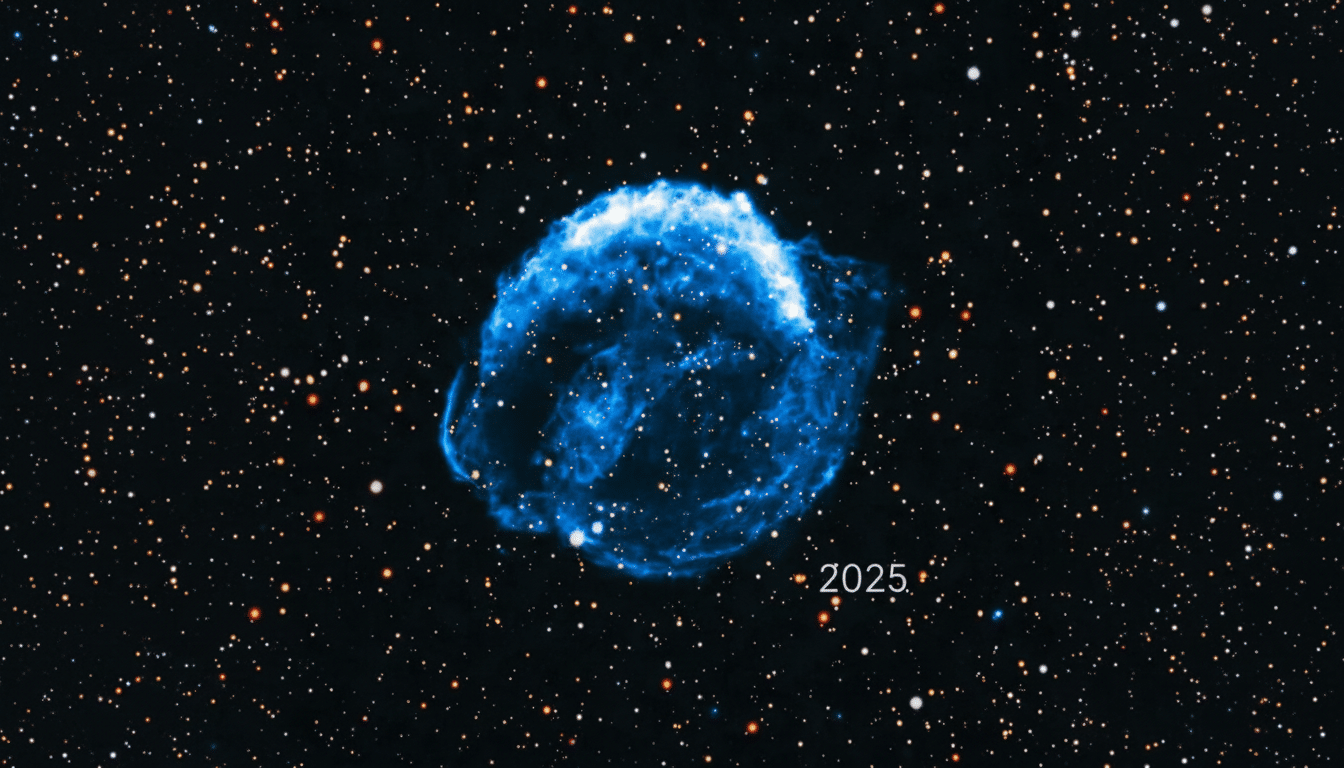

Stitching together a remarkable 25-year time-lapse of the aftermath of an actual exploding star, astronomers have glimpsed a superheated shock front racing across space and ramming into clumps of material in the vicinity. Recorded by the NASA Chandra X-ray Observatory, the new video provides a glimpse at the expanding shell of the Kepler Supernova Remnant, a 400-year-old vestige located roughly 17,000 light-years away, and features rare direct measurements detailing how one of these stellar explosions expands in a messy real-world environment.

Scientists note the sequence is Chandra’s longest viewing of any X-ray movie so far, and it also serves as a physics lab for understanding how Type Ia supernovas operate—essential knowledge for improving the “standard candles” by which we have mapped out our place in the cosmos.

A Quarter-Century in X-rays Revealed by Chandra Data

Starting with observations in 2000, astronomers watched a blast wave expand from the supernova, cutting bright, filamentary threads where it smashes into gas and dust and heats it to tens of millions of degrees.

The shock front had traveled about half a light-year — approximately 3 trillion miles — over the span of the observations, providing “a rare ruler” with which to measure an evolving aftermath of a particular supernova rather than by some theoretical model.

Motion isn’t uniform across the remnant’s rim. In some directions, the jet-zapped shock rushes ahead at nearly 14 million miles per hour; in others it creeps along at roughly 4 million mph. That difference is the first big clue that the explosion is encountering areas of vastly varying density, acting less like a snow globe plowing through some patches of powder and packed ice than as a perfect sphere soaring through emptiness.

A Non-uniform Shockwave Maps Density Across the Remnant

Kepler’s remnant is the remains of a Type Ia supernova, which probably occurred when an old white dwarf star in a binary system accumulated enough material from its companion to cause a runaway thermonuclear explosion.

Long before the explosion, gas billowed into space and sculpted an uneven terrain. The new measurements effectively map that fossil record: Speeding motion traces thinner regions; slower arcs trace into denser, preexisting clumps.

Fascinatingly, scientists find that the overall shell is still fairly spherical despite such density contrasts. If so, then the seemingly asymmetric “bubble” might not be lopsided stoichiometry in the explosion at all, but motion of the explosion’s center through a mixed medium — subtle dynamics you can chart only by taking precision measurements over decades.

Why the Details of Type Ia Supernovas Matter

Type Ia supernovas form the basis of some of the most important measurements in contemporary cosmology, like those that led to the revelation that cosmic expansion is speeding up. Their maximum illumination can be calibrated, and distances in the range of a few percent can be measured, provided conditions are well known. But no two environments are identical, and local variations have the power to stir up observed brightness and color in ways that can grow into distance estimates.

And by measuring how Kepler’s shock decelerates or accelerates as it plows through varying densities, the new study aids in calibrating how circumstellar material modulates the light that reaches our eyes. Those, in turn, contribute to better models for teams at institutions like the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Space Telescope Science Institute to use in shrinking systematics from supernova-based distance ladders.

How Astronomers Made the 25-Year X-ray Time-lapse

Half-arcsecond resolution is Chandra’s sharp vision, enabling observations of changes around the remnant’s edge on scales of arcseconds from months to years on a dozen lines-of-sight.

The team stitched together multiple observational epochs from 2000 to 2025, matching and comparing the X-ray rims in order to determine proper motion and estimate velocities. That 25-year window represents about 6 percent of the remnant’s estimated remaining lifetime, an impressive fraction for a single instrument observing a single object.

The Kepler Supernova Remnant is one such historical marker, the most recent supernova explosion observed to occur in our Milky Way galaxy and believed to have been witnessed by early astronomers as a new star in the constellation Ophiuchus. It has since been X-rayed using modern X-ray telescopes (XMM-Newton) that enabled detailed comparison with several centuries-old observations. Multiwavelength perspectives — along with optical surveys led by teams deploying instruments such as Pan-STARRS and radio studies from the Very Large Array — provide context of the surrounding gas and dust that shape the blast’s evolution.

What’s Next for X-ray Eyes and Future Supernova Studies

Chandra continues to provide one-of-a-kind stable long-baseline data, which would be desirable—an experiment difficult and expensive to practically replicate.

Nevertheless, astronomers are looking ahead to the next generation of high-resolution X-ray missions. That’s the kind of precision observation that would be extended by something like the proposed AXIS satellite, which could deliver new time-lapses charting how supernova remnants cool, crash into each other, and mix with the interstellar medium over human timescales.

For the moment, this new Kepler video provides a special treat: a front-row seat to a thermonuclear blast in real time with actual quantities of how much and how fast the shock wave spreads through space. It’s a stunning image and is also an observational linchpin for some of the most pressing challenges in our understanding of cosmology.