A second round of distributed denial-of-service activity has raised the bar on raw internet firepower. Cloudflare says it defended against a DDoS attack that hit 22.2Tbps and 10.6 billion packets per second at the peak, lasting just over two minutes and aimed at one IP address belonging to a European internet infrastructure firm.

The firm says the attack is by the Aisuru botnet and is approximately twice the size of an 11.5Tbps incident seen earlier this month.

- What Set This Attack Apart: Simultaneous Bandwidth and PPS

- Inside the Aisuru Botnet and Its Consumer IoT Footprint

- Why the Numbers Matter for Layer 3/4 DDoS Campaigns

- Collateral Risk and Business Impact from Volumetric Floods

- A Faster Arms Race Against DDoS as Botnets Keep Growing

- What to Watch Next as Aisuru Evolves and Copycats Emerge

Cloudflare says it was able to see and stop the spike, preventing it from having downstream effects on customers.

What Set This Attack Apart: Simultaneous Bandwidth and PPS

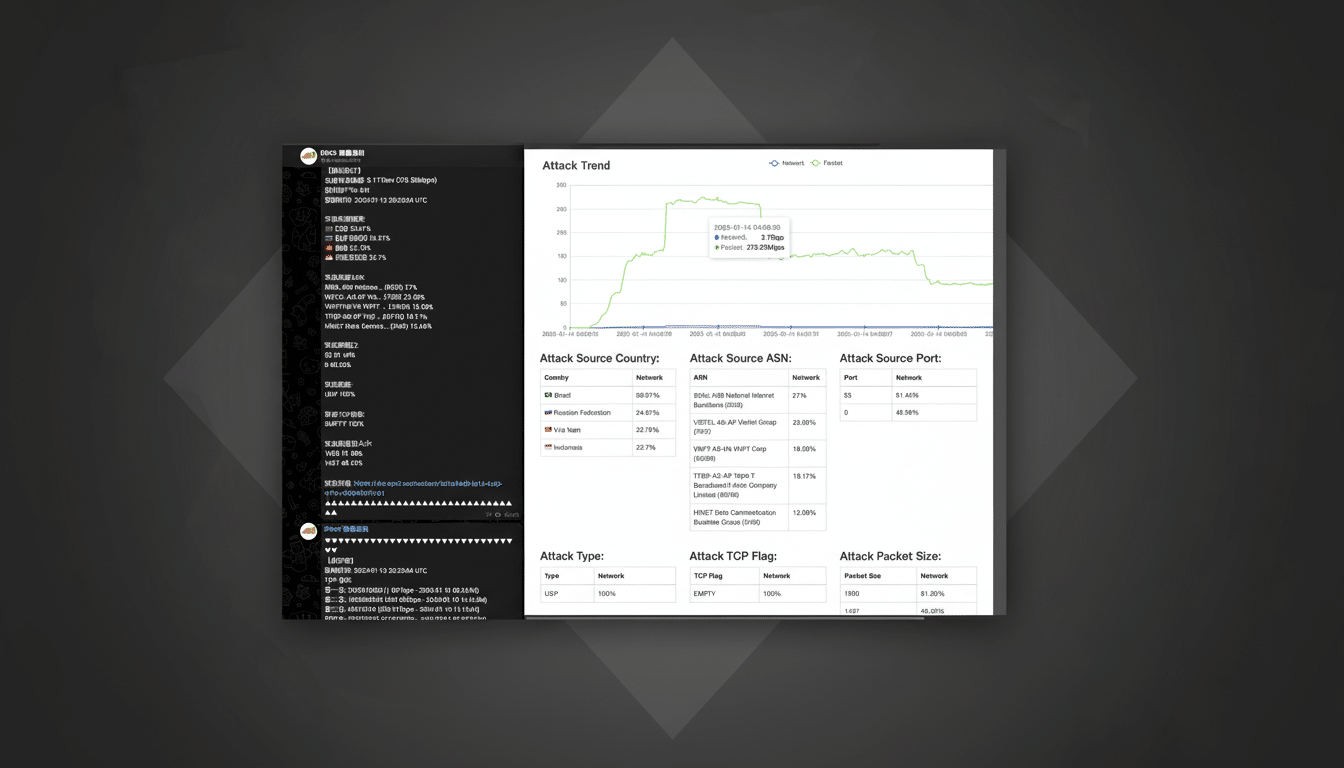

Unprecedented DDoS attacks tend to be heavily skewed to either bandwidth (terabits per second) or packet rate (billions of packets per second). This one pushed both. The 22.2Tbps peak throughput will fill up transit links and peering points, while the 10.6 Bpps is just the kind of packet storm that will bring down stateful devices and overrun routing silicon long before bandwidth limits are reached.

Cloudflare’s telemetry registered traffic from 404,000 unique IPs and observed that the source addresses were not spoofed. That implies a significant number of actually compromised endpoints or abused servers, rather than a reflection-only campaign forging IPs to bounce traffic off broken services.

Inside the Aisuru Botnet and Its Consumer IoT Footprint

Teams within QAX, at what is described on its website as an R&D organization called XLab, have attributed Aisuru to the earlier 11.5Tbps attack and say that they believe the botnet includes roughly 300,000 distinct devices — primarily consumer IoT gear such as insecure home and small-office routers.

The operators reportedly seeded at least some of the footprint by hacking an update server used by router manufacturer Totolink to deploy malware, according to XLab.

Cloudflare’s count of 404,000 participating IPs suggests the presence of additional resources, such as hijacked servers and proxy networks. Brian Krebs, a security journalist, has reported on allegations that the controllers of Aisuru offer access to the botnet through Telegram channels. The culture around these crews often values spectacle — large, high-drama “demolition” blasts — more than money, a temperament that mirrored the short but intense life Cloudflare documented.

Why the Numbers Matter for Layer 3/4 DDoS Campaigns

“Size” of DDoS is not a single measurement. Terabits per second wreak havoc on link capacity and upstream carriers (Layer 3/4 volumetric floods); requests per second pummel application stacks and CDNs (Layer 7). Hundreds of millions of request-per-second Layer 7 events have been reported by hyperscalers in the past few years. Aisuru’s newest shot is simply a Layer 3/4 attack, meant to throttle network paths well before it could ever load any web server.

The short duration matters, too. Most modern botnets use high-intensity “microbursts,” which rotate through targets to avoid blacklists and exploit the interval when traffic is not yet scrubbed. Successful mitigation depends on zero-second detection, automatic routing to scrubbing facilities, and anycast capacity allowing for multi-terabit attacks without congestion.

Collateral Risk and Business Impact from Volumetric Floods

Even when the target can still be reached, volumetric floods can cause collateral damage: airlines using shared transit links, degraded peering sessions, and control-plane load on edge routers. Packets per second at the very high end, like 10.6 Bpps, are particularly brutal to stateful firewalls and load balancers, which can overflow connection tables at millisecond resolutions.

For businesses, the lesson is less about this particular victim than it is about being ready. Cloudflare’s response demonstrates the importance of default-on DDoS protection, pre-provisioned scrubbing, and transparent routing policies to reroute traffic. Advice from agencies such as CISA stresses practiced playbooks, coordination early on with upstream ISPs, and rigid limits placed on uninvited traffic into services that are critical.

A Faster Arms Race Against DDoS as Botnets Keep Growing

Welcome to this installment in our brief series relating advancements in technology to jeopardizing service availability. Industry reporting from key network monitoring firms — such as NETSCOUT and Akamai — has tracked consistent growth in both attack volume and peak throughput, with multi-terabit floods no longer outliers. Insecure-by-default IoT, unpatched edge devices, and DDoS-for-hire services provide a giant swipe card to botnet operators.

Disrupting Aisuru won’t be trivial. Takedowns usually involve the cooperation of device manufacturers, ISP/Telco filtering, patches to the exploited firmware, and legal action against access brokers. If XLab’s assumption about a supply-chain breach at one (not yet identified) router vendor pans out, it shows how an infected update to even a single path can plant tens of thousands across networks within uninvolved businesses and offices.

What to Watch Next as Aisuru Evolves and Copycats Emerge

Key signals include:

- Changes in the number of active nodes Aisuru operates

- Pivots to different target sectors beyond infrastructure and ISPs

- Presence of copycat clusters that reuse its tooling

Also, greater transparency from router makers about firmware integrity and more-invested manufacturers distributing patches with alacrity might make the pool of exploitable devices smaller.

The newest entry not only shows that the ceiling for DDoS throughput continues to climb, but also that automated, globally distributed defenses can stem even the most eye-popping spikes.

The race now is whether defenders can hang on to that edge, even as the botnets grow in size — and those Aisuru numbers suggest the next “record” isn’t far behind.