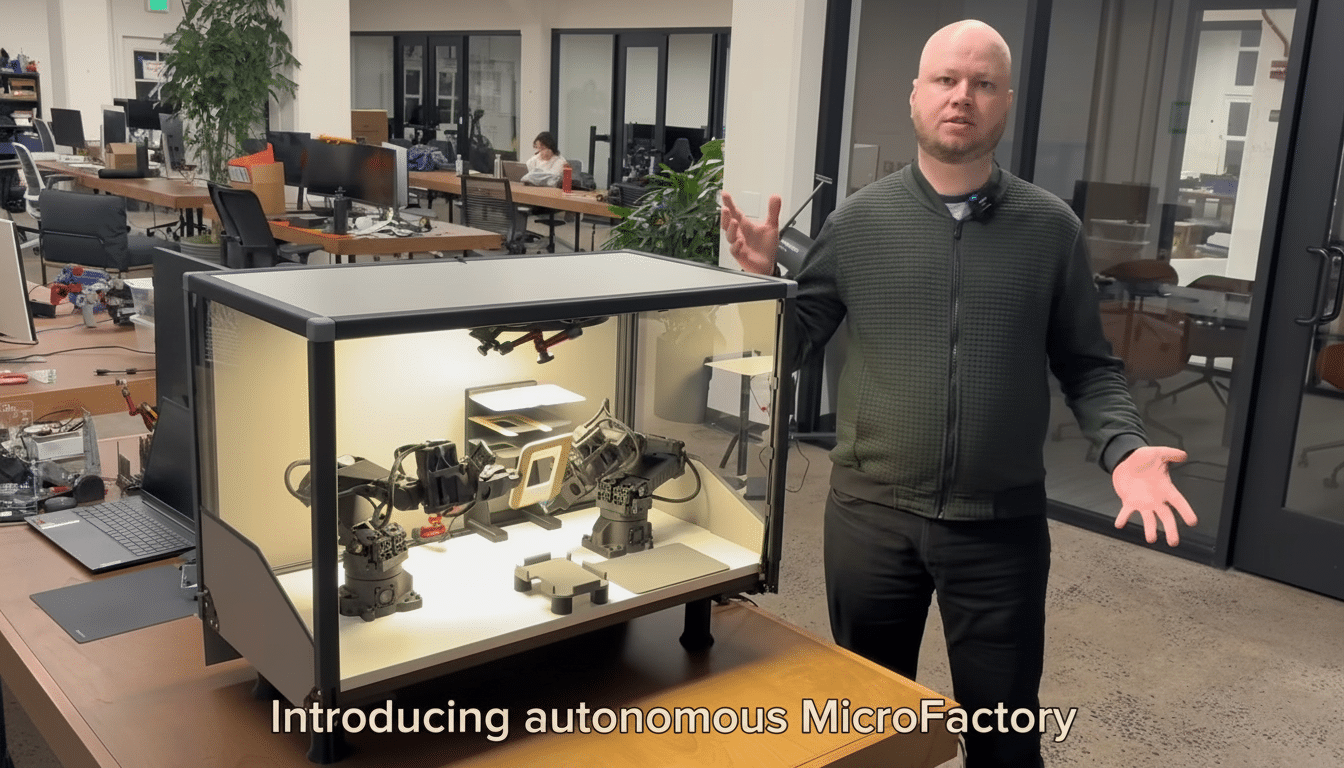

An industrial automation startup in San Francisco, MicroFactory is miniaturizing automation into a clear-walled, dog-crate-like workstation that’s capable of being trained the way you train your family when putting them to work. Called the company’s compact “factory-in-a-box,” it packages two robotic arms with vision and software that learns how to do complex tasks by someone just showing it — aimed squarely at small and midsize manufacturers hungry for precision but not an automation team.

A factory that learns by doing real production tasks

Instead of programming every movement, workers guide the arms through tasks like soldering a connector, routing cables, or placing components onto circuit boards. The system records those actions, refines them using AI, and executes them at high speed. Most workflows can be taught in hours, not days, co-founder Alexander Kulakov says, because the robot is “feeling” the motion path and intent instead of a script or teach-pendant menus.

- A factory that learns by doing real production tasks

- Why small systems can grow large in modern automation

- From lighting gear origins to building learning robots

- Funding, valuation, and the company’s push to ship units

- How this approach fits into today’s robotics landscape

- Key performance metrics that will matter to buyers

The enclosed station is compact enough to sit on a benchtop yet capable of doing work that typically requires a dedicated cell: pick-and-place, adhesive dispensing, inspection, and rework. MicroFactory hopes that the combination of having arms, safety, and cameras all packed into one unit means deployment is like installing a lab instrument — rather than commissioning a traditional robot cell.

Why small systems can grow large in modern automation

Few factories resemble flashy automotive lines. Global robot installations, in a blow to the métier of Walter Scott’s dreams, were increasing at record rates, but adoption trends continued to favor large companies, according to the International Federation of Robotics. For small suppliers there is no shortage of obstacles, such as cost of integration, programming time, and the unpredictability of manufacturing. A benchtop unit that can be taught via demonstration directly addresses those pain points: minimal footprint, fast changeover, and no need for on-staff robotics experts.

There’s precedent for this shift. In cobotics, companies such as Universal Robots brought hand-guided teaching for basic skills into the mainstream. MicroFactory extends that concept to multi-step, high-precision processes with a fully enclosed station. It’s a practical gambit that echoes NIST and academic lab guidance: kinesthetic teaching and imitation learning can rapidly shrink the span from concept to automated cycle, particularly for high-mix operations.

From lighting gear origins to building learning robots

Kulakov and co-founder Viktor Petrenko ran bitLighter, which produced portable lighting gear for photographers. Teaching up new hires on the delicate assembly work was a slow and uneven process, an experience that embedded the core insight of MicroFactory: If people can teach people by showing them how to do something, why can’t they teach robots in the same way? His original rope-a-dope plan came when he saw all the advancements in computer vision and policy learning over the past couple of years that this was possible, so he pieced together a working prototype in about five months.

Early demand suggests it has struck a chord beyond electronics. It has hundreds of preorders, company reps claim, from PCB assembly to the comically specific, such as preparing snails for escargot — precisely the sort of repetitive, low-volume task that traditional automation has a hard time justifying but which is much helped by consistent handling and traceability.

Funding, valuation, and the company’s push to ship units

MicroFactory, backed by a group of Hugging Face executives and investor-entrepreneur Naval Ravikant, recently closed a $1.5 million pre-seed round at a valuation of $30 million post-money. The funding is intended to be used for developing the prototype into a commercial product and for scaling production. The team is aiming for around 1,000 units in the first year of production — about three per day — growing to a 10x output yearly as supply chains and assembly lines mature.

The immediate roadmap is centered on shipping, customer support, and small AI improvements. That means broadening the model’s skill set, improving its visual inspection accuracy, and tightening repeatability — crucial for processes where misplacement by even a fraction of a millimeter can result in downstream failure.

How this approach fits into today’s robotics landscape

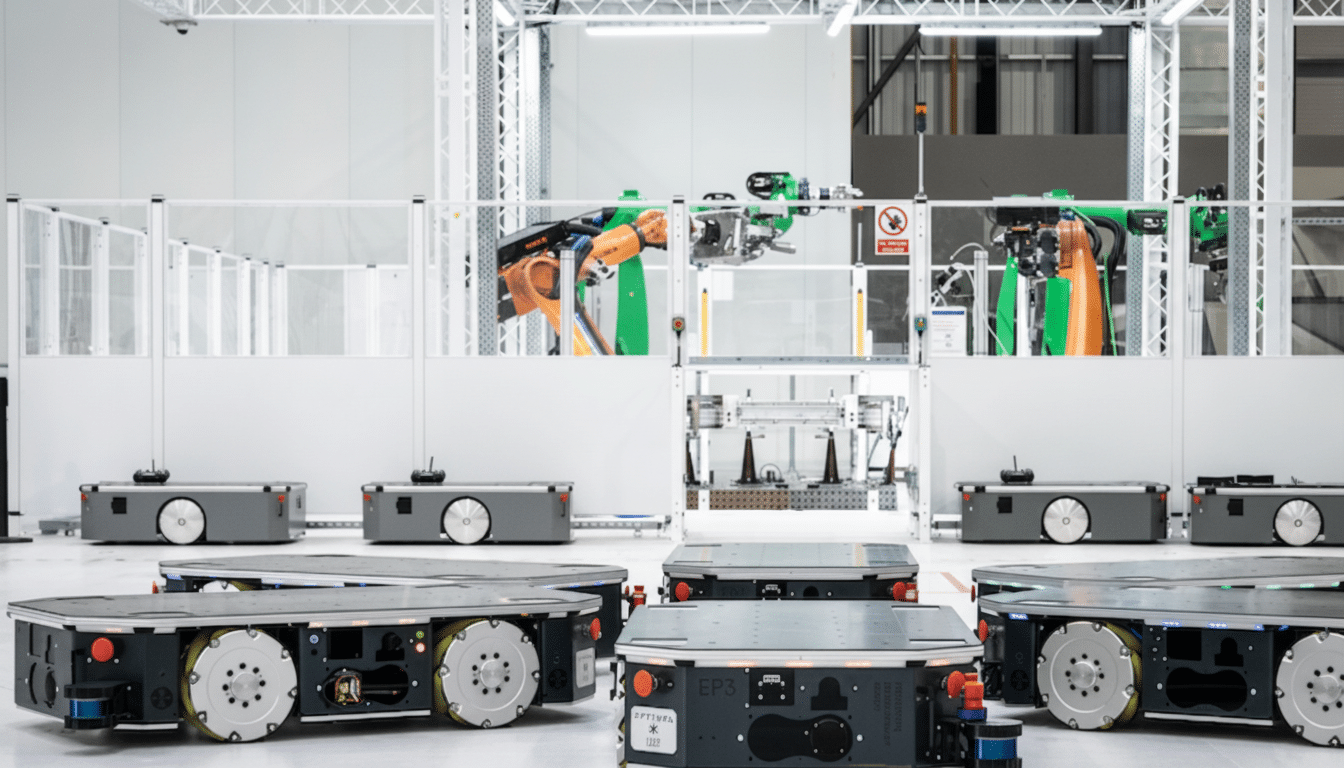

While the headlines are fed by humanoids and full-factory autonomy, most companies automate a machine or line at a time. MicroFactory is less in competition with giant integrators than it is do-it-yourself cells and contract assemblers. Its differentiator is packaging, a turnkey box that can be taught by the process engineer in the morning and run production in the afternoon. That lowers integration friction — often the stealth majority of automation cost, according to analysts at McKinsey and others.

And from a technical perspective, the approach depends on imitation learning, vision-based pose estimation, and policy refinement — tools that have been advancing at a rapid clip due to research from labs associated with institutions like Stanford or Berkeley as well as commercial advances in foundation models for manipulation.

The problem is reliability at the edge: keeping cycle times and yield on track in drafty, messy real-world work cells. Success is likely to depend on guardrails such as force control (to modify the robot’s pressure in response to a new task), anomaly detection, and fast retraining when parts or fixtures change.

Key performance metrics that will matter to buyers

For the same reasons a hybrid is not actually ever 50 mpg, buyers will ask the same questions they do of any robot: What’s the true setup time? At how many units per hour, and at what defect rate? How fast can we switch SKUs? Can I manage more than one station? If MicroFactory can deliver sub-day deployment, repeatable quality, and quick retraining, it could shrink payback periods to quarters instead of years — particularly in electronics labs and contract manufacturing where labor is hard to find and variability is high.

The upshot: by making automation feel like collaborating with a colleague instead of programming a machine, MicroFactory is betting that the smallest factory on the floor can unlock the most cavernous expanse of unmet demand. If the company strikes its shipping goals and the devices work as promised, the benchtop could be the next front for industrial robotics.