I wasn’t alone in bristling when a startup vowed to re-create the missing footage from Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons with generative AI. The idea sounded like a lightning rod for cinephile ire with little cultural upside. But fresh reporting and new guardrails suggest the effort, led by Fable founder Edward Saatchi, is evolving into something more careful and potentially illuminating—if still contentious.

A deep-dive profile by The New Yorker’s Michael Schulman paints a portrait of a team driven more by devotion to Welles than by hype. It also surfaces crucial facts: the project is pursuing rights and estate approvals, consulting bona fide Welles scholars, and acknowledging the steep technical and ethical hurdles ahead. That doesn’t resolve the core dilemma, but it does reframe it.

Why This Lost Film Still Haunts Cinema History

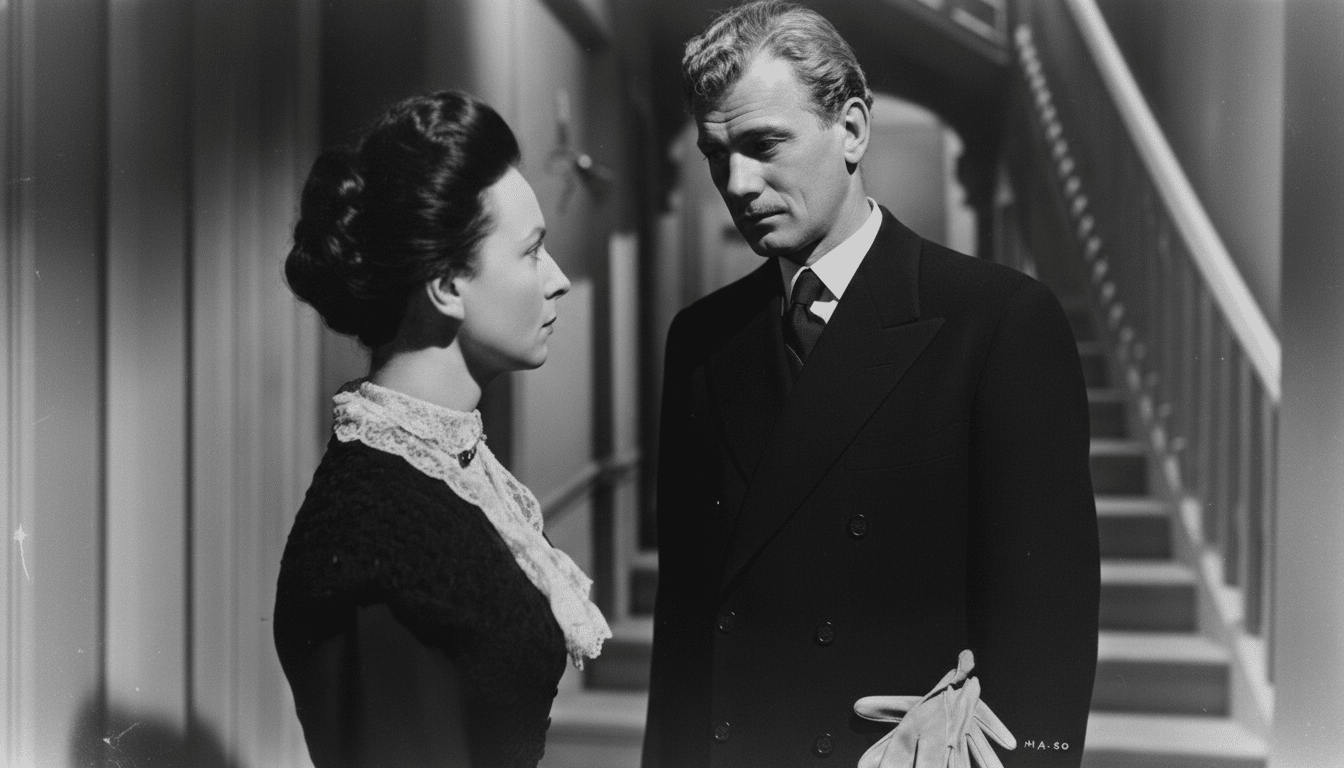

Released in 1942, Ambersons is cinema’s wound that never fully healed. After disastrous test screenings, the studio excised 43 minutes and imposed a jarringly upbeat ending, then reportedly destroyed the cut scenes. Welles would later claim Ambersons was the “much better picture” than Citizen Kane—an assertion that keeps the loss alive in film lore.

The surviving version is widely admired, but it’s also visibly truncated. In an era when archives and restorations routinely yield revelations, the notion of glimpsing even a facsimile of Welles’ intended rhythms and tonal gravity exerts a powerful pull. That temptation is what Saatchi is chasing.

Inside the Fable Plan and Its Evolving Technology

Fable isn’t starting from scratch. The company is collaborating with filmmaker Brian Rose, who previously storyboarded and animated missing sequences using surviving stills, the script, and Welles’ notes. Fable’s twist is to stage scenes in live action and then apply AI-driven face and voice models to approximate the original cast—Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead, Anne Baxter, and others—over contemporary performers.

Early tests reveal the scale of the challenge. Visual artifacts—like a two-headed Cotten in one pass—underscore how brittle these systems can be. More subtly, the models tend to smooth away human complexity; even Fable notes a “happiness bias” that lightens expressions in scenes that should ache with regret.

Then there’s the look. Ambersons was shot by Stanley Cortez, whose sculpted chiaroscuro and deep-focus staging produce a specific mood that off-the-shelf image models don’t natively understand. Matching that grammar requires not only style transfer but lens emulation, period-accurate grain, gate weave, and lighting continuity—techniques closer to high-end VFX than to prompt-and-go generation.

Notably, there’s still no public footage of Fable’s hybrid method. That restraint may be wise; premature clips can cement mistrust. But it also means the project’s promise—respectful speculation versus garish pastiche—remains unproven.

Rights, Ethics, and the Consent Question in AI Filmmaking

Legal and moral clearance will make or break this. Warner Bros. controls film rights, while the Welles estate governs elements of likeness and legacy. Saatchi has acknowledged missteps in outreach but is now courting both. Welles’ daughter, Beatrice Welles, is reportedly skeptical yet open to the team’s respectful posture. Historian and actor Simon Callow, who is completing the fourth volume of his Welles biography, has agreed to advise.

Opposition remains real. Melissa Galt, daughter of Ambersons star Anne Baxter, argues that any AI reconstruction is a substitute truth—and that Baxter, a purist, would have rejected it. That view dovetails with broader concerns from performers about digital replicas. Recent SAG-AFTRA agreements codify consent and compensation rules for AI uses; without clear consent pathways from estates and rightsholders, voice and face cloning is a red line.

Precedents cut both ways. James Earl Jones has licensed his voice for future Darth Vader performances via a licensed synthesis partner, demonstrating a consent-first model. By contrast, controversy erupted when a documentary synthesized Anthony Bourdain’s voice without clear disclosure, showing how audience trust can collapse if provenance isn’t explicit.

What Success Would Actually Look Like for Ambersons

At best, this won’t be a “director’s cut.” The missing footage is gone; what Fable proposes is an interpretive study. Success therefore depends on rigorous labeling, clear onscreen watermarks or title cards, and comprehensive annotations detailing sources—script pages, continuity reports, stills, memos—so viewers understand exactly where invention begins.

Film restoration has long favored transparency. The 2010 restoration of Metropolis integrated newly found Argentine footage while flagging gaps with intertitles. Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old and the audio breakthroughs behind Get Back show how AI can clarify what exists. Inventing what never survived requires an even higher bar for disclosure.

The Stakes for AI in Film Preservation and Trust

There’s a preservation case for exploring this carefully. The Library of Congress estimates that 75% of American silent features are lost. If ethically governed, AI could help contextualize fragments, visualize stage directions, or test editorial hypotheses without claiming historical finality. Done poorly, it blurs authorship, erodes trust, and feeds fears of synthetic culture supplanting the archive.

That’s why this Ambersons effort matters beyond cinephile circles. It will help set norms for consent, disclosures, and aesthetic fidelity. I’m still wary. But with expert advisors, estate dialogues, and humility about what can and can’t be recovered, I’m slightly less mad—and more curious to see whether the team can produce an honest, clearly labeled thought experiment rather than a counterfeit.