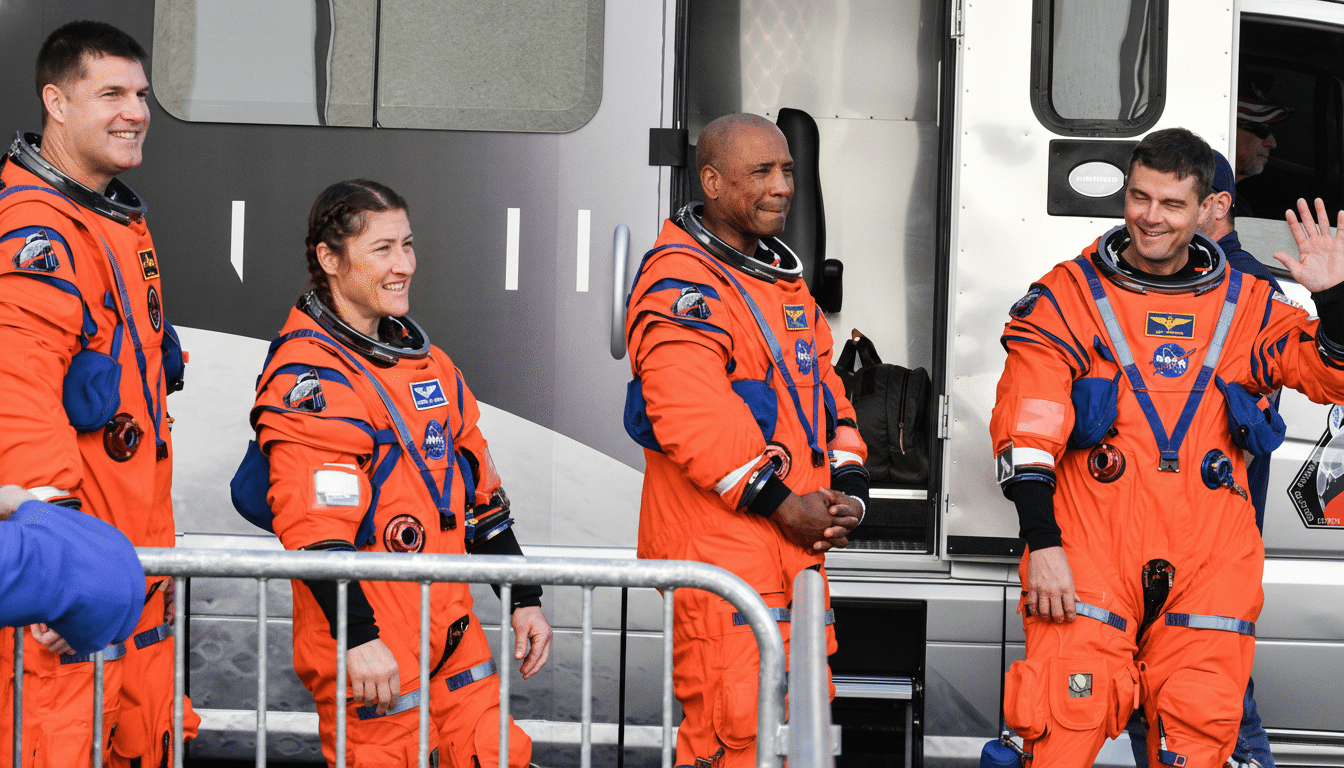

Although Artemis II won’t land, its four-person crew—Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Hammock Koch, and Jeremy Hansen—have sharpened their observational skills with geology refreshers led by NASA science teams and partner experts. The goal is to turn a short window at lunar distance into actionable science.

Plans call for roughly three hours dedicated to far-side observations. Expect a fast cadence: naked-eye scans to capture overall context, instrumented photography for fine detail, and real-time descriptions to flight controllers. Checklists will highlight priority targets, but the crew will also be free to follow their instincts—key to catching transient lighting effects or noteworthy textures the checklists didn’t anticipate.

From Orion, the moon will fill the windows like a basketball held at arm’s length, large enough for the crew to compare subtle albedo shifts—darker mare basalts against brighter anorthositic highlands—and to watch how crater rays fade with age and space weathering.

Why Human Observations Still Matter at the Moon

High-resolution maps from LRO, Japan’s Kaguya, and other orbiters have transformed lunar science, but astronauts can still add value. Human eyes can detect faint color variations, layering, and texture patterns that slip past automated algorithms—especially at oblique sun angles where subtle relief stands out. Those impressions, linked to precise images, help calibrate interpretations of remote-sensing datasets.

The far side preserves a cleaner impact record than the near side, where large basaltic plains masked older scars. That means fresh clues about the solar system’s bombardment history and the age of key terrains. Artemis II observations could also guide where to send future landers—NASA’s Artemis surface missions, international partners, and commercial payloads—by flagging sites with rich stratigraphy or well-exposed ejecta.

Beyond the Flyby: What Comes Next for Artemis

Operating on the far side is hard. The moon itself blocks direct radio links, which is why China placed a relay satellite, Queqiao, beyond the lunar limb to support the Chang’e-4 far-side landing. Artemis II won’t rely on a relay, so some observations will be stored and downlinked when communications resume. Still, what the crew records can inform architectures for future relays, the Lunar Gateway, and surface missions that aim to work in the far-side radio-quiet zone prized by astronomers.

If conditions line up, Artemis II could do more than retrace history—it could expand it. A handful of targeted looks at Orientale and sunlit far-side highlands may reshape maps, refine timelines, and narrow the search for the most scientifically compelling places to explore next. That’s the promise of pairing world-class imagery with human judgment at lunar distance.