Sudo serves as the gatekeeper to everyday Linux administration: a better way to give your users superpowers without allowing them to run rampant of the entire system. It’s enabled by default in most of the major distributions, and cloud images preferentially assign direct root logins the role of sudo. Used well, it’s a tool for security’s principle of least privilege; used poorly, it’s a funnel toward trouble.

Security teams from NIST to CIS have long maintained the single most-effective way to reduce risk is to control privilege. Even sudo itself, if you can believe it, isn’t perfect—just ask Baron Samedit (CVE-2021-3156) or the pwfeedback vuln (CVE-2019-18634)—so it’s important to maintain configuration discipline and stay on top of updates. Here are six subtle yet essential changes to sudo that every Linux user should make, as well as one somewhat silly tweak.

- Use visudo—and drop-in files too

- Whitelist real needs, don’t just give ALL

- Blacklist dangerous commands — and shut escape hatches

- Delegate by Group, not User

- Make password prompts easier (but be careful)

- Limit the time sudo will remember you

- Edit root-owned files with sudo -e safely

- Just for fun: sudo insults

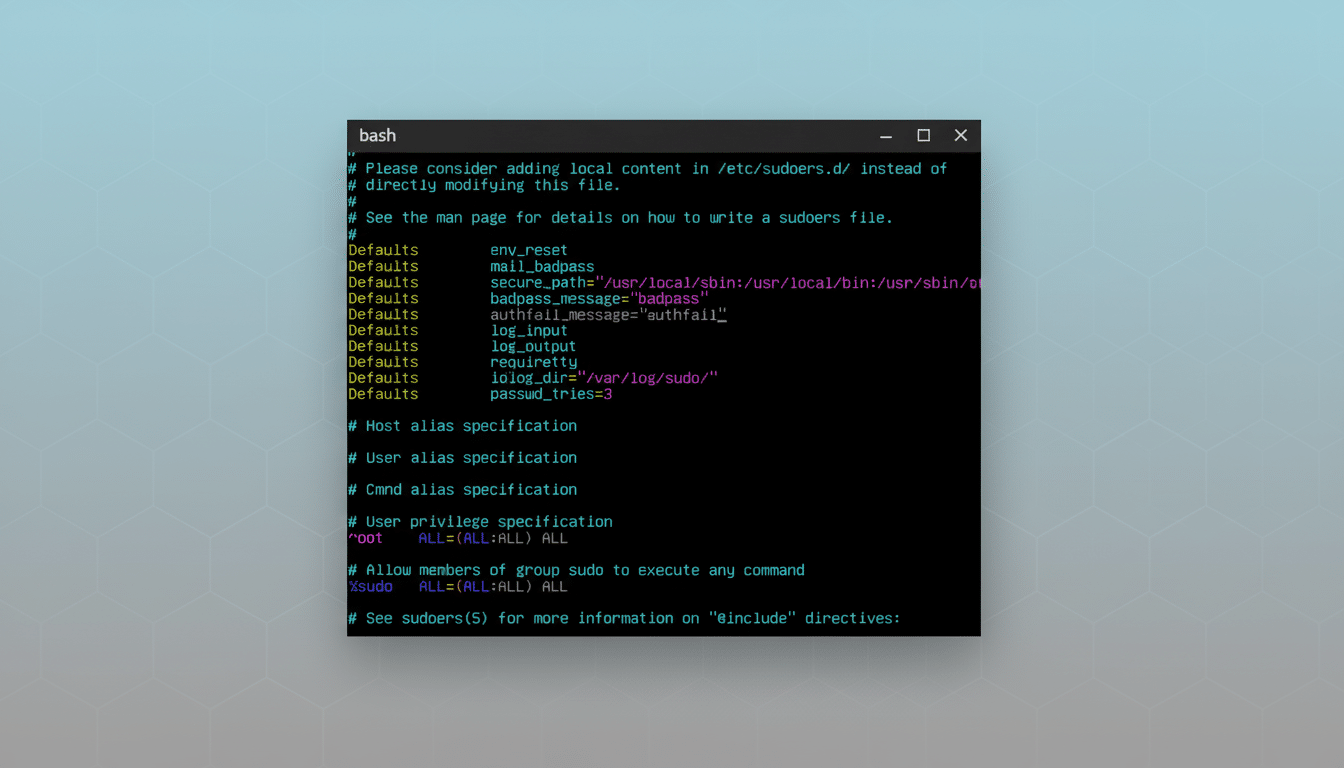

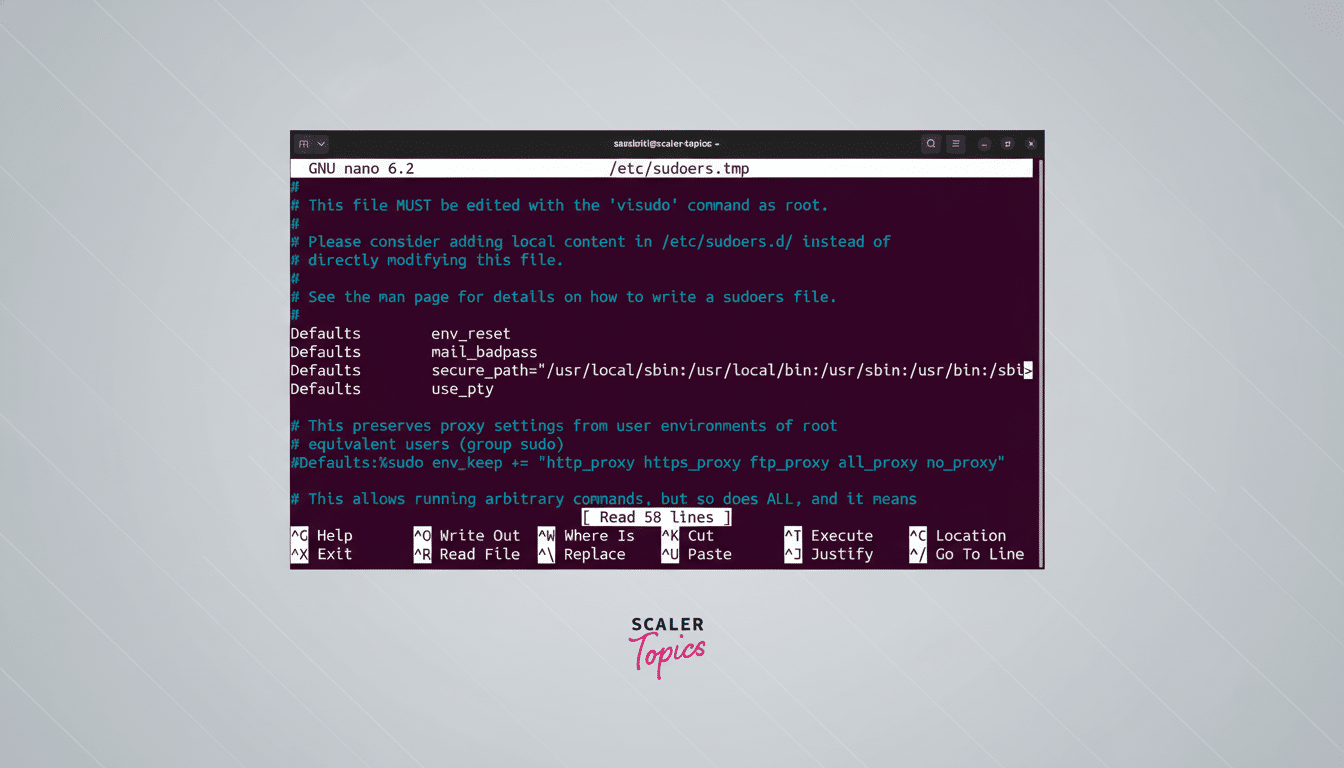

Use visudo—and drop-in files too

Do not use a general-purpose editor to edit sudo’s policy! Instead use visudo.

Visudo runs syntax checks and will refuse to save a broken /etc/sudoers (which could mean no admin access at all). Tip: run “visudo -c” to check without modifying it.

`/etc/sudoers` contains an `#includedir /etc/sudoers on most distros. d”. Simply put custom rules in that directory with “visudo -f /etc/sudoers. d/filename” so that updates don’t stomp on your changes and so that you can version control small, focused policy files.

Whitelist real needs, don’t just give ALL

Simple “USER ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL” is easy—and a boobie trap for the (evildoer) that gets the password for a user account. You should whitelist only the specific commands users require, rather than everything. just to make it readable, use Cmnd_Alias:

Cmnd_Alias PKG_MGMT = /usr/bin/apt, /usr/bin/dpkg

%support ALL=(root) PKG_MGMT

If you have to be able to access directories, finish them with a “/” so that only binaries in the directories are allowed (e.g., “/usr/sbin/”). Explicit command lists are still safer and auditable.

Blacklist dangerous commands — and shut escape hatches

Sudo has the ability to deny certain commands with “! operators, e.g., “! /bin/rm” to stop destructive deletes. That’s helpful, but still not enough: a user who can run an interactive editor or shell could still get around your block by shell escaping.

Add a couple of layers of additional security: set “Defaults secure_path=…” to force a known-good PATH while sudoing, and use the “NOEXEC:” tag to protect against invocations that may fork processes.

Use blacklist rules in combination with narrow whitelists for a defense in depth.

Delegate by Group, not User

Auditors love clean policies. So does future-you. Provide sudo to groups, manage membership independently: “%ops ALL=(root) PKG_MGMT” 2. And when interns leave, or roles change, you are changing group membership once, instead of digging for per-user lines in multiple files.

For small labs or families running a PC, it also halts “privilege creep”—a frequently noted misconfiguration in enterprise incident reports, where overly broad access remains long after anyone needs it.

Make password prompts easier (but be careful)

If you like visual feedback while you’re typing your sudo password, use asterisks “Defaults pwfeedback”. It cuts down on fat-finger errors and streamlines workflow.

Note: the pwfeedback vulnerability (CVE-2019-18634) affected previous sudo releases but only if this option was enabled. Modern distributions have patched it, but double check your sudo version by using “sudo -V” and subscribe to your vendor’s security announcements and the National Vulnerability Database to update systems.

Limit the time sudo will remember you

You have to re-enter your password automatically after a few minutes. Tune that with “Defaults timestamp_timeout=VALUE”. Set it to 0 to force a password every time (good for a shared server), 15 for a reasonably helpful solo-workstation window or, just because, -1 to never let it expire (a bad idea).

Two commands to keep in mind: “sudo -v” renews your ticket without executing a privileged command; “sudo -k” invalidates it right away. Between them, they allow you to tighten or lengthen access right when it’s called for.

Edit root-owned files with sudo -e safely

Break the “sudo nano /etc/whatever” habit. Instead of using r00t just “sudo -e /etc/whatever” (sudoedit). It copies the file to a temp location and writes back atomically, which helps if you have to sudo to edit the file (e.g. ssh while having a miss-configured.ssh/authorized_keys file), because it keeps the original permissions with the copy.

Pair this up with restricted command whitelists and you can make it so users can only sudoedit what their role requires – perfect for on call engineers needing to tweak a single config without having full shell access.

Just for fun: sudo insults

Missed your password? Let sudo rib you with gentle insults by adding “Defaults insults ”. It’s not going to harden your system, although it can make a long day at the terminal a bit, well, softer. If you’d prefer a more polite nudge instead, “Defaults lecture=always” will show a pop-up reminding you to use responsibly.

Bottom line: keep sudo up-to-date, model access on the concept of least privilege, and write policy that you can say in one breath. This is how you cripple a useful weapon into an unworkable one.